Deconstructing Tilburg: the Heilig Hartkerk

Like many Dutch cities, Tilburg prides itself on its churches. It even mentions the church towers in its unofficial anthem: “k Zie zo gèren al die toorens, mee d’r kruise fier in top”, which translates as ‘I love seeing all these towers, with their spiers proudly in the air’.

The demolition of the Heilig Hartkerk

Sadly, some of the greater churches that used to adorn the city skyline, are now gone. It was not the bombs of the Second World War that were guilty of their disappearance, nor were it fires, or other misfortunes. The churches were intentionally demolished by the inhabitants of the city themselves. A decision many people now regret. (Van Hoek, 2007) Was it a flurry of bewilderment? Or did something more deliberate, and possibly even malicious, happen when these massive stone buildings met their expiration date?

In this essay, I will identify the different factors that induced the ravaging of the architectural heritage of the city of Tilburg in the 1970’s. For the purpose of this research, I will use the Heilig Hartkerk, which loosely translates as ‘Church of the Holy Heart’, as a case study. This church has been referred to as ‘The most beautiful demolished church in Tilburg’ (Sparidans, 2015), and came in 14th place in a national contest titled ‘most beautiful demolished church’. (Heilig Hartkerk, n.d.)

Willingness to make great sacrifices

When my grandfather passed away in 1974, my family organized a funeral service in the Heilig Hartkerk, which was commonly known as the ‘Noordhoekse kerk’, because it was the most important structure within the ‘Noordhoek’, a distinct region of the city. "The church was the heart of the Noordhoek", my father explained. "It was the place where you were baptized, you had your first holy communion, you got married. It was the place where we held our funerals."

For the inhabitants of the Noordhoek, the church had always been a stable factor, a community home, something to be proud of. They had witnessed the rapid expansion of the city, her growing prosperity as a result of the flourishing textile industry and her increasing desire for innovation and modernization. Tilburg had transformed from a seemingly unimportant collection of poor rural communities into a city of interest. And the Heilig Hartkerk was part of the tangible evidence.

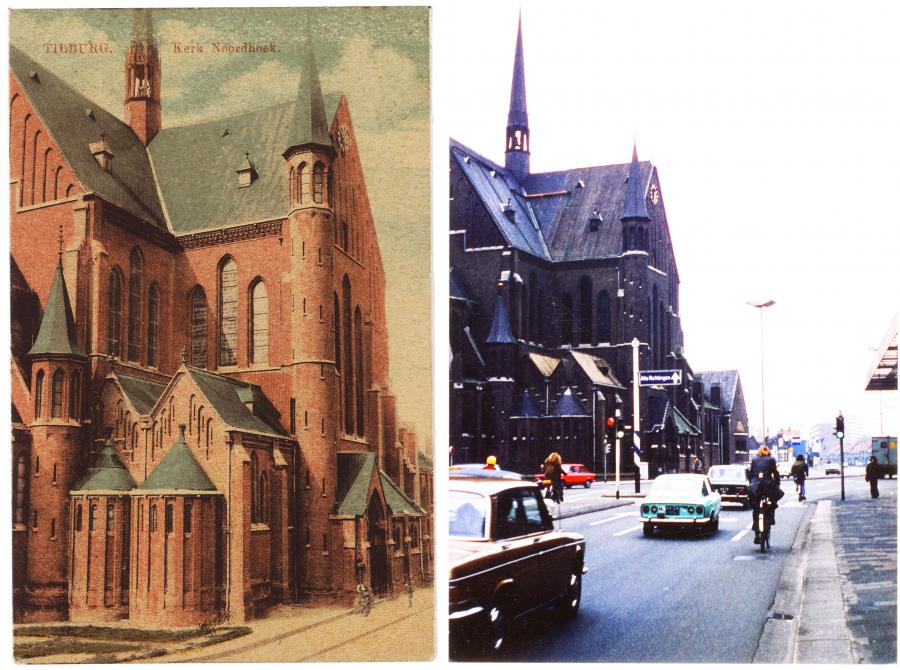

On the left: A postcard showing the backside of the church in 1910, provided by the Regionaal Archief Tilburg. On the right: A picture by Alex Beekmans showing the backside of the church in 1975 when the demolition had just started.

But only a few weeks after my grandfather’s burial, the local church government published a threatening and urgent message in the local newspaper: “The commission for Church Spatial Planning in Tilburg has advised to close the church in the near future”, the publication states. “Do you think we should follow their advice? If not, are you prepared to continuously make great sacrifices to help us carry the burdens?” (Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, 1974).

Following this request, the parish organized a well attended meeting. According to the local newspaper, during this meeting, many passionate pleas were made by the parishioners, trying to convince the church government to renounce their plans. But in the end, these pleas appeared to have had no effect.

In January 1975 the church was closed. Only a few days later, the municipality signed its demolition permit. The official reason? The rapidly rising maintenance costs, its awkward location in relation to the cityring, and the declining number of church visitors.

The not-so-Cuypers church

The Heilig-Hartkerk was designed by Pierre Cuypers between 1894 and 1896, and completed in 1898. Cuypers, who passed away in 1921, is still one of the best known Dutch architects, famous for designing buildings like Amsterdam Central Station and Het Rijksmuseum. Unfortunately for Cuypers, and building pastor Dr. van Zinnincq-Bergmann, the Noordhoek-parishioners were unable to collect enough money to stick to the original design. The grand tower that Cuypers’ had envisioned to accompany the church, was never build.

In 1931, the local church government commissioned Cuypers’ son Joseph Cuypers to create a new design for a church tower. This design met the same fate as the first design; the church could not afford it. They did however, manage to collect enough money to make some other additions to the building; a “colossal new entrance” (Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, 1974) was created. Also, some concrete reinforcements were added.

Parishioners could drive their cars right up to the new structure that was designed by Joseph Cuypers, Pierre Cuypers' son.

When the parishioners met in 1974 to discuss the future of their church, the missing tower and the 20th century additions were an important part of their conversation. Just a few weeks earlier, the national organisation for the conservation of monuments had listed 136 churches as important material heritage. These churches “could not be demolished without a special permit”, and the national government would fund necessary restaurations (Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, 1974).

Unfortunately, the Heilig Hartkerk was not added to the list for two reasons: The fact that the original design by Pierre Cuypers was never executed properly, and the fact that his son had made some additions that had “interfered with the possibility for a future completion of the original design” (Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, 1974). According to the local newspaper, the parishioners requested the national organisation for the conservation of monuments to reconsider their decision. Unfortunately, the document in which their request was recorded, if this document ever existed, was lost.

The arguments that were presented in 1974 by the national organisation for the conservation of monuments would probably still apply today. In a study by E.C.M. Ruijgrok, the importance of authenticity is addressed, defining authenticity as something that is closely connected to ‘originality’, meaning that whenever the original building is incomplete, or unoriginal materials were used to adapt certain parts of the structure, the building would become less authentic, and might not be ‘cultural heritage’ (Ruijgrok, 2006). Following this line of reasoning, the incomplete design and the additions made by Cuypers’ son caused the Heilig Hartkerk to be an ‘unauthentic building’, and therefore no cultural heritage.

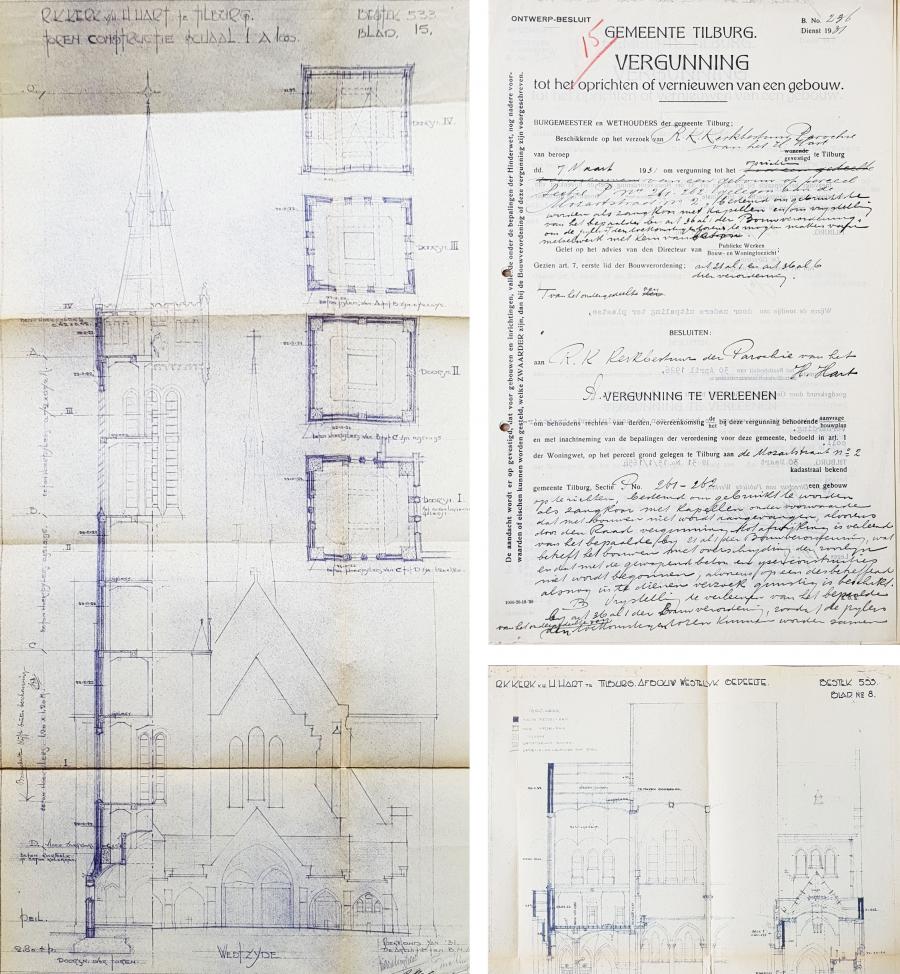

On the left: A drawing of the new church by Joseph Cuypers. On the right: Another drawing of the changes that would be made to the church building, and a permit from the local government, allowing the changes to be made.

Disliking Cuypers’ lack of authenticity and abundance of Catholicism

The relationship between Cuypers and the national organisation for the conservation of monuments has always been somewhat peculiar. After becoming actively involved in the preservation and restoration of old buildings and pieces of art around 1850, the Dutch government established the ‘Commissie der Koninklijke Akademie van Wetenschappen, tot het opsporen, het behoud en het bekendmaken van overblijfsels der Vaderlandsche Kunst en Beschaving uit vroeger tijden’. (De Mayer et al., 1999) The commission never managed to achieve any actual results, because of a lack of governmental and public interest in the care for monuments.

Still, the existence of the commission led to the establishment of another organisation: the ‘College van Rijksadviseurs voor de Monumenten van Geschiedenis en Kunst’, which was heavily dominated by Pierre Cuypers and Victor de Stuers, both members of the organisation. After a few years, a large part of the organisation collapsed, due to what was described as “internal tensions” (De Mayer et al., 1999, p. 5). A more precise cause for these tensions was never mentioned, yet we can assume that the personal background of both Cuypers and De Stuers played a significant role. Both were born in Limburg and identified as ‘Catholic’. And even though Catholicism had been legalised in 1848, many people, including the royal family, felt that the Netherlands should remain a Protestant country. Cuypers and De Stuers tendency to prefer building styles that were considered to be ‘Catholic’ was not appreciated by many government officials.

The collapse of the organisation had a surprising effect: Cuypers and De Stuers managed to appropriate even more influence when it came to the restoration and construction of important buildings. Cuypers had the ability to advice the government to restore or construct buildings in a certain manner, and in many cases, his own company carried out the recommended work. This conflict of interest was criticized by younger architects, who believed Cuypers’ refabrications of medieval churches and castles were inauthentic and tasteless. Even after Cuypers’ influence had decreased and the famous architect passed away, people criticized and disliked the work he had done (De Mayer et al., 1999).

Group portrait that was made on Cuypers' 90th birthday in Roermond

Monumental elitism vs. the public opinion

When it came to the average inhabitant of the province of Noord-Brabant, the disliking of monumental buildings went beyond the disapproval of Pierre Cuypers. In the local newspaper, J. Willems, who was the chairman of a subdivision of the national organisation for the conservation of monuments, argued that most citizens considered the care for old buildings to be ‘elitist’. This observation is acknowledged by other officials. The mayor of Heusden, a historic village in the province of Noord-Brabant, states that: “Until now, a monument was seen by most people as a rather useless stone mass that was perishing, with just a few hobbyists thinking it should be preserved.” (Wensveen, 1974).

In Who needs experts? Counter-mapping Cultural Heritage (Schofield, 2004) the relationship between the management of cultural heritage and the public opinion about cultural heritage is discussed. According to Schofield, it is important to notice that any cultural heritage manager must listen to the public opinion, since the public has entrusted him or her with the protection of their cultural heritage. But on the other hand, he argues that a cultural heritage manager must always act on behalf of the cultural heritage he or she is trying to protect against other interests of society.

It is not inconceivable to think that there is a connection between the distribution of attention, and the perception that the care for monuments is ‘elitist’.

Therefore, he argues that cultural heritage experts should always be willing to start a dialogue with the public. He notes that, in this dialogue, it is important to pay attention to the notion that scholars and well-established citizens are often more capable to participate in this dialogue than other members of society. If we link this notion to the case of the Heilig Hartkerk, it might be interesting to note that it are indeed mainly scholars, experts, government officials and church officials that voice their opinion about the future of the Heilig Hartkerk in the public sphere (Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, 1974).

It is not inconceivable to think that there is a connection between the distribution of attention, and the perception that the care for monuments is ‘elitist’. It might be hard to prove that the care for monuments is not elitist, when the only opinion that is thoroughly recorded, is the opinion of the local elite. The importance of a dialogue in which every stakeholder gets involved, is also underlined by the Council of the European Union (The Council of the European Union, 2014).

Lapidaire was called ‘executioner’ by the local carnival association. In this banner, a frequently used sentence is featured: "Executioner, keep it short."

"Brute, keep it short"

The local newspaper reports might have created the image that the average inhabitant of the city was not interested in the preservation of the church, or in some extreme cases, even disapproved of the care for monuments. But according to some secondary sources, this was very much not the case. Frans Kense, who authored multiple books on the history of Tilburg, describes how the demolition of the church was heavily protested by the general public. According to him, even the local carnival association got involved in the protests by hanging a big banner on the building across the central train station, on which Lapidaire, who was the pastor of the Heilig Hartkerk at that time, was called ‘brute’ (Kense, 2008). Kense claims in his article that these protests were extensively reported upon by the local newspaper in 1974 and 1975.

Unfortunately, none of the reports Kense describes can be found on the pages of Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, which was the most important local newspaper at that time. On which platforms these protests were discussed, and how many people were reached, is also not mentioned in the local archives. Therefore, it is almost impossible to determine what the magnitude of the resistance was.

However, it is important to note that Kense’s claims are being supported by a small amount of photographic evidence and other secondary sources, stating that: “A revolutionary mood prevailed in the late 60s and early 70s”, and, “Mayor Becht demolished large parts of the city without involving the general public. Something was festering in the city.” (Het Regionaal Archief Tilburg, 2016). Both sources provide plenty of reasons to believe that ‘the average Tilburger’ did have an opinion about the closure and the demolition of the church, but that its voice just received far less attention than the opinions of the clergy, government officials, and some scholars that were involved.

One important primary source remains; At an undetermined moment in 1974, the ‘Actiegroep voor het behoud van de Noordhoekse kerk te Tilburg’, which translates as ‘Action committee for the preservation of the Noordhoekse church in Tilburg’, was founded. The group’s only goal was to prevent the demolition from happening.

In the official city archives, only three sources about the group’s activities continue to exist. The oldest and most comprehensive source is a formal letter, written on the 9th of January 1975, in which the group provides the municipality with 9 counterarguments, requesting it to retain from signing a demolition permit until the 1st of july 1975.

What seems odd, is the fact that the first official letter produced by this group, was written after the church closure, which might be considered a remarkably late moment in the process. Looking at the first sentence of the letter, it appears that the members of the group share this opinion, and are attempting to provide an explanation for their tardy response: “Although there has been talk about this for some time, the decision to close and sell the Noordhoekse church has been made quite suddenly.” (Merks, Janssen, Panis, Koster, & Mijland, 1975, p.1)

An official reply by the municipality and the church government was either lost or never recorded, but a short version of it was used in a newspaper article about the action committee: “Mr. A.J.M. Poelman, counselor of the inner city church government, and member of the committee for the restructuring of Tilburg-Goirle parishes, points out that the closure of the church has been prepared for a long time.” (Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, 1975) This response might be interpreted to mean that the church government has the opinion that it is too late to change their plans at this stage, and that the parishioners should have taken action earlier, as the church asked them to do during the meeting in March 1974.

In the letter, the members of the action committee also ask the municipality to, if they are unwilling to look for other possible destinations for the building, please start the demolition of the building quickly, because they would hate to see their old church building to be vandalised. In the local newspaper, as a response to the response of Poelman, they repeat this request in a less courteous manner: “Brute, keep it short.” (Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, 1975)

The four page letter that was written by the action committee. [Source: Collectie Regionaal Archief Tilburg]

Church buildings won’t feed the poor

In contrast to the municipality and the national organisation for the conservation of monuments, the Catholic church was confidently proclaiming that it was going to pay as much attention to the needs and the views of the general public as possible. In a ‘church renewal plan’ that was formulated in 1974, the local clergy made some wellintended points that might have triggered the events that led to the demolition of the Heilig Hartkerk: “Small spaces, provided they do not cost money. Church closure without the need for replacement space. No money spending on buildings, but on people.” (Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, 1974, p.2). The statement appears to be in line with a new vision that was adopted by the Vatican in 1974: “The church should pay more attention to the needs of its parishioners.” (Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, 1974). This vision was heavily supported by the Dutch cardinal Alfrink.

In 1974, Tilburg was the poorest city of the country with the highest unemployment rate (Het Regionaal Archief Tilburg, 2016). On top of that, many inhabitants of the city stopped attending the Holy Mass. According to the local newspaper, in 1967, over 63 percent of the public went to church regularly, in 1974, that number had shrunk to little over 35 percent (Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, 1974). Due to its shrinking parish, the Heilig Hartkerk was unable to cover its regular costs, reporting a shortage of 20.000 gulden.

A restoration, which would have been necessary to save the church building, would cost over 300.000 gulden (Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, 1975), a sum of money that the impoverished and shrinking community would probably not have been able to come up with. Therefore, the decision to close the church because of the rapidly rising maintenance costs might have not just been a selfish decision of a church that was not willing to spend money on yet another church building, but also a decision to protect the poor parishioners from heavy financial burdens.

This picture was made right before the demolishment of the church started. Its awkward location in relation to the important city infrastructure is visible.

Who owns the church? Parishes as juridic persons

The question remains whether the local church government actually had the right to close the Heilig Hartkerk. If we look at the Code of Canon Law (The Roman Catholic Church, 1983), the answer to that question might very well be “no”. According to canon law, every parish is a so called ‘juridic person’, which means that the parish, and therefore all parishioners, have certain rights and duties.

Some of these rights and duties pivot upon the concept of ownership. In many cases, the parishioners are considered to be ‘the owners’ of certain parts of their parish’ property, as long as the property was acquired legitimately. What ‘legitimacy’ means within the context of canon law, remains vague. However, there is no reason to suspect that the Heilig Hartkerk was acquired by the parish in an illegitimate way, and the money that was needed to build the church in the first place was probably collected by the parishioners themselves. Therefore, the parishioners might have had the right to overrule the church government’s decision.

On the other hand, it is important to note that canon law only functions within the limits of civil law. Even though canon law appears to favour the parishioners’ case, civil law does not necessarily have to ("PART I – GENERAL PRINCIPLES", 2016). On top of that, the money that the parishioners collected in order to build their church, might be legally interpreted as ‘donations’. In many cases, the giving of a donation means that the ownership of a certain thing is transferred from one person or organisation to another person or organisation, meaning that the person who provided the donation gives up his ownership-rights, and therefore, the right to influence the future of his or her donation (Vitug, 2006).

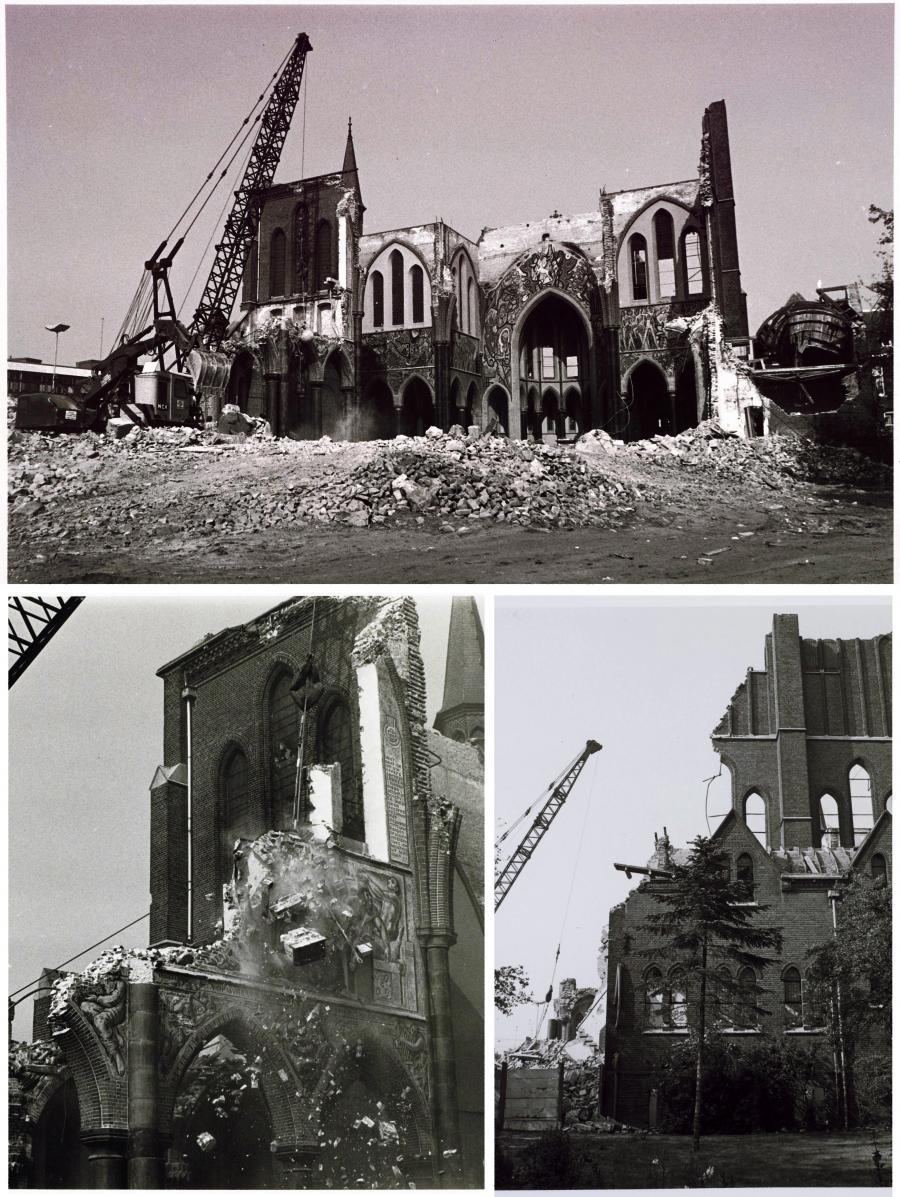

Pictures of the Heilig Hartkerk's demolition.

The importance of a neighborhood ‘home’; social capital and cultural capital

According to the Council of the European Union “cultural heritage plays an important role in creating and enhancing social capital” (The Council of the European Union, 2014, p. 2). Cultural heritage can create stronger communities, enhance the quality of life, and provide a community with a sense of belonging. In the case of the Heilig Hartkerk, this notion can still be observed in practice when looking at the online platforms where people flock together to share memories, displaying their affection for the lost church building. (Sparidans, 2015)

Even my own father, who was an adolescent when the demolition took place, recollects how the members of the local women’s choir congregated in the street next to the church, crying while it was being demolished, proclaiming that they had lost their ‘community home’.

In Heritage: Management, Interpretation, Identity (2003), a relevant point about the concept of ‘local identity’ is made: “Even the acquisition of cultural capital can be seen as a means of providing identity to a particular group. Unfortunately, the designation, conservation and interpretation of much heritage simultaneously makes another group feel less important, less welcome and less secure.” (Howard, 2003, p. 147) Following this line of thinking, it’s not unreasonable to believe that the multiple rejections by the national organisation for the conservation of monuments and the fact that both the municipality and the local church seemed to be unwilling to put in much of an effort to save the church building, inescapably inducing the loss of the Heilig Hartkerk, caused the local community to feel unimportant and unappreciated.

According to Howard, the strength of a local identity is determined by the distinct heritage and features the local community possesses in relation to the distinct features other communities and locations have acquired. For the people living in the Noordhoek, this distinct feature was the Heilig Hartkerk, which they proudly called the ‘Noordhoekse kerk’. So when the church was lost, the community not only lost a large part of its social and cultural capital, but also a large part of its local identity.

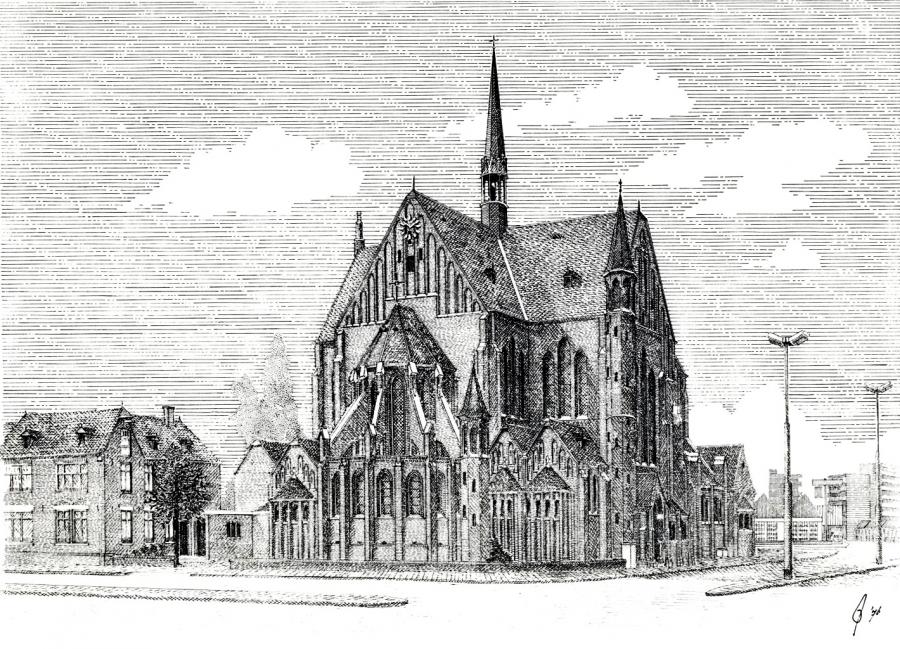

A drawing my father (Alex Beekmans) created in 1976 for the women who cried while the church was being demolished.

Changing perceptions: The builder, the brute and the demolisher

Who gets blamed for the demolition in casual conversations? Nowadays, many people point their finger towards a man they call ‘Cees de Sloper’, which translates as ‘Cees the demolisher’. Cees de Sloper’s actual name was Cees Becht, who was the city mayor between 1957 and 1975. According to local tradition, he encouraged and enabled the demolishment of many historical buildings in the center of Tilburg, which is the motivation behind his current nickname (Geerts, 2009; Regionaal Archief Tilburg, 2011; Joachems, 2016). But in 1975, when Cees Becht retired as mayor of the city, people commemorated him in an entirely different way, calling him: ‘Becht the Builder’.

Interestingly, the perception of the involvement of the mayor on the development of the city has undergone a complete U-turn within the last decades. Cees Becht once was celebrated for modernizing the city and building new homes, but now his work is openly condemned: “For me personally, he has destroyed a lot of the things that I loved, and that feeling of loss becomes stronger with every day that I grow older.” (De Beer, 2010).

In 1975, not Cees de Sloper, but local pastor Lapidaire was at the center of attention. As mentioned before in this essay, the local carnival association created a poster of Lapidaire, on which he was depicted as the culprit for the destruction of the church, and was called ‘brute’. The banner features the text: “Brute, keep it short.”

Interestingly, the exact same sentence was also used in the news article in which the inescapable demolition of the church was announced. In this article, the context of the exclamation had been entirely different: “Pastor Lapidaire, who is charged with the emotional care in the neighbourhood, says, in response to the emotions that live among his parishioners: ‘Brute, keep it short’.” (Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, 1975). It is unclear who Lapidaire is appealing to when he uses the word ‘brute’, but it is definitely not himself. Just as was the case for mayor Becht, the perception of pastor Lapidair, has changed drastically. Within a very short amount of time, Lapidaire went from calling somebody else a ‘brute’, to becoming a ‘brute’ himself.

Two pictures to compare the gasthuisring in 1910 with its view on the Heilig Hartkerk to the way the gasthuisring is looking today. [Source: left: Collectie Regionaal Archief Tilburg. Right: Inge Beekmans]

The broader perspective

So, how is it possible that a building that was so important to so many people was so easily demolished? The Heilig Hartkerk and the city of Tilburg were facing huge challenges in the 70s. Rising unemployment, poverty, dilapidation and secularization forced the local church government and the municipality to make some incredibly difficult decisions. Therefore, from their perspective, the demolishment of the Heilig Hartkerk was probably understandable and the only possible outcome.

If the parish had decided to carry out the costly restoration while its parishioners were living in poverty, it might have provoked irritation. A solution that would satisfy everybody, most likely did not exist. On top of that, in this case, it was unclear which organization had the greatest responsibility, and could be expected to bear the biggest burdens; the national organisation for the conservation of monuments, the municipality, or the local church government? This lack of a sense of ownership resulted in a situation in which the organizations that had the knowledge and practical opportunities to save the church building, appeared to be indifferent concerning its future.

Regarding the care for our cultural heritage, many improvements have already been made over the last few decades (Brown, 2011). Still, once a building is lost, it can never be retrieved. Therefore, we can never be to careful when it comes to the preservation of our cultural heritage. And sadly, recent events provide reasons to believe that we are still not being careful enough.

In 2017, the Sacramentskerk in Tilburg was partially demolished, only its facade and tower remain. The local community protested to save the church building for many years, but the church government decided to close the church anyway (Werkgroep Monumentale Kunst / Erfgoedvereniging Heemschut, 2017). Where the church choir and nave once were, now lies a bare piece of land. In the future, it will be used to build new homes. Tilburg has a long history of demolitions, just like many other Dutch cities. The Heilig Hartkerk was not the first church that had to go, and the Sacramentskerk won’t be the last.

To further improve the process of decision making, I would recommend the national organisation for the conservation of monuments to invest even more time in the establishment of a well balanced dialogue with every stakeholder. Communities need to be coached and helped to participate in this dialogue just as actively and effectively as officials, experts and more well-established citizen.

Also, I would recommend a more flexible attitude towards the definition of 'cultural heritage' and 'authenticity', and towards the selection of buildings and communities that deserve a cultural heritage manager's help. For the national organisation for the conservation of monuments, the Heilig Hartkerk was not worth the trouble. But for its parishioners, it was, and as Schofield argues: heritage managers are in service of the public, which means that if the public wants to preserve something, heritage managers should provide them with a reasonable amount of support. For the Heilig Hartkerk, this support did not necessarily need to be 'financial support', but could also have consisted of advice and assistance during their search for a new destination for the church building, and their correspondance and negotiations with the municipality.

For future research, it might be interesting to analyse the discourses surrounding the care for monuments. In the case of the Heilig Hartkerk, it is not unreasonable to think that a number of discourses might have influenced the decisions that were made. The notions that certain buildings are inauthentic, the care for monuments is elitist and modernization needs to be persued whatever the cost, are just some examples of discourses that might have had more influence on the demolition of the church than practicalities, like overdue maintenance and empty pews.

If we are able to pinpoint the influence that certain discourses and temporary convictions might have on decisions that have long-term implications, we might be able to prevent some of the things that we later regret. Also, more knowledge about this particular topic might help organizations and experts to change or invert the existing convictions and discourses, to ensure that as few people as possible will ever know the feeling of losing their community home.

Picture of the interior of the Heilig Hartkerk in Tilburg.

References

Bowitz, E., & Ibenholt, K. (2009). Economic impacts of cultural heritage - Research and perspectives. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 10, 1-8. Geraadpleegd van https://edubb.uvt.nl/bbcswebdav/pid-1666175-dt-content-rid-5895143_1/cou...

Brown, G. B. (2011). The Care of Ancient Monuments: An Account of Legislative and Other Measures Adopted in European Countries for Protecting Ancient Monuments, Objects and Scenes of Natural Beauty, and for Preserving the Aspect of Historical Cities. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

De Beer, G. (2010, 7 oktober). 2 gedachten over “Bestuur van Tilburg: Mr. Cees Becht (1910-1982)” [Blogreactie].

De Mayer, J., Bergmans, A., Denslagen, W., Stynen, H., Van Leeuwen, W., & Verpoest, L. (1999). Negentiende-eeuwse restauratiepraktijk en actuele monumentenzorg. Leuven, België: Leuven University Press.

Geerts, J. (2009, 8 november). Bestuur van Tilburg: Mr. Cees Becht (1910-1982). Geraadpleegd van https://www.tilburgers.nl/bestuur-van-tilburg-mr-cees-becht-1910-1982/#c...

Heilig Hartkerk. (z.d.). Geraadpleegd van http://www.mooistegeslooptekerk.nl/kerken/heilig-hartkerk/

Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden. (1974, 6 maart). "Kerk wel of niet sluiten?". Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, p. -.

Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden. (1974, 21 oktober). Noordhoek 1 januari dicht. Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, p. 2.

Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden. (1974, 12 februari). Spoedvergadering Pastoraal Beraad. Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, p. 2.

Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden. (1974). "Kerk moet meer luisteren naar wat de gelovigen van haar vragen". Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, p. -.

Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden. (1974, 10 mei). "Breek oude kerken niet zo maar af". Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, p. -.

Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden. (1974). "Te veel monumenten gaan nog verloren". Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, p. -.

Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden. (1974, 20 februari). Einde aan sloopwoede; CRM plaatst 136 kerken op monumentenlijst. Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, p. -.

Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden. (1974, 21 oktober). Excentrisch, te groot, restauratie onbetaalbaar - Noordhoek 1 januari dicht. Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, p. -.

Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden. (1974, 12 oktober). Monumentenzorg, wat kopen we er eigenlijk voor? Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, p. -.

Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden. (1974, 10 september). Kerkbezoek loopt niet verder terug. Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, p. -.

Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden. (1975, 10 januari). Uitstel gevraagd van sloop kerk Noordhoek. Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, p. -.

Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden. (1975, 18 januari). Noordhoekkerk wordt binnenkort gesloopt. Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, p. -.

Het Regionaal Archief Tilburg. (2016, 12 november). Lezing over de Tilburgse muurkrant

Howard, P. (2003). Heritage: Management, Interpretation, Identity. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: A&C Black.

Joachems, W. J. (2016, 2 april). 'Cees de Sloper' burgemeester in Soerabaja en Tilburg: de man van de ringbanen.

Kense, F. (2008, 21 augustus). NOORDHOEKSE KERK; VAN PROTEST TOT PUIN.

Merks, K. J. C., Janssen, Panis, Koster, C., & Mijland, J. H. W. (1975, 9 januari). Het kerkgebouw met tuin kadastraal bekend gemeente Tilburg sectie P.5819, groot 27,99 are, gelegen aan de Noordhoekring hoek Spoorlaan, Hart van Brabantlaan en Acaciastraat.. Geraadpleegd van -

PART I – GENERAL PRINCIPLES. (2016).

Regionaal Archief Tilburg. (2011, 26 september). Cees-de-Sloper, houdoe en bedankt !

Ruijgrok, E. C. M. (2006). The three economic values of cultural heritage: a case study in the Netherlands. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 7, 206-213.

Schofield, J. (2004). Who needs experts? Counter-mapping Cultural Heritage. Farnham, United Kingdom: Ashgate Publishing.

Sparidans, L. (2015, 29 november). DE MOOISTE GESLOOPTE KERK VAN TILBURG.

The Council of the European Union. (2014). Conclusions on cultural heritage as a strategic resource for a sustainable Europe.

The Roman Catholic Church. (1983). 1983 CODE OF CANON LAW.

Van Hoek, P. (2007, 6 april). MET DANK AAN DE TILBURGERS.

Vitug, J. C. (2006). Property, ownership, and its modifications. Manila, Philippines: Rex Bookstore.

Wensveen, H. (z.d.). Monumentenzin van Brabander houdt niet over. Het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden, p. -.

Werkgroep Monumentale Kunst / Erfgoedvereniging Heemschut. (2017, 23 november). Sacramentskerk heeft weer toekomst.