Identity crisis: the confusion of being Chinese Indonesian

From time to time, you might experience a quarter-life, a midlife or even an existential crisis, but what if I told you that identity crisis troubles Chinese Indonesians their whole life? Chinese Indonesians partake in both Indonesian and Chinese culture, but to what extent are they either “Chinese” or “Indonesian”? Identity is made up of far more than one's nationality or ethnicity, but being born into two different cultural identities, Chinese Indonesians residing both in Indonesia and in China struggle to feel a sense of belonging towards a particular nationality.

The origins of the Chinese Indonesian

The Chinese migrated to Indonesia long before Indonesia’s independence. The first wave of migration dates all the way back to the early 15th century, when the Chinese expected to achieve a better standard of living in this new land. Indonesians knew how to make a living mainly through trade, mining and agriculture and worked mainly on the north coast of Java; so, when the Dutch arrived, it was of immense help to them to form a simple alliance with the Chinese settlers. By utilising the Chinese settlers as craftsmen, their knowledge and familiarity with the area helped make Batavia - now known as Jakarta - the metropolis it is today.

In the years of settling in a land of strangers, the initial group of Chinese migrants broke up into smaller groups. This inevitable change occurred mainly due to interracial marriages between Chinese settlers and mainland Indonesians, where the Chinese settlers usually opted to follow the Indonesian customs and converted to Islam, the main religion in Indonesia.

Chinese Indonesian, two different identities

Following Indonesia’s independence, Chinese Indonesians (called Orang Keturunan Tionghoa in Bahasa Indonesia or 印度尼西亚华人 in Mandarin) were again divided into groups; some accepted Indonesian citizenship and some chose not to. This diversification expanded to what is referred to as superdiversity, i.e. the “diversification of diversity”, a concept introduced by Steven Vertovec, to describe phenomena of migration and multiculturalism within a community. This multi-faceted dimension of multiculturalism does not only refer to nationality and origin, but also to differences in social and economic characteristics.

“Chinese Indonesians are not a homogeneous group. They are divided by culture, political orientations, economic background, and citizenship.” (Suryadinata, 2008). This increase in the number of new small groups nationally connected to one another resulted in a heightened confusion regarding what Chinese Indonesians' "true identity" is.

They are received apprehensively on both sides, for no one appears completely convinced that they clearly belong to one of these countries, let alone both.

Although Chinese regulations rightfully regarded Chinese Indonesians as citizens of China, their allegiances to China are a controversial topic. Even after centuries of residing and forming family lines in Indonesia, the liberty to choose between having Indonesian or Chinese citizenship challenges Chinese Indonesians' senses of loyalty towards both countries. They are received apprehensively on both sides, for no one appears completely convinced that they belong clearly to one of these countries, let alone to both.

The public stigma

At present, the term "Chinese Indonesian" is used to refer to anyone of Chinese origin or descent living in Indonesia for a major part of their life. The conception of this term appears to be very broad, but it is no good when it comes to curbing the public stigma surrounding it. “Are you really Indonesian?”, “You don't look Indonesian” and “Do you speak Chinese?” are just some of the questions Chinese Indonesians have to get used to.

To the vast majority of the public, it isn’t right to look Chinese and not speak the language, but it is also not right to be a citizen of a particular country, in this case Indonesia, without looking like its mainland citizens. People all around the world are aware of what Chinese people look like. No matter where they go, people of Chinese origin will automatically be judged to be from China. Thus, saying "we are not from China" or "we don't speak Chinese" is bound to cause confusion or even disapproval since the assumption is shuttered. "Looking Chinese" does not always entail being from China or speaking a variety of Chinese. Similarly, it is worth asking, is it necessary to look a certain way to be considered a member of a nation? Is it logical that Chinese Indonesians are not considered Indonesian even though they were born and raised in that country?

The term "Chinese Indonesian" was born without the people it describes having the liberty to accept or reject it as an identity label; that was never given as an option. When we have a certain identity, we can assume that we possess particular identity traits, but unless others also see us as possessing those traits, it turns out that we do not, in effect, have them. Consequently, having two countries named side by side in one’s identity label as is the case with Chinese Indonesians may not be the best idea after all, since it leads to confusion regarding which nation they rightfully belong to.

A significant impact of superdiversity is the formation of new patterns of inequality and injustice towards subcultures, which is observable also in the case of Chinese Indonesians. New social contexts and polycentric complexity emerge as a result of superdiversity. Subcultures might then arise due to a common fate experienced by their members, stemming from having to face the same problems (Becker, 1963).

There seems to be a certain degree to which Chinese Indonesians are allowed to act as either an “Indonesian” or a “Chinese” person in both countries.

Within each Chinese Indonesian subculture, members take part in both Chinese and Indonesian cultural practices to varying degrees (e.g., some participate in more Chinese customs than others), but each subculture does not operate without criticism from the mainstream culture. There seems to be a certain degree to which Chinese Indonesians are allowed to act as either an “Indonesian” or a “Chinese” person in both countries.

In Indonesia, Chinese Indonesians are generally seen to be members of the higher economic and social class. This stigma relating to Chinese Indonesian’s economic and social statuses supports Vertovec’s statement that “[i]mmigration status is not just a crucial factor in determining an individual’s relation to the state, its resources and legal system, the labour market and other structures. It is an important catalyst in the formation of social capital and a potential barrier to the formation of cross-cutting socio-economic and ethnic ties” (Vertovec, 2007, p. 1040).

Through niched businesses, talent and new forms of cosmopolitanism, migration and superdiversity can change the economic and social standing of a particular group of people. The first Chinese settlers went to Indonesia seeking a better life there. But they eventually grew their different varieties of industries into a core of their own, producing maximum yield with a stronger economy, clustered in a few states, much like a trait of core-like processes (Wallerstein, 2004). Although the Chinese Indonesian community may seem like a core in one aspect (with specialities such as trade and agriculture), it is impossible to be a core in every area, rendering some areas peripheries or semi-peripheries.

Re-gaining their “lost” roots

As a result of not being seen as a “real” Chinese or Indonesian, Chinese Indonesians attempt to reinforce their “roots” through practices in their daily lives. Participating in Chinese holidays or festivals, learning the Chinese language or engaging in Chinese customs are some examples. The most popular Chinese holiday widely celebrated is Chinese New Year. Chinese Indonesians share similar customs to Chinese people when it comes to Chinese New Year, such as the exchange of red envelopes called 红包 (hóngbāo), wearing red outfits and not sweeping the floors. These practices became much easier follow after the repression of Chinese culture came to an end in Indonesia, where Chinese Indonesians are now “encouraged to re-embrace their heritage while affirming their sense of belonging to Indonesia”, according to Grace Tan-Johannes' article about Chinese Indonesians learning Mandarin.

These attempts to engage in "Chinese" practices are forms of identity work, in which an individual strives to modify their identity in order to feel accepted in a particular group, in this case the Chinese people. These efforts originate in a desire to feel accepted in mainstream society, where one can fit in and not feel like an outsider.

Learning Mandarin

The Chinese language is a widely taught subject in Indonesian schools, particularly those located in larger cities, or cities with a higher percentage of Chinese Indonesian residents, such as Jakarta, Surabaya and Medan. With Chinese being one of the most used languages around the world, Chinese Indonesians view the ability to speak Mandarin as an asset for their futures and a good way to feel a tighter bond between their current identity and their ancestral roots.

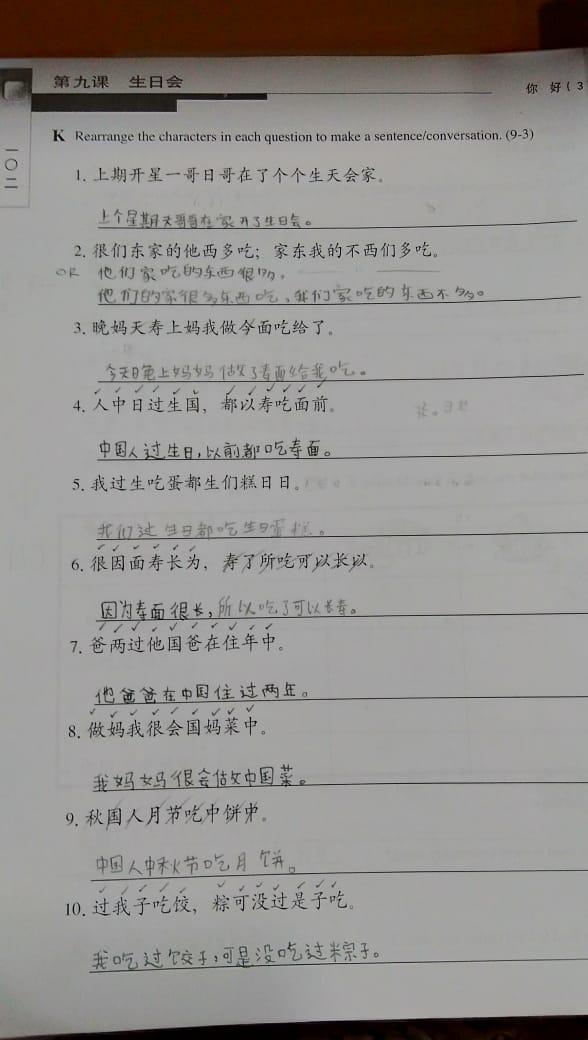

Middle school Chinese textbook for foreigners

Figure 1 is an example of a Mandarin textbook for relatively early levels of proficiency in comparison to that of a native speaker. Chinese Indonesian students are encouraged by their parents to pursue learning Mandarin from scratch in order to “understand” a little more of their roots. These parents grew up in the times when Chinese cultural practices were illegal in Indonesia: the Chinese language was not to be spoken, Chinese literature was not to be distributed and read, and Chinese holidays were not allowed to be celebrated.

As a result, this generation experiences the gap between being born in Indonesia and having Chinese ancestors. These are the Chinese Indonesians who feel as if they have strayed from their ancestral roots the most: they are the generation that considers Indonesia as their home the most.

Chinatowns

Chinatowns are places where Chinese Indonesians, particularly of the older generation, can feel and experience what Chinese urban areas used to look like. Red lanterns, Chinese food stalls and Mandarin being spoken are just some characteristics of Chinatowns. A sense of comfort and a certain feeling of belonging are what keeps these Chinatowns alive. This is where people of the same ethnicity come together to experience the familiar taste of Chinese cuisine, buy ornaments for Chinese holidays or simply experience the mutual understanding of what it feels like to not completely fit in in the “outside world".

Main entrance of the Chinatown in Cibubur, Indonesia.

Figure 2 shows the main entrance of the Chinatown in Cibubur, Indonesia. The colour red symbolises luck and joy in Chinese tradition and is found decorating Chinese-dominated areas, in addition to the red lanterns and dragons.

Loyalty to Indonesia as a citizen

Indonesia’s national motto "Bhinneka Tunggal Ika" translates to "Unity in Diversity", and people of mixed ethnicity play a significant role in this national “vow”. This form of nationalism acts as reassurance: the motto functions as an unspoken rule that every Chinese Indonesian assumes everyone in Indonesia should adhere to. This motto is a way to ensure that they are “accepted” as citizens of Indonesia despite having Chinese ancestors. Refusing to “accept” them as Indonesian citizens could be seen as disrespecting the country's values.

Despite Indonesians and Chinese Indonesians' differences in culture and religion which cause them to have mostly different customs, Chinese Indonesians also partake in some significant Indonesian traditions. Two examples are the celebration of national holidays and speaking the same mother tongue. Since they legally are Indonesian citizens, Chinese Indonesians take part in national holidays such as the Independence Day, Kartini Day (a day commemorating Kartini, one of Indonesia’s national heroes who fought for women’s right to education), and Heroes' Day. Further, Chinese Indonesians have fully adapted to speaking Bahasa Indonesia, the country's official national language, as their mother tongue. This applies to China-born Indonesian citizens too, who practice translanguaging and code-switching between speaking Chinese and Bahasa Indonesia.

So who are we?

The concept of enoughness is very helpful in examining people's desire to belong to a particular community. Individuals want to have just the right amount of identity emblems to be part of a community and, at the same time, they aim to be considered an authentic member, someone not “trying too hard”. If individuals possess either too many or too few emblems, they can be criticised for the (in)authenticity of their identity and risk being called “wannabes” or even “fakes”.

According to Blommaert and Varis (2015), "one is never a 'full' member of any cultural system, because the configurations of features are perpetually changing, and one's fluency of yesterday need not guarantee fluency tomorrow". Many Chinese traditions, for example, have fallen away and Chinese culture overall has been altered as a result. At the same time, aspects originating in different cultures may be integrated within another culture - Indonesian culture, for example, is no exception.

I, as a Chinese Indonesian myself, feel the confusion about my identity when asked whether I can speak Chinese or why I don’t look Indonesian. Is it worth the time to explain why there are such things as Chinese Indonesians? Will the people I meet understand it then?

As far as I have noticed from my own experiences, I tend to feel more “isolated” in the mainstream Indonesian community and culture when I am back home in Indonesia. It is not as bad as feeling "deviant", as Howard Becker (1963) puts it, but the presence of an unbridgeable gap between native Indonesians and Chinese Indonesians feels quite prominent to me as an individual. Being deviant in Becker's (1963) terms amounts to not conforming to social rules followed by the many and results in individuals not being accepted into a community. In the case of Chinese Indonesians, things are not so straightforward; being Chinese Indonesian feels more like being half-accepted in both communities - or nationalities in this case. This is my personal observation at any rate, which might not be generalizable to other Chinese Indonesians.

My observations and my opinion changed when I moved abroad to the Netherlands, where there is a much higher number of native Indonesians where I live. Although there is still the possibility of me being an outsider as a Chinese Indonesian, my sense of nationalism towards Indonesia grew unexpectedly here - not only through food and language, but especially through a feeling of overprotectiveness towards my home country.

It is not possible to ever identify Chinese Indonesians as either "Chinese" or "Indonesian", because we simply are not either. No matter how much we try and conform into either community, the level of enoughness we possess will not be sufficient to both. It is important to stress that the Chinese and Indonesian communities are both our communities, instead of believing that we (must) belong to only one of them, or even neither.

References

Becker, H. (1963). Outsiders: studies in the sociology of deviance.

Blommaert, J. & Varis, P. (2015). Enoughness, accent and light communities: Essays on contemporary identities. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, No. 139.

Johannes, G.T. (2018). Why more Chinese Indonesians are learning Mandarin, and nurturing their children’s sense of belonging to Chinese culture.

Suryadinata, L. (2008). Chinese Indonesians in an Era of Globalization: Some Major Characteristics. In L. Suryadinata (Ed.), Ethnic Chinese in Contemporary Indonesia (pp. 1-16). ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute.

Vertovec, S.(2007.) Super-diversity and its implications

Wallerstein, I. (2004). World-Systems Analysis: An introduction. Durham NC: Duke University Press.