Here, yet always there: How Fleabag uses Intimacy as Distraction

Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s series Fleabag (BBC/Amazon Prime, 2016-‘19) has been praised for its revitalization of direct address. ‘Breaking the fourth wall’ is a technique that has often been used (or even overused) in comedy and drama series (think of Modern Family or Arrested Development), but here it is used in an innovative way. The main character, played by Waller-Bridge, is a Londoner in her early thirties who struggles to make meaningful connections.

I examine Fleabag’s ‘confessions’ to the camera in the context of trends in self-representation of young women on social media, and argue that she uses self-disclosure as a form of self-branding, to manipulate the audience and to distract herself from painful truths. I interpret the series’ particular use of ‘breaking the fourth wall’ as distancing device that ultimately blocks, rather than facilitates, connectivity and intimacy. Fleabag uses intimacy as distraction.

Why so serious? Gendered ‘rules’ for online self-presentation

For young women especially, constant media visibility and intense social media participation have come to form an implicit norm (Banet-Weiser 2012). Not only frequency of posting, but also content is subjected to certain unspoken rules. In times of austerity, financial crisis and insecurity on the job front, neoliberal media culture asks individuals to be resilient, flexible, and positive (Kanai 2017). For young women in particular, this results in a set of contradictory expectations. They are urged to show individuality and self-confidence, to be assertive, and practice self-care. Yet, they should also be pleasant, approachable, and feminine in all aspects of daily and professional life. Moreover, they should balance all these demands with a light-hearted sense of humor.

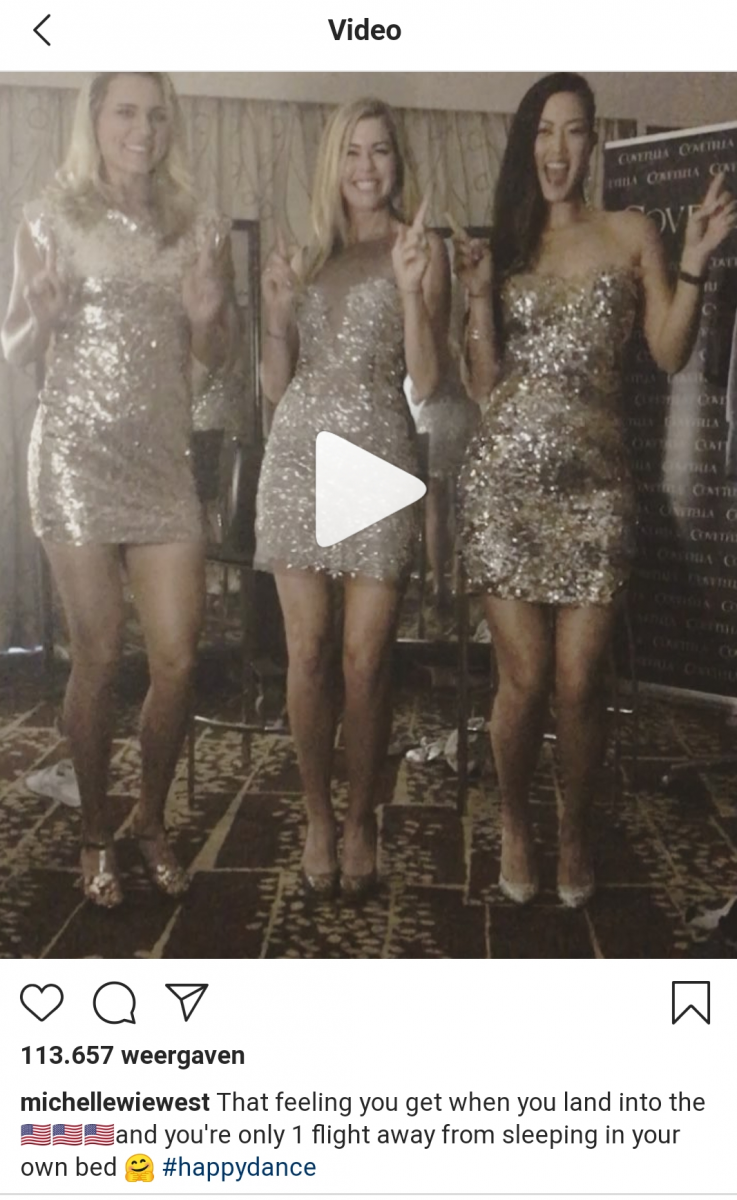

Humor is an important tool to manage the burden of contradictory expectations associated with the postfeminist moment. It serves to defuse the fact that individuals are impacted by the stress of studying, money, body standards, and relationships. The norm is to acknowledge failures and insecurities but in a lighthearted tone, not taking the self too seriously: young women often attempt to carry out values like ‘self-belief, savviness, and positive emotions’ (Kanai 2017). Such humorous self-representations produce relationships which reconfigure sociality as an audience of potential consumers of the self, marked by a gendered intimacy that becomes currency (Kanai & Gill 2018). This ‘entrepreneurial’ broadcasting of the self includes almost all domains of life, notably including those that were once considered private (McRobbie 2009).

Double Deixis: Who has a massive arsehole?

FLEABAG

(earnest, touch of pain. To camera)

You know that feeling, when a guy you like sends you a text at two o’clock on a Tuesday night asking if he can come and find you and you’ve accidentally made it out like you’ve just got in yourself so you have to get out of bed, drink half a bottle of wine, get in the shower, shave everything, dig out some Agent Provocateur business, suspender belt, the whole bit — wait by the door ‘til the buzzer goes

(buzzer goes)

And then you open the door to him like you’d almost forgotten he was coming over.

After some pretty standard bouncing you realise he is edging towards your arsehole. But you’re drunk, and he made the effort to come all the way here so, you let him. He’s thrilled. [...]

And then the next morning, you wake to find him fully dressed, sat on the side of the bed gazing at you... [...]

ARSEHOLE GUY

It was particularly special because I’ve never managed to actually... up the bum with anyone before— [...]

FLEABAG

And then he touches your hair [...] And thanks you with a genuine earnest. [...] It’s sort of moving. Then he kisses you gently. [...] And you spend the rest of the day wondering— [...] Do I have a MASSIVE arsehole?

This is how Fleabag, in the first episode, relates her extensive preparations for a supposedly casual sexual encounter, and then proceeds to give live updates during said encounter. All the while, story-time continues and Fleabag is in it, but zoning out, absent-minded. From the start (‘You know the feeling’), the viewer is intimated and implicated in and by Fleabag’s actions. Yet, who is this ‘you’ she is talking to? Should I feel interpellated, even if I don’t ‘know the feeling’ of the particular situation that is normalized through this address?

Second-person address is an inclusive manner of narration that solicits identification by drawing the reader or viewer into the fictional space through an ‘irresistible invitation’, in Irene Kacandes' words (1993). It is also a much-used rhetorical technique on social media to present personal experiences in a universalizing and engaging way. In online marketing, it is a way to hail masses while emphasizing individuality.

This strategy works particularly well because the pronoun ‘you’ is deictic. Deictic words (I, this, she, there) have no meaning out of their particular linguistic context. The word ‘you’ is empty and waiting to be filled by anyone (Rettberg 2002). In narrative, the second person pronoun can be a veiled reference to an ‘I’, that is, the protagonist who addresses herself (‘fictionalized address’). Alternatively, ‘you’ can refer to an entity in ‘our’ actual, extradiegetic world, the actual reader or viewer (‘actualized address’). However, there are cases in which it is impossible to decide whether ‘you’ is fictional or actual; this type of ‘you’ is called ‘doubly deictic’. This ‘you’ ‘produces an ontological hesitation between the virtual and the actual’ by continuously repositioning the reader (or viewer), rendering porous any border between text and context (Herman 1994). It superimposes two or more deictic roles, internal and external to the diegesis.

Whereas in Fleabag, at first we might get the impression that ‘you’ refers to the protagonist herself, and later the address seems to be directed at the actual viewers, the second person is actually doubly deictic. Fleabag reveals her awareness of the audience as a presence within the diegesis: ‘I have friends....,’ she says to her therapist, with a wink at camera, ‘Oh, they’re… they’re always there.’ It is like she admits that these asides are her way of coping with loneliness and dissatisfaction. Fleabag’s ‘you’ is both actual and virtual, with the viewer suspended between two wolds. This doubly deictic ‘you’ produces relatability, as we get sucked into her universe. We are here, but always there.

Others like us

Fleabag uses technology and performance to distract herself and her audience in a way that is similar to activities on social media. She is annotating her life continuously, commenting on what she is doing in real time (‘jogging’). She engages in a form of live streaming, the ongoing broadcasting and documenting of one’s daily life and thoughts, including the mundane and intimate. We become her co-conspirators, our complicity brought into being through the mediated nature of her disclosures, the way she uses the camera as a ‘technique of the self’ (Poletti 2012).

Viewer attention is further modulated by the close-up: Waller-Bridge performs facial mini-dramas every time she looks at the camera. As Mary-Anne Doane (2003) wrote, the close-up brings into play oppositions between surface and depth, exteriority and interiority: it gestures to a beyond. Seeing a close-up of a face, it is hard not to wonder what the person is thinking or feeling. This furthers the sense of interconnectivity evoked by the second person address.

We are interpellated as individuals who are part of a collectivity on the basis of presumed engagement in similar kinds of behavior, like prepping for last-minute booty calls whilst trying to exude nonchalance, or using a slutty crop top as a face mask

Increasingly, our subjectivity is thought of as belonging to networked collectivities. As Wendy Chun writes, the 'subject' of big data is not an 'I,' nor an undifferentiated mass, but the singular plural 'You' that groups us together with 'others like us': 'As characters in this drama, we are never singular, but singular-plural; I am YOU' (2016, 363). Similarly, in social media posts in the second person, as well as in Fleabag, we are interpellated as individuals who are part of a collectivity on the basis of presumed engagement in similar kinds of behavior, like prepping for last-minute booty calls whilst trying to present as nonchalant, or using a slutty crop top as a face mask.

The camera functions as a stand-in for each singular viewer, as when celebrities engage with their fans. As Denise Wong argues, ‘Fleabag’s use of second-person address is generalized and impersonal in the sense that who we are as specific individuals seems to matter less than the fact that we are present and observing, yet we intuit that she is speaking directly to us (the viewers)’ (2019). As in parasocial interaction, Fleabag doesn’t really know or care who ‘we’ are: she uses ‘us’ to distract herself.

Intimacy as currency

Compared to the 'rules' of online platforms, ‘post-recessional’ television series (DeCarvalho 2013) by and about young women like Fleabag have room for less positive and upbeat experiences of girlhood. Dobson and Kanai (2019) argue that such TV series—they mention among others Girls, Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, and Fleabag—reflect ‘affective dissonance’ with neoliberal modes of success and the associated positive values outlined above. Fleabag’s strategies of revelation confront the gendered norms of self-presentation of postfeminism: the space between her anonymous TV audience and her becomes an intimate public where other ‘feeling rules’ (Kanai 2017a) are in place than in either her private or public spheres. Yet, the fact that she shares unwholesome experiences does not make her more 'authentic' by default. She still uses humor to deflect insecurities and feelings of shame, guilt, and anger.

COUNSELLOR

So why do you think your father suggested you come for counselling?

FLEABAG

Um. I think because my mother died and he can’t talk about it, because my sister and I haven’t spoken in a year because she thinks I tried to sleep with her husband and because I spent most of my adult life using sex to deflect from the screaming void inside my empty heart.

(to camera)

I’m good at this.

Her blunt, comical tone defuses the pain underlying this statement, even if her audience knows that all of it is true. Her self-deprecating self-branding is marked by ‘performative shamelessness’ (Dobson 2015): a prominent pose of confidence in a digitally mediated, postfeminist context, which functions as a shield against hyper-critical peer (and self-)surveillance. Here, Fleabag opens up about her friend’s suicide to a random cabdriver:

She didn’t actually think she’d die, she just found out that her boyfriend fucked someone else and wanted to punish him by ending up in the hospital and not letting him visit her for a bit. She decided to walk into a busy cycling lane, wanting to get tangled in a bike, break a finger maybe. But as it turns out bikes go fast and flip you into the road. Three people died.

She was such a dick.

Fleabag uses performative shamelessness to shock people, to test their reactions, and thus distract them from her insecurities. Flirting with random strangers is her mode of being in the world. Fully aware of our gaze, she provokes us and flirts with the camera. Sitting on the toilet, she confesses: ‘I’m not obsessed with sex. I just can’t stop thinking about it. The performance of it. The awkwardness of it, the drama of it. The moment you realize someone wants your body . . . not so much the feeling of it’. She does not really enter into a reciprocal relationship; she likes the attention.

The connection between her and 'us' can only be described in terms of ‘weak bonds,’ in Wendy Chun’s sense: ‘the promise of an intimacy that, however banal, transcends physical location and enables self-made bonds to ease the loneliness of neoliberalism’ (2016, 117). What seems to be radical honesty is actually a strategy that serves to produce relatability.

Until the second season, in which her projected image starts to crumble, Fleabag retains control over how we see her, and how much we see. She is all performance. ‘She is so controlled,’ Waller-Bridge remarks about her own creation. ‘The clothes that she wears, she’s constantly got this red lipstick on, her hair’s perfect, she looks pristine and clean. The fleabagginess of her is her subtext’. In her carefully curated self-representations, precisely by foregrounding negative affect, she is an expert at seeming authentic while keeping people at a distance. While reserving space for affective dissonances, in the end, Fleabag’s confessions are no less staged than their happier online counterparts.

By placing Fleabag’s form of self-branding in dialogue with contemporary ‘rules’ for social media presence of young women in platform-driven attention economies, I have shown how relatability and intimacy can be strategically produced to ‘sell’ the self. In post-recessional television, perhaps more than on social media—with trends like ‘crying vlogs’ (Berryman & Kavka 2018) and ‘sad girls of Instagram’ (Holowka 2018) as notable exceptions—this does not exclude ‘affective dissonances’. Breaking the fourth wall, doubly deictic ‘you’, and close-ups all facilitate an intimacy and sense of sociality turned to currency.

References

Banet-Weiser, S. 2012. Authentic, TM: The Politics of Ambivalence in a Brand Culture. New York, NY: New York UP.

Berryman, R., and M. Kavka. 2018. Crying on YouTube: Vlogs, Self-Exposure and the Productivity of Negative Affect. Convergence 24(1): 85 – 98.

Chun, W. 2016. Big Data as Drama. ELH 83(2). 363–82.

Chun, W. 2016. Updating to remain the same: Habitual new media. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

DeCarvalho, L. 2013. Hannah and Her Entitled Sisters: Postfeminism, Postrecession, and Girls. Feminist Media Studies 13(2). 367–370.

Doane, M.A. 2003. The Close-Up: Scale and Detail in the Cinema. differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 14(3): 89-111.

Dobson, A.,S., and A. Kanai. 2019. From “can-do” girls to insecure and angry: affective dissonances in young women’s post-recessional media. Feminist Media Studies 19(6): 771 – 786.

Herman, David. 1994. Textual 'You' and double deixis in Edna O'Brien's A Pagan Place. Style 28 .3 (Fall): 378-410.

Holowka, E.M. 2018. Between Artifice and Emotion: The “Sad Girls” of Instagram. In Leadership, Popular Culture and Social Change, edited by K. Bezio and K. Yost. 183 – 195. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Kacandes, Irene. 1993. Are You In the Text?: The ’Literary Performative” in Postmodernist Fiction. Text and Performance Quarterly 13, 139–53.

Kanai, A. 2017. On Not Taking the Self Seriously: Resilience, Relatability and Humour in Young Women’s Tumblr Blogs. European Journal of Cultural Studies 22(1). 1-31.

Kanai, A. 2017a. Girlfriendship and Sameness: Affective belonging in a digital intimate public. Journal of Gender Studies 26(3): 293-306.

Kanai, A., & R. Gill. 2018. Mediating Neoliberal Capitalism: Affect, Subjectivity and Inequality. Journal of Communication 68(2): 318 – 326.

McRobbie, A. 2009. The Aftermath of Feminism: Gender, Culture and Social Change. London: Sage.

Poletti, A. 2012. Reading for Excess: Relational Autobiography, Affect and Popular Culture in Tarnation. Life Writing 9(2): 157 – 72.

Rettberg, J. W. Do you think you’re part of this? Digital Texts and the Second Person Address. 2001. Researchgate.

Waller-Bridge, F. 2019. Fleabag: The Scriptures. London, UK: Sceptre.