Netflix versus Culture: Language Policy in the Netherlands

Do you also look forward to that feeling when you come home after a long day of work, flop down on the couch and start watching a movie or series? If so, do you still do this through your television service or do you use online services such as YouTube or Netflix?

As you might have experienced, in the last couple of years the production, distribution, and consumption of ‘media content’ have changed at lightning speed (Raad voor Cultuur, 2018). Thanks to mobile devices with high-speed Internet access, media use has increased enormously. Therefore, the media landscape has seen unprecedented dynamics. This paper examines what this means exactly for the audiovisual sector, especially for its language policy. Let’s take a look at the Dutch situation.

Figure 1: What channel is The Netflix?

Marginalization or protection of Dutch content

Most of the online streaming services used in the Netherlands are owned by a handful of large US companies (e.g. Netflix). Due to their enormous economic strength, they frequently distribute (often) high-quality series, films and other content.

Additionally, due to the knowledge they gain from the streaming behavior of their large numbers of users, they are able through sophisticated marketing techniques, to react to the audiences' demands (Raad voor Cultuur, 2018). These foreign companies mainly produce international content, which means that the amount of Dutch content decreases and also that income from advertisements flows into international directions. Some are afraid that if this continues the Dutch audio-visual product may become marginalized.

Most of the online streaming devices used in the Netherlands are owned by a handful of large US companies (e.g. Netflix).

To prevent this from happening, the Raad voor Cultuur (Council for Culture), an advisory body of the Dutch government, has published a report in which they analyzed the developments in the audiovisual world from a cultural, social and economic perspective.

One recommendation they give the Dutch government is to change its language policy by introducing a (minimum) quota for the screening of Dutch films, series, documentaries, and animations for cinemas, film theaters, and on-demand platforms that are active in the Netherlands (Raad voor Cultuur, 2018). In an interview with the Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant, the director of the Council for Culture, Jeroen Bartelse, says that they are thinking of introducing a quota of 15 percent Dutch content (NU.nl, 2018). In other words, on-demand channels will then be obliged to arrange Dutch content.

The Dutch Council for Culture pleads for introducing a quota of 15 percent Dutch content for on-demand channels.

Furthermore, the Council for Culture advises to set levies, between 2 and 5 percent of the turnover, for all operators (such as Netflix) of both paid and free offline and online services. The payments gained from this will then be used to facilitate the future of the Dutch audiovisual sector and to strengthen the position of the cultural audiovisual product (Raad voor Cultuur, 2018).

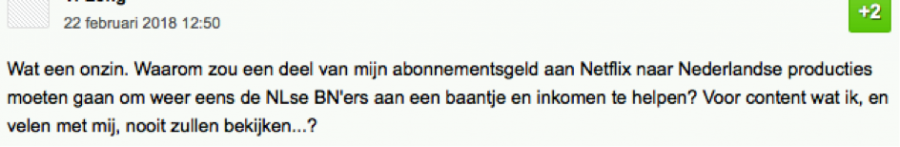

However, this advice is not binding as long as the government does not act on it. But let’s imagine that they indeed change the policies in accordance with the recommendation, and ask ourselves whether this would work. Some news organizations wrote about this possible future language policy and the reactions that were given by readers show divergent opinions. For example, in Figure 2, a reader reacted to Jansen’s (2018) column about the advice:

“What nonsense. Why should a part of my Netflix subscription fee go to Dutch productions, which once again help the Dutch celebrities to get a job and income? For content that I, and many with me, will never watch...?”

Figure 2: One of the reactions on Jansen’s (2018) column about the advice from the Dutch Council of Culture.

Top-down and bottom-up policies

Such reactions show an interplay between top-down and bottom-up practices. Thinking that a policy would work if it were purely top-down, is not realistic. It has to interact with the audience, in a bottom-up way, as well. In other words, putting together a great policy text containing a clear overview of aims and means does not guarantee that it will succeed. How people react to the policy is also important.

Nevertheless, Reed Hastings, the vice president of Netflix Originals (which is content that Netflix creates or of which they own the license), explains in a conversation with NOS (the Dutch Broadcast Foundation) that they want to get ahead of the quota and invest in all kinds of content throughout Europe. This in order to contribute to the idea of preservation of culture and reduce the need for regulation. Hastings also explains that countries that have set fixed regulations (quota), like Canada, have not produced great content (Bouwman, 2018). Therefore, they have announced that Netflix is working on a Dutch Netflix Original series.

Bartelse, the director of the Council for Culture, responded to this announcement in conversation with the NOS that it is good that Netflix does not perceive the Netherlands as just a profit region and that investments like these are crucial for high-quality productions in the audiovisual sector, but also said that one series is not enough (Bouwman, 2018).

Can Englishization be stopped?

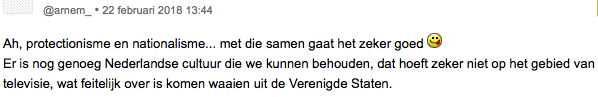

Some feel the urgency to protect the Dutch culture, which includes the Dutch language. Additionally, they seem to want to stop the process of Englishization, which is caused by economic globalization. In other words, they stress the need for negotiated multilingualism and the rights of speakers to resist global pressures and to use, maintain, and develop their local languages (Dor, 2004). However, one can wonder whether this is still possible and whether this is ideology is widely supported by the general population. For example, Figure 3 shows a reaction to Jansen’s (2018) column about the advice from the Dutch Council for Culture:

“Ah, protectionism and nationalism… these together will definitely work :p. There is still enough Dutch culture that we can preserve, there is no need to do this in the field of television, which actually came from the United States”.

Figure 3: One of the reactions on Jansen’s (2018) column about the advice from the Dutch Council of Culture.

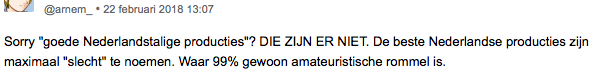

Additionally, as I read in multiple reactions to the same column, including the one in Figure 4 below, people just want good content, and not everyone trusts that this will happen if content is Dutch in origin.

“Sorry, “good Dutch spoken productions”? THEY DO NOT EXIST. You can call the best Dutch productions bad at best. Whereas 99% just is amateurish rubbish.”

Figure 4: One of the reactions on Jansen’s (2018) column about the advice from the Dutch Council of Culture.

Ideologies

What is the current situation? As mentioned, the report of the Council for Culture is not binding. Therefore, the government has to decide what they are going to do about this matter. Are they going to create a language policy that includes all the recommendations mentioned in the report or do they choose some other option? These choices will in the end always be based on certain ideologies and every governmental body needs to choose a position. Do they adopt an assimilationist ideology, which means that they ensure that the national language maintains its dominant position in society and that they do not value linguistic distinctiveness (Bourhis, Moise, Perreault & Senecal, 1997)?

In that case, they may follow the example of France, which has a quota of 20 percent French-speaking content for on-demand platforms (NOS, 2018). Or do they rather want to take a pluralist ideology, in which the state has no mandate in defining or regulating the private values of its citizens and individual liberties in personal domains (e.g. leisure spheres or linguistic and cultural activities) must be respected (Bourhis et al., 1997)?

And when the government has chosen its position, this has to correspond with the ideologies of its citizens. Because if they do not agree, then the language policy may not succeed at all. In sum, since this issue has to do with ideologies, we can safely say that the last word has not been said about it. In addition, this subject has to do with money, not just with ideology, and the combination seems a perfect cocktail for causing conflicts.

References

Bourhis, R.Y., Moise, L.C., Perreault, S. and Senecal, S. (1997). Towards an interactive acculturation model: A social psychological approach. International Journal of Psychology, 32: 369–386.

Dor, D. (2004). From Englishization to imposed multilingualism: Globalization, the Internet, and the political economy of the linguistic code. Public Culture, 16(1), 97-118.

Jansen, J. (2018). 'Netflix, Amazon en Google moeten inkomsten afstaan voor Nederlandse producties’. Received on March 22, 2018.

Bouwman, H. (2018). Nederland krijgt eigen Netflix-serie: 'we zijn ermee bezig'. Received on March 22, 2018.

NOS. (2018). Hoe Frankrijk zorgt voor Netflix-series in het Frans. Received on March 22, 2018.

NU.nl. (2018). Raad voor Cultuur wil quotum voor Nederlandse producties op Netflix. Received on March 22, 2018.

Raad voor Cultuur. (2018). Zicht op zo veel meer. Received on March 22, 2018.