No Man is an Island: Locating Breivik in Islamophobic Discourse Online

The 2011 shootings on Utoya, Norway were a shock for Europe. The shooter, Anders Breivik, stated he was acting alone and was declared a ‘lone wolf’ in the media. Prior to the shootings, Breivik created a Manifesto, for which he had done years of research. He often focuses on a concept called ‘Eurabia’, the belief that Islam will take over Europe, as popularized by author Bat Ye’or. Breivik's aim was to gain followers and establish an army in total secrecy in order to “take back” Europe.

Breivik claimed he was acting alone, but is it really possible in the digital age to act alone? The ideas Breivik describes in his Manifesto are certainly not new ideas, and he was also not the last one to think in the way he did. Seven years later, we can still see his ideas emerging in mainstream political discourse, especially with right-wing political parties.

In this article, we seek to break down the communities and movements that influenced and led to Breivik’s radicalization and follow the ripple effect of his actions to contemporary political discourse.

The blogs where Breivik found his discourse

Breivik repeatedly references three key blogs in his Manifesto: Little Green Footballs (LGF), Gates of Vienna, and the Brussels Journal. Though the content of these blogs varies, they share important themes, particularly in the realm of media deception and the concept of “jihad” in Europe. With the exception of Gates of Vienna, they very rarely mention the concept of Eurabia directly. Gates of Vienna even links an archive of Eurabia related posts on its main page. However the oldest of these posts is from 2012, i.e. the “post-Breivik” era. Therefore it is important to break down the content of these blogs not so much as a direct cause for Breivik's obsession with Eurabia, but rather as a milieu of Islamophobic paranoia that reinforced and informed his interaction with Ye'or's work. While Bat Ye’or’s book Eurabia (2005) was of course a massive influence on Breivik, in this paper we will focus on the nexus of internet communities that supported Breivik’s deep dive into islamophobic extremism.

First we will address Little Green Footballs. LGF is an American political blog run by a man named Charles Johnson. From its establishment in 2005 through around 2009, the blog was known for its right-wing politics. While a variety of factors has made tracking down specific posts referenced by Breivik in his manifesto difficult, an overview of the archives enabled us to reconstruct the kind of posts Breivik would have encountered.

A Sampling of LGF's Blog Posts

LGF's blog posts from this era frequently reference media “hoaxes”, staged or faked “fauxtos” and videos, and a general rejection of the mainstream media. Additionally, LGF's posts frequently refer to the same conceptualization of “jihad” as Breivik did. Posts with headlines like “Muslim Brotherhood Calls for Maximum Jihad” and “JihadTV Makes Deal with Sony” dominate the “Middle East” tag on LGF from the era in which Breivik would have been reading this blog and constructing his manifesto. The latter suggests a Eurabia-esque “infiltration” - Al Jazeera is trying to infiltrate your cell phones and brainwash you. A post titled “Palestinians on the Western Dole” alleges that American tax dollars are propping up what LGF considers to be a terrorist state. Posts like these tap into a central piece of the Eurabian conspiracy, the idea that western elites are actively cooperating with the Islamic takeover of Europe.

Posts like these tap into a central piece of the Eurabian conspiracy, the idea that western elites are actively cooperating with the Islamic takeover of Europe.

The Brussels Journal, a Belgian blog run by Paul Beliën, calls itself “the voice of conservatism in Europe.” Beliën’s blog entrenches the narrative that the “consensus media” is hiding the truth. Their “all time” popular posts prominently feature an entire series of posts about the controversy over a Danish newspaper’s depiction of Mohammed, as well as accusations that immigrants are “waging war” in Sweden.

Further, the Gates of Vienna blog features an entire section on the history of the counterjihad movement, as well as the posts of the blogger “Fjordman”, which Breivik wholesale copy-pasted into his Manifesto.

Klein (2017), in his work on American hate groups online, highlights how,

“Not unlike the alarmist language that is often voiced during legitimate times of national security crises ... the discourse found in today’s racist and radical websites carries similar tones of alarm, fear, outrage, resistance, and action.” (p. 118).

We see this across all three blogs - a fear and resistance to mainstream media, and alarm about the “Islamization” of Europe. Further, all three blogs feature incredibly active comments sections that Breivik participated in. Thus these blogs provide not just Breivik’s “evidence” for his arguments, but also a large community that continually reinforces these views. In short we can say that Breivik, while alone in his actions, is hardly alone in his ideology. His Manifesto references and outright copies a community that echoes his rage and supports his obsession with Eurabia. How can we call him a lone wolf when he cites his sources?

Breivik as Flashpoint

George Herbert Mead theorized that an individual can only develop a total individual self if she/he seizes the attitudes of an organized social group of which she/he is part and cooperates with social engagements in which that group is involved. Further, individuals belong to a community whose practices control the behavior of individual members. Being involved in social interactions or in a community is an essential factor of the thinking of a single individual. An individual develops his own unique personality because she/he belongs to a community from which he incorporates the foundation of that society into his own behavior (Mead, 1934). This can also be seen in the case of Anders Breivik. So, was Breivik really that alone?

Individuals develop their own personality because they belong to a community

The attacks committed by Breivik seemed to appear out of nowhere and highlighted the threat of lone wolf terrorism in Western nations. The term lone wolf terrorist is difficult to define, as there is much discussion and debate over it. In the broadest sense the term can be defined as: “terrorists that operate individually, do not belong to an organized group, and are difficult for authorities to detect” (Berntzen & Sandberg, 2014). Although lone wolf terrorism seems to be a relatively recent phenomenon, cases of single individuals committing terrorist attacks can be found from the 19th century forward. Different from prior attacks, Breivik’s act, when contextualized by his manifesto, is characterized by the power of the internet. The internet served as a powerful tool for Breivik to both gather information and distribute his extensively researched manifesto (Appleton, 2014).

Although Breivik committed his terrorist attacks as a single individual, the reason he committed the attacks were most likely inspired by a broader anti-Islamic social movement. In his manifesto, Breivik describes the rhetoric of the anti-Islamic movement across Europe and the United States which has appeared to expand exponentially, in large part thanks to the speed and scope of information sharing online (Berntzen & Sandberg, 2014).

The internet is a medium that helps people to spread ideas at a rapid pace. Since the 9/11 attacks, anti-Islam movements have developed quickly. Much of the ideology of this movement was spread through blogs and heavily biased “news” sites, such as Gates of Vienna. In the post-Breivik era, both radical Muslim youth and their far-right anti-jihad contemporaries use the internet to widely share their views (Turner-Graham, 2014). For organizations like anti-jihad movements, the internet is a gateway through which to distribute their views and connect their organization to the mainstream media.

Klein notes that hate groups like these anti-jihad movements rarely use recognizable hate symbols anymore. Instead they ingratiate themselves into the discussion of daily news items such as national politics and popular culture. Especially on community forums where these views are already accepted, the community aspect serves to reinforce these views. Today, these radical opinions have found their way into the mainstream web through search engines, news websites and wikis, political blogs and social networks and video sharing websites (Klein, 2017).

Politics Post-Breivik

There is a substantial growth of political forces in Europe that focus on right-wing nationalism and the creation of a homogeneous community, e.g. Forum voor Democratie in the Netherlands, Alternative für Deutschland in Germany, Rassemblement National in France, and Schild en Vrienden in Belgium (Van Houtum & Bueno Lacy, 2017). What most of these political parties and right-wing organizations have in common is that the “enemy” is always the national elite and Muslims working together (Berntzen & Sandberg, 2014). This goes hand in hand with Breivik’s Eurabia thought, which may indicate that Breivik’s Eurabia ideology is reflected in contemporary politics. Blommaert (2018) even states that Flemish organization Schild en Vrienden actively uses the online extreme right-wing world that Breivik created for their own ideas and ideologies.

However, it is important to acknowledge that these right-wing political parties intentionally make themselves visible in mainstream media. This is in contrast to the ‘lone wolf’ Breivik, who kept himself out of the media view until the attack itself. A possible explanation for this shift could be that due to new technologies of mass mobility, knowledge is quickly spread among a large audience (Appadurai, 1996). Meaning that the internet and its infrastructure established a space where explicit racism against Muslims could become increasingly visible in public discourse (Ekman, 2015).

Moreover, Maly (2018) explains that such groups use the digital infrastructure to recruit, train and mobilize. Consider the strategy of Schild en Vrienden for instance: they explicitly communicate in English, which refers to their global character (Maly, 2018). Besides, they effectively use Facebook’s algorithms, which are designed to create communities of people who share the same interest or opinions (Blommaert, 2017). Schild and Vrienden advocates for their followers to immediately engage with their posts by the means of liking, sharing, commenting and tagging so that Facebook ‘highlights’ this post and makes sure that other people see it. This means that people within those communities experience an ‘echo chamber’ effect, in which they are continually exposed to content that reinforces their existing discourses (Blommaert, 2017). Through effective mass communication and provocative politics, they have drawn the attention of the mainstream media.

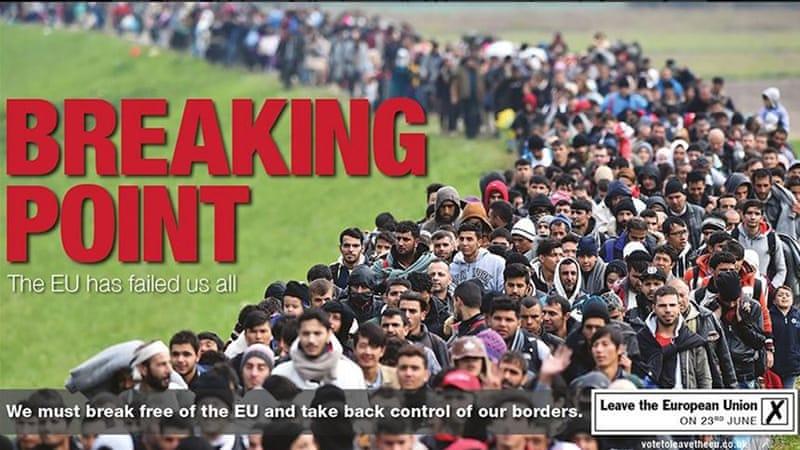

Another important case of post-Breivik politics is the Brexit, since it is the visible result of a campaign that has striking similarities to Breivik’s Eurabia ideology. The Brexit campaign focused specifically on the United Kingdom taking back the control of their own borders, especially aimed at the Muslim immigration (Van Houtum & Bueno Lacy, 2017). The notorious poster of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) connects seamlessly with the Islamophobia used in the public discourse. Additionally, this poster contextualizes associations of the refugee crisis and immigration and presents the world a reasonable truth (ergoic) to believe: “the United Kingdom needs to take back their borders” (Blommaert, 2018).

These are only two examples of the post-Breivik era in which elements of “Eurabia” have wormed their way into contemporary politics and mainstream media. That is to say that post-Breivik right-wing politics operate in a way that does not affiliate with Breivik’s norms of acting in the shadow, but nonetheless utilize and communicate his ideas.

UKIP campaign poster

No Man is an Online Island

Breivik was sentenced in his trial as an individual, a “lone wolf”. However, as seen in the Manifesto, Breivik borrows his concepts from various sources and communities - he is hardly someone acting completely alone. What we can see from these communities is that there have been groups sharing right-wing and nationalistic ideas long before Breivik, and have continued to do so after. The difference now is that these communities are gradually pushing themselves further into the public sphere online, such as ‘Schild en Vrienden’. The Brexit gives us a good example of how online shared ideas can move to an offline sphere.

Breivik’s Manifesto exhorts his followers to operate in secrecy - it is possible a great deal of them are. However, groups like Schild en Vrienden seem to be having much more success communicating their ideals by placing themselves in the spotlight. When we entertain the myth of the ‘lone wolf’, we ignore the fact that Breivik was a massive road flare pointing us to these dangerous communities. No man is an island, particularly one radicalized enough to shoot up a literal island. Breivik alone is ultimately a tragic footnote in Europe’s history - the discursive community around him will not be.

References

Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis, United States: University of Minnesota Press.

Appleton, C. (2014, March 20). Lone wolf terrorism in Norway. The International Journal of Human Rights, 18(2), 127-142. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

Blommaert, J. (2018b). Durkheim and the Internet: On Sociolinguistics and the Sociological Imagination. London, England: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Blommaert, J. (2018a, September 11). Niet Hitler maar Breivik is het model voor Schild en Vrienden. Retrieved September 15, 2018.

Ekman, M. (2015). Online Islamophobia and the politics of fear: manufacturing the green scare. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 38(11), 1986–2002. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2015.1021264

Klein, A. (2017). Fanaticism, Racism, and Rage Online: Corrupting the Digital Sphere. New York City, NY, USA. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

Lars Erik Berntzen & Sveinung Sandberg (2014) The Collective Nature of Lone Wolf Terrorism: Anders Behring Breivik and the Anti-Islamic Social Movement, Terrorism and Political Violence, 26:5, 759-779, DOI: 10.1080/09546553.2013.767245

Maly, I. (2018, 10 September). Waarom Schild en Vrienden geen marginaal fenomeen is. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

Mead, G. H. (1934). The Self. In Mind, Self and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Retrieved September 18, 2018.

Turner-Graham, E. (2014). "Breivik is my Hero": The Dystopian World of Extreme Right Youth on the Internet. Australian Journal of Politics and History, 60(3), 416-430. Retrieved September 16, 2018, from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/ajph.12070

Van Houtum, H. J., & Bueno Lacy, R. (2017). The political extreme as the new normal: the cases of Brexit, the French state of emergency and Dutch Islamophobia. Fennia. International Journal of Geography, 195(1), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.11143/fennia.64568

Ye'or, B. (2005). Eurabia. Vancouver, Canada: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.