Privacy vs. Big Data: Who are we in the eyes of tech giants?

Privacy, or rather lack of privacy, and online media platforms go hand in hand with endless scandals and worrying Terms of Service updates. In the contemporary setting, Big Data became the new gold. Users ‘pay’ by providing access to their data for the use of online content of which platforms are mediators. However, it is pretty easy to fall victim to the rhetoric of endless data sharing. What do platforms know about us? Are the key Big Tech players really that bad?

The current paper is going to answer the question of who we are in the eyes of platforms. Online mediums can treat us merely as profiles of data collections, however, this information can be built on assumptions that are not accurate or complete. Different mediums can have access to various bits of users’ data being more or less precise in their assessment.

Starting with the literature review, this paper will zoom into two case studies to explore the nature of platforms’ data collection. By looking at Google ad settings profiling, and comparing it to Apple’s user data files, we are going to investigate how tech giants perceive and categorize their users. This paper is also going to provide a set of alternative solutions for users to manage their privacy, embracing their role in the system as agents rather than mere collectibles of data points.

Privacy, platform ecosystems and Big Data

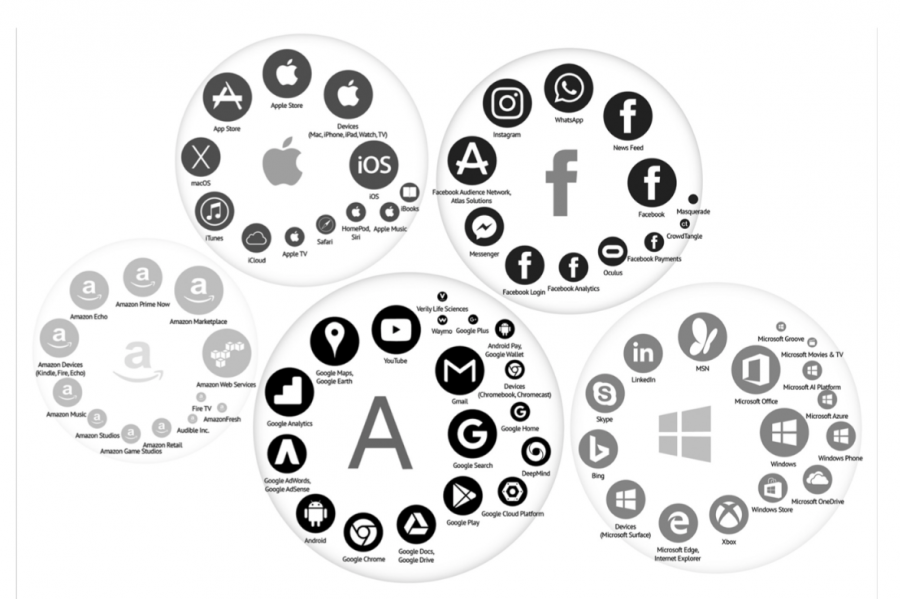

Privacy on most of our online platforms in Western countries is regulated by five high-tech companies which are the monopolists of users’ everyday digital experiences. Alphabet-Google, Facebook, Apple, Amazon, and Microsoft create an ecosystem full of paradoxes (van Dijck, Poell, & de Waal, 2018): apparently egalitarian, they are in fact hierarchical; even though they are almost entirely corporate, they still claim to serve public value; although neutral-looking, adhering to certain ideologies; entirely global but with local influence (van Dijck et al, 2018).

The Big Five are the most influential players in the platform ecosystem (Figure 1). This is due to their infrastructural nature, which has evolved over time. The platforms form a cluster of many apps and sites owned and managed by the Big Five (van Dijck et al, 2018). This monopoly gives platforms the ability to impose rules regarding Terms of Service on millions of their users worldwide.

Figure 1: Platforms' ecosystems scheme taken from van Dijck, et al. (2018).

Google, one of the platforms talked about in this paper, is part of the Alphabet corporate umbrella offering its numerous services. The ecosystem consists of: “a search engine (Google Search), a mobile operating system (Android), a web browser (Chrome), a social network service (Google+), an app store (Google Play), pay services (Google Wallet, Android Pay), an advertising service program (AdSense), a video-sharing site (YouTube), and a geospatial information system (Google Maps, Google Earth)” (van Dijck et al, 2018:13), as well as Google Cloud Platform, Google Compute, and others. The platform cluster means a fertile ground for Big Data collection.

Our point of departure here is Big Data and its database logic. boyd and Crawford (2012:663) describe Big Data as massive quantities of information produced by and about people, things, and their interaction, and thus a cultural, technological, and scholarly phenomenon that rests on the interplay of technology, analysis, and mythology that provokes an extensive utopian or dystopian rhetoric. These Big Data sets can be enlarged with the information that Google or Apple can gather from our advertisement settings.

Big Data gave way to what Manovich called database logic. This logic entails favouring collections of individual items with the same significance over telling stories (2001:218). This means that the algorithms at work do not look for a story but merely correlations between words and put these on the same level. This way, the algorithm cannot make sense of how these words are related, only that they are related. Because these words are on the same level, the Big Data set is often seen as something objective, but we all need to remember that there was someone who made the outlines for the Big Data set – so there is always some subjectivity in the categorization of words.

With the extensive example of the algorithmic profiling of a so-called ‘terrorist’, we see that there were a few benchmarks or norms to ‘become’ one.

Big Data with its database logic makes it possible that people can become a measurable-type and can be misjudged by the algorithms. Cheney-Lippold describes a measurable-type as a data template, a nexus of different datafied elements that construct a new, transcoded interpretation of the world (2017:47). This notion is largely based on Goffman’s ideal type where a stylistic, constructed coherence is manufactured between setting, appearance, and manner (Cheney-Lippold, 2017:51). The ideal type, and thus in a way the measurable-type, produces a norm, something that happens more often. With the extensive example of the algorithmic profiling of a so-called ‘terrorist’, we see that there were a few benchmarks or norms to ‘become’ one. For our paper, we could see what kind of ‘measurable type’ we were; namely the age category, the country we live in, or what our interests are. However, just as for the ‘terrorist’, we do not know how we met the benchmarks for these categories. The users cannot do anything to change it, except to shut down the ad settings.

There is also a little less radical algorithmic profiling than that described by Gillespie : now “algorithms play an increasingly important role selecting what information is considered most relevant to us – a crucial feature of our participation in public life” (Gillespie, 2014:167). Google Ads works exactly for that purpose. These ad settings thus have a say in both the algorithmic profiling that Cheney-Lippold describes, by putting us in categories, but also have a say in the algorithmic profiling touched upon by Gillespie , in the sense that these categories in practice show us ads that confirm our categorization.

Figure 2: Panopticon visualization.

Algorithmic profiling can also be related to the concept of the panopticon, which was formulated by the social theorist Jeremy Bentham, in the 18th century. In short, the panopticon is the perfect prison system where one guard watches from a tower, over individual cells (Figure 2). The guard can see everyone, but the prisoners cannot see him, thus in fear of being watched, they self-regulate their behaviour. Foucault used the panopticon to refer to the institutionalisation and systems of control such as prisons, schools, and asylums (Foucault, 2008).

Through a panopticon, the ultimate monitoring (thus data control) can be achieved: individual cells in a panopticon resemble the individualised data gathered by algorithms on the Internet. Foucault argued that panopticons can control their victims “because, without any physical instrument other than architecture and geometry, it acts directly on individuals; it gives ‘power of mind over mind’” (Foucault, 2008). In a similar fashion, algorithms can do that both by influencing our web surfing experience, or by feeling ‘watched’ or ‘listened to’, when getting certain recommendations that match our needs. At the same time, the algorithms are not known to the users, similarly to the prison guard in the panopticon.

With this theory in the back of our minds, we will demonstrate two case studies. First, we will draw a comparison between general knowledge and specific knowledge that Google ‘knows’ about us. Then, we will look at the differences or similarities of what Google or Apple ‘knows’ about their users.

Case Study on Google and Apple’s ad settings

For this research, the four authors have collected data from their own Google and Apple advertising settings. By consulting the information the tech giants make available to their users, we have tried to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the algorithmic identities formed by Apple and Google.

Interestingly, all authors had a private Google account to use for the data sample. However, only one author also had an Apple account to retrieve data from. This implies there might be differences in the priorities in their devices and services that attract users with different needs. We will later return to the different positions Apple and Google hold within the ecosystem of the platform society, and how this directly impacts the ways in which they collect and utilize data about their users.

General or specific ‘knowledge’

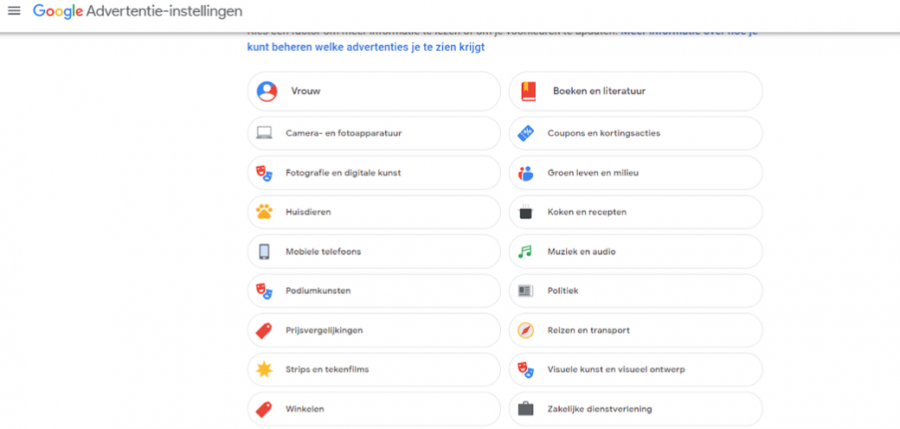

Our first case study focuses solely on Google’s ad settings and contrasts general and specific knowledge. We were able to draw this comparison as one of the authors had not given Google permission to collect data for advertising purposes. This case study will detail how the platform quickly generated data once the ad settings were changed, and how they are different from long-term users of Google with their advertising settings on.

The moment Sabine, one of the authors, turned on her ad settings, Google quickly generated eighteen categories that she fit into (see Figure 3). One of them was filled out by the author: her gender. All of the other interests were based upon data she did not want to be collected. Gender seems to have been a key category upon which several other categories were added to the list. Interests like shopping, cooking or the arts are derived from stereotypically female gender roles and character traits (Bem, 1974; Eagly, 2014; Lippa, 2001), and may have been added to the author’s ad settings based on gender stereotypes.

Figure 3: A screenshot of Sabine’s ad settings, retrieved from https://adssettings.google.com/

Other categories seem to mostly rely on other factors, like personal interests or the field of study in which Sabine is active. However, as will become evident from the comparison with the data retrieved from Madelief’s settings, the categories are rather generic. As Figure 3 shows, it states interests in music and audio, though it is unspecified which genres.

Another author, Madelief, had her ad settings turned on for a long time, which granted not only much more information but also a much more detailed algorithmic profile. Sabine’s eighteen categories almost seem meager compared to the more than a hundred categories on Madelief’s ad settings page, ranging from age estimates to relationship- and marital status, location, and interests specific to very niche genres of music and entertainment. Even though some things were fairly accurate, like age or interests, some things were completely incorrect.

Specificity and accuracy are thus the defining contrasting factors. Sabine’s profile was much less specific, and therefore all categories were in some way relevant to the author. The accuracy was rather high due to the vagueness of the data assumptions. An interest in music and audio, due to its broadness, is more likely to apply to Sabine as it may include any personal interest or niche genre. However, translated into the actual ads she would receive, it would not be really specifically targeted, and the author may have no interest in them due to this lack of specificity.

This is of course different when the categories in the ad settings are much more specific. A list of genres, ranging from world music to rock music is much more specific, however, Google is more likely to be inaccurate. As a result, the ads Madelief receives may be more tailored to her personal interest or miss that precision completely. Thus, the categories that make up one’s algorithmic identity need some sort of accuracy to even appear relevant to the user, although, ads that are too precise may miss their mark.

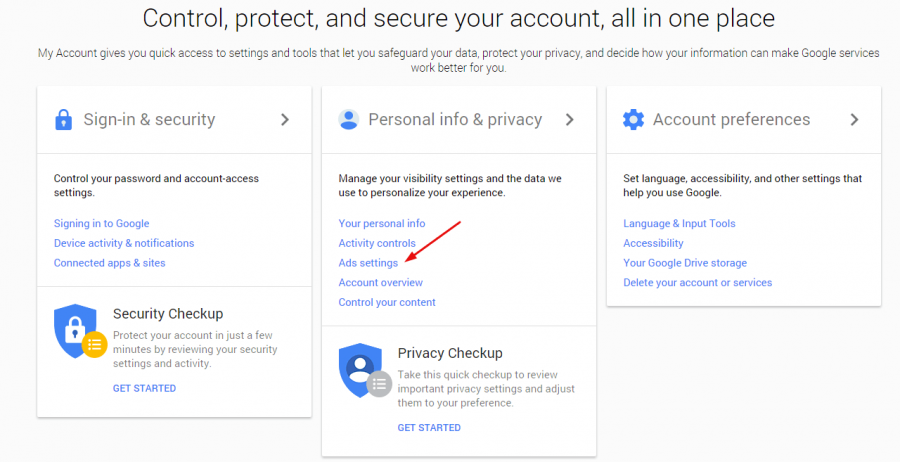

Figure 4: Google account interface leading to ads settings.

We have to take the algorithmic identities as composed by Google with a grain of salt. Though their categories are based on actual user behavior, the company’s interpretation is not an identical copy of the persons we are offline. There will always be a discrepancy between the person and their digital transcoding due to the aspects that are indicated as important for the measurable-type in the algorithm.

The authors’ choices to allow Google to gather information for advertising purposes are highly personal, however, such choices may have great implications. As van Dijck (2014) describes, data are now turned into a currency for security and online services. This data-tracking allows us to breeze through our days, not having to think twice as we open Google Maps to navigate from one place to another, or having Apple pick out songs based on what we listened to before during our daily commute. Gillespie (2014) also underscores this: algorithmic selection is an integral part of our public lives.

Interests of Google and Apple

One of the other authors, Carmen, who has used Google ads settings for more than a decade, has experienced an algorithmic identity quite close to the offline version of her. However, from extremely specific details such as the genre of the music and the genre of video games that she likes, it also recommended the stereotypical gender categories such as ‘cooking’ and ‘flowers’, thus combining both general and specific traits. In addition, it seems that the longer we use Google ad settings, the less accurate the data can become because people change as they age. Something we clicked on years ago can still be traced back to the profiling that Google has made. There are also filler assumptions that are totally unrelated and that can come from merely clicking on the wrong website. Carmen’s profile contained wrong information based on things she misclicked long ago.

Whilst Google is more involved in selling the data that they collect to third parties, Apple has a different strategy and business model. Privacy and security are two features that Apple claims to protect. There is, however, a clear difference between Google and Apple, as Apple only uses the data collected within their own ecosystem of advertising, and does not sell it to third parties. This, for many, can be a huge advantage in comparison to owning an Android phone or using Google services.

For Nataliia, one of our authors who uses Apple, the profile that Apple made about her did not disclose as much information as Google did. The data that Apple collected was about apps regarding audiobooks, books, movies, music, and tv with no detailed explanation of preferences and no in-depth ‘data profiling’. The assumptions that Apple made were mostly accurate, with a few exceptions regarding the TV interests, but they were way fewer assumptions than Google provided. However, Apple indexed gender, birth date, and address. With this in mind, Apple also stores sensitive data in their system, without the user’s knowledge. This can happen by having the ‘Frequent Locations’ setting turned on, which tracks your home and office locations, an option that is tucked away in the privacy settings and that some people might not be aware of. In the case of Google, the user usually fills in this sensitive information themselves, as this is not present in the ad profiling of Google.

Figure 5: Apple privacy statement.

As danah boyd (2010) argues, “privacy is not dead, but privacy is about having control over the information flows”. In both cases, having control over data owned by Google or Apple is impossible, because once they start collecting data, this data does not belong to the user anymore. Google is one of the most notorious data collectors in the platform ecosystem (van Dijck, 2014). By expanding to many services, ranging from the Google web search engine to video sharing and geolocation, Google can collect data of all sorts, which then is used to create highly detailed advertising profiles that are sold to third parties for profit. A recent scandal involving Google, shows that Google has been tracking its users even when using the private mode on their browsers. Consequently, Google faces now a 5 billion dollar lawsuit in the U.S. (Stempel, 2020).

It is up to the user to trust these companies, and due to Apple’s successful marketing that targets user privacy, data might be more secure if collected by Apple. However, one of the most recent data scandals that Apple was involved in, the so-called ‘Fappening’ happened in 2014, when 4chan hackers data breached Apple iCloud service and leaked nudes of celebrities. In response to this event, Apple has defended their services claiming that: “Our customers’ privacy and security are of utmost importance to us. After more than 40 hours of investigation, we have discovered that certain celebrity accounts were compromised by a very targeted attack on user names, passwords and security questions, a practice that has become all too common on the Internet.” (statement on apple.com official website). This proves that data can not be protected once it is out there.

Another debunk on Apple and their so-called data protection is the fact that they benefit from doing business with data privacy offenders such as Google. As much as the CEO of Apple claims that “We at Apple believe that privacy is a fundamental human right”, Apple has, by default, directed Safari web browser to the Google search engine, which allows Google to gather data from Apple users (Bogost, 2019). Perhaps, storing our private photos is not such a great idea because data breaches can always happen and not even Apple, one of the companies that value privacy, can guarantee with 100% certainty that their services are impenetrable.

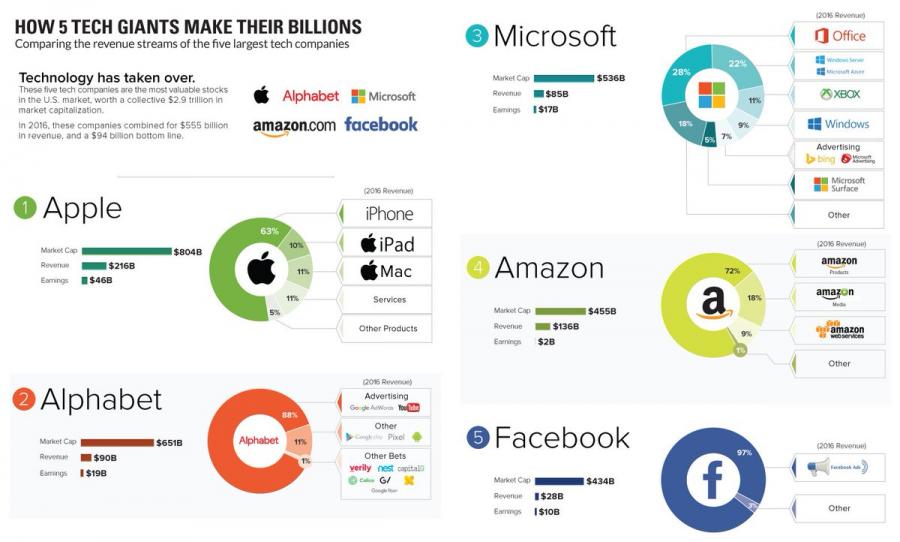

Figure 6: The infographic shows that big tech companies mostly profit from Market Capitalization.

In sum, data tracking is a double-edged sword: on one hand, it makes our everyday life easier, on the other hand, such datafication of our everyday doings allows tech companies to track our moves, translating into targeted advertising that they directly profit from, or even privacy issues. Thus, it is important that users of services like the ones provided by Apple and Google are aware of the two sides of the coin. Their services bring convenience and comfort, but is that a price you are willing to pay with your personal data? This brings us to the question of agency and what choices are left for the user, which we will address in the next section.

Agency

The commonly accepted rhetoric in relation to platform usage is the one where Big Tech companies are portrayed as purely evil instances that steal data from their users. Such a worldview makes it easy for us, platforms’ customers, to fall into the victimhood mindset thinking that we do not have any agency in the battle for our privacy. However, this is not exactly true and users still have ways to secure their private data.

Data gives tech companies billions of dollars of profit yearly (Johnson, 2021). We, users, therefore, function as free digital labourers making corporations prosper. However, it would be limiting to say that it is our only function. After all, users do have agency over the choices they make online and what tech providers they use. We are still tech giants’ clients and they depend on every one of us in their business schemes.

Platforms are dependent on individuals making use of their services.

Firstly, one needs to bear in mind that platforms are dependent on individuals who make use of their services. It is up to every one of us to sustain the the Big Five current profit system. However, although many of the users’ life domains are centered around the platform usage, namely working efficiency or social life practices, there is still a possibility to for change. Individuals and companies can choose in favor of decentralized platforms with clear privacy policies that have transparent communication about data usage. Though the ecosystems nudge users to continually rely on their services, no one is obliged to keep using Google or other tech giants but everyone does it by default, convenience, or out of fear of missing out.

Secondly, while looking at the case studies it often seemed as if the platforms tried to fix every detail about our lives. Things we searched for years ago, minor details of our lives, hobbies we were once interested in. The details they did not know about their users were filled in with the help of algorithms. However, there are a few simple steps any of us can take to (at least) prevent data collection by tech giants. For instance, one can use VPN to privatize their searches, surf online anonymously, track and frequently delete third-party cookies, use privacy extensions, manually turn off any kinds of data selections you do not want platforms to have about you.

The big tech corporations need us. Major platforms keep on working on their updates to keep us, customers, satisfied to maintain the existent data-centered profit system. Appealing services and addicting interface functions are developed to make the platforms attractive for the users who choose to then voluntarily use them every day.

Discussion: do we really have 'nothing to hide'?

The current research gives us a comprehensive overview of what data Google and Apple gather from our online activity. Still, we have to take into consideration that Google is a Big Data company, living from the ad revenue, and that Apple is a tech company, living from the sales of digital devices. These are two vastly different motives to collect data, that is why in our analysis we see that Apple takes a more passive stance than Google in order to gather information.

There is no real escape from the nudge of sharing information. Some people have been hesitant to give in and found other alternatives to these Big Data companies, like DuckDuckGo or Ecosia as alternatives to the ‘standard’ Google Search Bar. Another example from another letter of the Alphabet is Telegram as an alternative to Facebook’s WhatsApp. This app has taken flight in a few countries (Statista, 2021), but if not enough people are using the alternative as well, there is no use for it; people cannot opt-out with regard to WhatsApp, it is omnipresent.

If you gave in to sharing information, there are two issues to keep in mind; the ‘Nothing To Hide’-principle and the fact that Google or Apple gathers information about you without an assigned purpose first. The ‘Nothing To Hide’-principle comes down to the basic counter-argument for dataveillance; ‘nothing to hide, nothing to fear’ ( see boyd, 2013 for more details). This can become problematic because you do not know what is being gathered from you as dataveillance encompasses more than most people think. The phrase ‘convenience will kill us all’ is only valid in this regard as people are not aware anymore that this collectionhappens.

We could extend the reasoning that this unsupervised modeling – where there are no preset models saying ‘this is a woman’, ‘this is a terrorist’, or ‘this person likes rock music’ – fits in the panopticon that was first described by Foucault in the 1970s and explained previously. This panopticon is based on the modern prison where all prisoners could be watched by the guard; this possibility of being watched is enough for them to behave and is enough for us to behave online in a certain way (Vanden Abeele, 2020, personal communication; for more information, see McMullan, 2015).

Who are we in the eyes of tech giants?

In the eyes of tech giants, we are first of all customers whom they try to please by their new policies and implementations. We are also a source of income and free digital labour allowing for data collection. In the meantime, each of us is a collection of unique data points expanding daily. However, we are also agents who make daily choices to keep on giving up our data to Google, Apple, and other tech giants.

The relationships between online and offline identities of users have proven not to hold a 100% accuracy, which is a rather positive sign in terms of data privacy. However, a worrying fact was the information that had stayed online in the system from years before. This means that everything we ever put on the internet stays on the internet, even if we do it via Google search. Having this in mind, it is logical to assume that the algorithms will only improve in our data profile collections.

What we have seen in this analysis is whichad settings appear to be most important for Google and Apple. We saw the differences between a short- and long-term use of these settings and the differences between tech company Apple and Big Data company Google. Our literature review showed the relevance of this field and we extended that knowledge with our self-studies on ad settings. With vital topics in the back of our minds, we analyzed what Google and Apple wanted in terms of information, without finding out their purpose. Information is gathered through the usage of the internet and that raises questions of agency, the ‘Nothing To Hide’-principle and the panoptic atmosphere the internet has adopted over the years. When we are living our lives more and more online, should we be bothered with dataveillance? If we have nothing to hide, do we really have nothing to fear?

References

Bem, S. L. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. The Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42(2), 155-162.

Bogost, I. (2019). Apple's empty grandstanding about privacy.

boyd, danah. 2010. Privacy, Publicity, and Visibility. Microsoft Tech Fest.Redmond, March 4.

boyd, d. and Crawford, K. (2012). Critical questions for big data. In: Information, Communication & Society 15(5), 662-679. DOI: 10.1080/1369118X.2012.678878.

boyd, d. (2013). Where “nothing to hide” fails as logic. [Online Article].

Cheney-Lippold, J. (2017). We Are Data. Algorithms and the making of our digital selves. New York: New York University Press. ISBN: 978-1-4798-5759-3.

van Dijck, J. (2014). Datafication, dataism and dataveillance: Big data between scientific paradigm and ideology. Surveillance & Society, 12(2), 197-208.

Eagly, A. (2014). The science and politics of comparing women and men: a reconsideration. In M. Ryan, & N. Branscombe (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of gender and psychology (pp. 11-28).

Foucault, M. (2008). Panopticism. From "Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison". Race/Ethnicity: Multidisciplinary Global Contexts, 2(1), 1-12.

Gillespie, T. (2014). The relevance of algorithms. In: Gillespie, T., Boczkowski, P. J. & Foot, K. A. (eds.) Media technologies: Essays on communication, materiality and society. MIT Scholarship Online, 167-193.

Johnson, J. (2021). Google: global annual revenue 2002-2020. Statista.

Lippa, R. A. (2001) On deconstructing and reconstructing masculinity-femininity. Journal of Research in Personality 35, p. 168-207. doi:10.1006/jrpe.2000.2307

Manovich, L. (2001). The Language of New Media. Cambridge, Massachusetts/London, England: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-13374-1.

McMullan, T. (2015). What does the panopticon mean in the age of digital surveillance? [Online Article].

Statista. (2021). Most popular global mobile messenger apps as of January 2021, based on number of monthly active users. [Interactive graph].

Stempel, J. (2020). Google faces $5 billion lawsuit in U.S. for Tracking 'private' internet use.

Apple’s statement can be accessed at: https://www.apple.com/sa/newsroom/2014/09/02Apple-Media-Advisory/