Playboy's Postfeminism Problem

Hugh Hefner has passed Playboy's reigns to his son, 25-year old Cooper Hefner, but a fresh set of eyes in the creative lead at Playboy does not, unfortunately, mean any sort of victory for women.

Playboy: feminism or postfeminism?

The gentleman’s lifestyle magazine and brand has had a tumultuous 18 months in which they announced the removal of nude photographs, a choice which the young Hefner was opposed to from the start yet seemed to be a successful decision in the first months, and later reversed the change under Cooper Hefner’s newly instated creative leadership. Cooper Hefner claims the reinstatement of nudity has helped the brand and magazine to “reclaim” their “identity,” and, bizarrely and problematically, he has done so under the guise of feminism.

While both of the recent re-brandings were prompted by an economic need to sell more magazines, there are certainly broader sociocultural influences at play, which Cooper Hefner attempts to address in an essay about Playboy's philosophy. The latest issue of Playboy, dated March/April 2017, features the slogan "Naked is Normal" in its effort to reclaim lost subscriptions and advertising revenue. The young Hefner also recruited his fiancée, actress Scarlett Byrne, to both undress for a photo spread and write her own accompanying essay that promotes her choice to pose nude as distinctly feminist in nature.

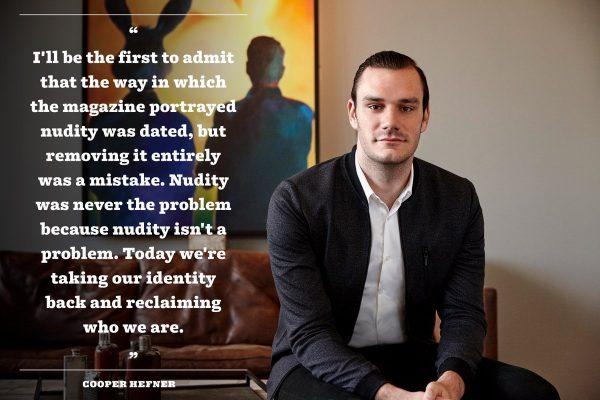

Cooper Hefner's statement on Instagram

With this, Playboy is attempting to capitalize on the present resurgence of feminism and its visibility in contemporary media, as Rosalind Gill discussed in a 2016 article. In recent years, proclaiming oneself a feminist has become increasingly fashionable, even “stylish, successful, and youthfully hip” (Gill, 2016, p. 610), especially with celebrities like Emma Watson, Beyoncé, and Benedict Cumberbatch proudly adorning the label; the feminist conversation is now profitable and significantly mediated.

Playboy is attempting to capitalize on the present resurgence of feminism and its visibility in contemporary media

However, much of this reappearance of feminism is in fact postfeminist in nature, and the reborn Playboy, Byrne’s essay especially, is no exception. To claim otherwise, that sexualized depictions of woman are not only ‘normal’ but indeed aligned with feminism and the political battle for equal rights, fosters dangerous and problematic messages to men and women alike. To simultaneously imply that Playboy’s (“reclaimed”) longstanding identity is fundamentally feminist verges on comical.

Feminism as the end of oppression

Byrne’s “Feminist Mystique” essay avoids the discussion of how her recent actions in the Playboy realm promote any sort of political agenda which works towards the equal treatment of women in society. Byrne was not wrong in saying that feminism encompasses everything from equal wages to the free the nipple campaign, but she has done little to affect the feminism conversation by freeing her nipples for a publication which has long been associated with free nipples. Indeed, there is an unfair disparity among genders in this arena, though Playboy is historically culpable in this regard with its vast implications that femininity is connected to sexualization and commodification of the female body, which are distinctly postfeminist ideals.

Fundamentally, Byrne's essay highlights the individualized choice of her own empowerment in the feminist discussion, boiling her feminism down to the difference between a male and a female body on a magazine cover. In a truly postfeminist manner, as Gill describes, this trivializes and individualizes feminism for Byrne, a celebrity who has likely experienced few hardships from (for instance) the wage gap struggles, abortion access debates, and sexual assault policies that are real feminist issues that real women are facing. Byrne's attempt to brand herself as a contemporary feminist fails. She makes a statement only "in a way that does not necessarily pose any kind of challenge to existing social relations" (Gill, 2016, p. 619).

Byrne's attempt to brand herself as a contemporary feminist fails

As much as the young and old Hefners claim, Playboy’s message to the greater world has never been so simple as promoting “healthy conversation about sex.” Regardless of the purported intentions of the magazine, the reality is that the brand’s identity is synonymous with problematic objectification of women. The young Hefner and his fiancée may have better opted to pen essays that address or condemn this history, perhaps, or to use their celebrity status to open a conversation on consent in sexual interactions.

The resurgence of discussion of feminism in media has additionally coincided with a resurgence in misogyny. These ideas exist in relation and in tension with each other, signaling a crisis of gender roles in society. In the United States, for example, the last president ended his tenure by publishing an essay in which he encourages feminism whereas the current POTUS was caught on record bragging about sexually assaulting women. Not coincidentally, the latter has historically had a close relationship with the Playboy brand, including being featured in Playboy Magazine, appearing in a Playboy-associated softcore pornographic film, and frequenting Playboy's infamously sexist parties.

Cooper Hefner has made attempts to distance himself and the Playboy brand from the current POTUS, but to really come into the feminist discussion, as he claims , Hefner must take much more drastic steps away from his father's connections to misogyny. Rather than continue to try to convince people that feminism means posing nude for a magazine which has long been connected to the objectification of women and problematic gender roles, Playboy and Hefner should open their pages to real debates about feminism, address the rise in misogyny, and actually do what they’ve always claimed to do: foster healthy conversations about sex; this means all sex, not just sex for the privileged and pretty.

More info on Playboy's postfeminism can be found here

References

Gill, R. (2007). Postfeminist media culture: Elements of a sensibility. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 10(2), 147-166. doi:10.1177/1367549407075898

Gill, R. (2016). Postpostfeminism?: New feminist visibilities in postfeminist times. Feminist Media Studies, 16(4), 610-630. doi:10.1080/14680777.2016.1193293