The Pearl River Delta: a region of copycats or a center of innovation?

Do you know the Pearl River Delta region? And what comes to mind when you read something about Chinese products? Probably images of cheap ‘made in China’ junk or low-quality or imitation products (copycats), manufactured in enormous factory halls in bad circumstances. That is not surprising, as indeed it is what most people think. But did you know that a region in China currently is investing billions in stimulating innovative companies? And that the city of Shenzhen within that region currently is becoming the hardware capital of the world? This particular region is called the Pearl River Delta.

Welcome to the fascinating Pearl River Delta region

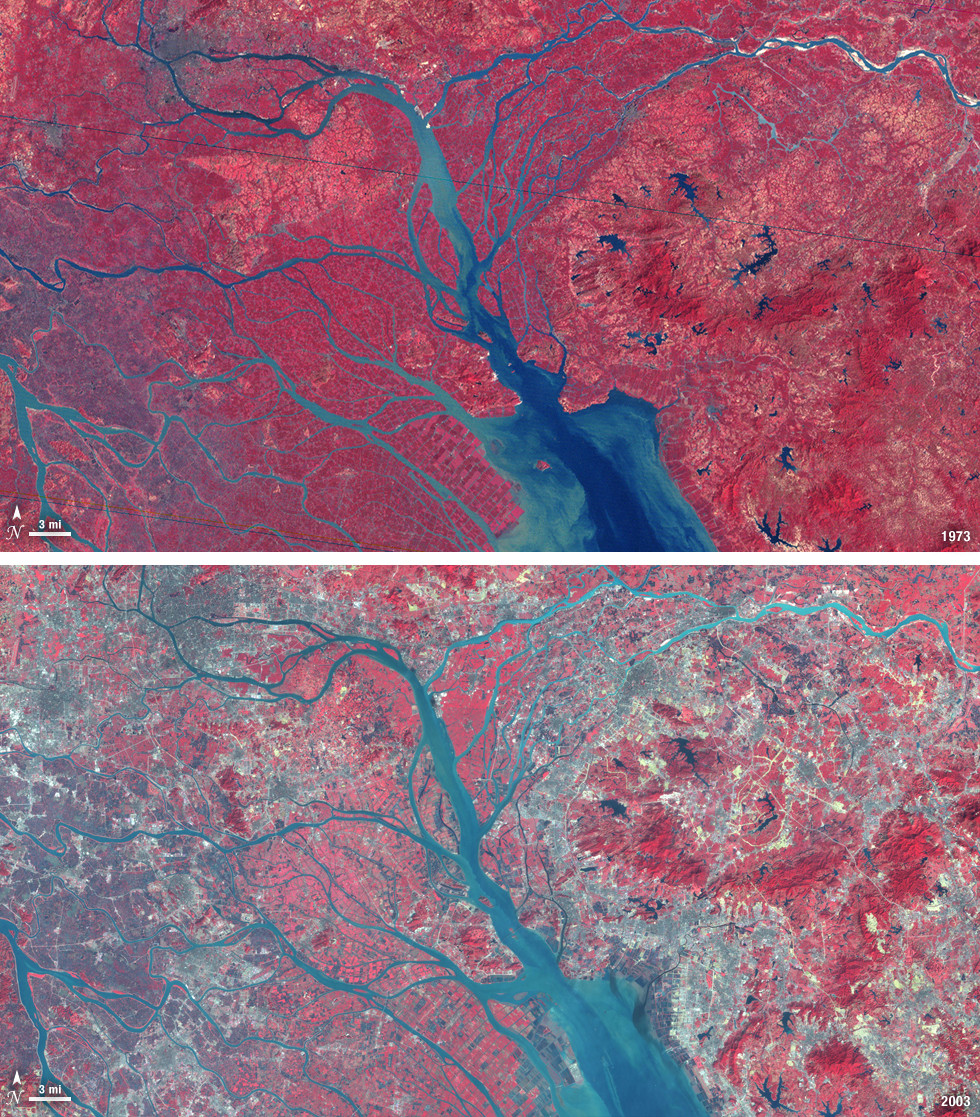

The Pearl River Delta (PRD) is a megacity located in the province of Guangdong in the south of China. The megacity consists of eleven heavily interconnected cities, all strategically based in an enormous river estuary that joins the South Chinese Sea. The eleven cities also comprise Special Administrative Regions (SARs) Hong Kong and Macau. These regions have their own, separate political and economic (capitalist) system but are to a large extent dependent on China and the PRD region (Hong Kong Trade Development Council, 2018).

Made in China.jpg

Cheap ‘made in China’ junk or low-quality or imitation products (copycats), manufactured in enormous factory halls in bad circumstances

According to British newspaper The Guardian, the PRD took over Tokyo’s position as the largest urban area in the world, in both size and population, in January 2015. The PRD has an astonishing estimated population of 65 million people, which is comparable to the entire population of the United Kingdom, all within a space as big as Croatia (The Guardian, 2015).

Since the 1980s, the PRD has developed into one of the most important economic centers of China and South East Asia, and it is still growing. While this important economic and commercial ‘motor of China’ is home to only 4.3% of the Chinese population, it has managed to become the generator of 9.1% of China’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This comes down to $1.2 trillion, comparable to the entire economy of Mexico. With an estimated nominal GDP per capita of $17,182, the PRD is one of the richest regions in China and also in the world (World Bank, 2015). The strategic economic position is also reflected in the massive export rates: 29% of China’s export originates in the PRD region (Geoshen, 2018).

A copycat imago

The PRD has acquired economic status as the ‘factory of the world’ and a reputation as a ‘center of copycats’ (South China Morning Post, 2017). The term ‘copycat’ refers to ‘products that have been designed, branded or packaged to look exactly like that of a well-established competitor (often a product from the western world), and it is usually cheap imitation’ (Monash University, 2018). Countless companies are suing Chinese companies or plagiarism, copying their product, or, even worse, business espionage and attempts to gain information by hacking.

The Gross Domestic Product of the PRD comes down to $1.2 trillion, comparable to the entire economy of Mexico

Today, the PRD is still developing rapidly, and not only ‘copycats’ but also an increasing number of innovative companies and start-ups, especially within the hardware and automotive sectors, are based in the PRD (The Economist, 2017). So, the question is, is it fair that the PRD is still seen as a center of copycats and not as an important center of innovation? This article aims to find the answer to this question as well as factors that might have had an important effect on this transformation. Immanuel Wallerstein’s World-systems analysis is used as an important guide throughout the article.

How did The Pearl River Delta region develop into the ‘’factory of the world’’?

In order to investigate if the PRD has become a center of innovation or one of copycats, it is essential to understand how the region originated and how it developed into an incredibly productive area nicknamed the ‘’factory of the world’’ (South China Morning Post, 2017).

Before the economic reforms in China and the opening of several economic zones to the rest of the world in 1979, the PRD region was struggling with poverty and the economy was mainly based on fishing and agriculture (Geoshen, 2018). In terms of Wallerstein’s world-system analysis, the PRD would have been classified as a periphery, mainly active in producing primary materials, with low surpluses and minimal profits (Wallerstein, 2004).

After the Second World War, China also had to deal with huge losses, political instability, and economic damage, which caused a destructive crisis. In those turbulent times, the region was sparsely populated, and the vast majority of people, often poorly educated, lived in the countryside. Only 28% of the population lived in cities, mainly in Guangzhou (Geoshen, 2018).

Before the 80s, there was no such thing as a modern industry in the region and the infrastructure connecting the area with other parts of China was of very poor quality, which was not conducive to trade. Nevertheless, the location in the delta of several rivers is strategically valuable, and the Chinese government had big plans for the region. Hong Kong and Macao had been under the influence of the United Kingdom and Portugal respectively for a long time and already had a good infrastructure and a stable economy (MacauHub, 2017).

It was no surprise that the PRD was chosen as a Special Economic Zone, since it was traditionally known as China’s gateway to the world

In 1979, the Chinese Communist Party began to re-organize and open its economy in a controlled way, by selecting several so-called Special Economic Zones (SEZs). Those SEZs are free-market-oriented zones on strategic locations with several favorable benefits intended to stimulate the economy. The PRD was chosen as one of those rare SEZs, together with Xiamen, Zhuhai, and Shantou (several other regions would follow). These areas were selected and created by China’s former leader of the communist party, Deng Xiaoping, as a part of economic reforms intended to modernize China.

It was no surprise that the PRD was chosen as a SEZ, since it was traditionally known as China’s gateway to the world. For a long time, Hong Kong had been a British enclave and Macao had been a Portuguese stronghold, and several other western superpowers tried to take over the area. In addition, the region could benefit from the ‘free ports’ and the already existing infrastructure in Macao and Hong Kong (Breznitz, 2014). The economic shift soon turned out to be a real economic success.

Because of the new regulations of the PRD, the region had a huge pull effect on migrant workers and global, regional, and local businesses. The new tax and business incentives were very attractive and favorable for Western multinationals, and cheap labor and low real estate prices ensured that many companies invested in the region. The PRD received an estimated share of 30% of all foreign investments in China (Geoshen, 2018).

Western companies started to build many factories, machines, and warehouses in the area, and, subsequently, the region transformed from an agricultural zone into one huge factory (Thomas Chan, 2017). The enormous number of factories and companies entailed an immense supply of jobs. The region became a very popular destination for millions of migrant workers from the relatively poor Chinese mainland. As a result, the PRD's population grew explosively, and the villages transformed into cities (Geoshen, 2018).

pearl-river-delta-infrastructure-for-china-megacity_02.jpeg

Due to the free-market-stimulating regulations implemented by the government, the PRD developed from a periphery into an economic center on a regional scale and a semi-periphery on a global scale (Breznitz, 2014). The region transformed into an industrial powerhouse within a large transit economy, mainly focused on the manufacturing and production of semi-finished products on a large scale (e.g. garments, toys, and textiles), with a moderate surplus (Wallerstein, 2004). In this stage, the PRD reached its infamous economic status as the factory of the world.

The common perception of the PRD became that it was unable to create innovative products and services

Numerous countries and companies labeled China and the region as copycats because of the fact that the factories in the PRD were mainly active in manufacturing products that has been designed, branded, or packaged to look exactly like that of a well-established competitor, and often are cheap imitations (South China Morning Post, 2017).

The common perception of the PRD became that it was unable to create innovative products and services. This is a very characteristic point in the development of the PRD, because in this stage the region had developed into an important economic center within China but was still at the margin of the world’s economy. The region remained in this stage for a long time. It is still struggling to take the step towards becoming a global center focusing on high-tech product innovation, finishing, and marketing leading to a high surplus (Wallerstein, 2004).

Interesting developments and transitions in the Pearl River Delta

The continuing economic growth of the PRD, uninterrupted since the 80s, has resulted in major changes in the area. A couple of those changes have had large effects on the PRD's attempts to transform from a semi-periphery into a center.

The Chinese government, the governments of the SARs, and several stakeholders are investing heavily in large-scale infrastructure projects in order to integrate the region to improve efficiency. The aim is not only to increase the connection between the eleven cities within the PRD and the export channels, but also to improve the connection between the PRD and mainland China.

The current infrastructure is already better than that of many other developing countries

The latest five-year plan calls for the creation of a "one-hour transport circle" to link the main cities in the PRD. As such, this plan reveals the importance of the infrastructure and the ambition of the PRD (Fuller, 2017). The infrastructure investments are expected to increase the accessible pool of consumers and workers, stimulate the accumulation of knowledge and human capital, and reduce the transportation costs (Geoshen, 2018). The investments are beginning to bear fruit, because export as a share of Guangdong’s industrial output is increasing rapidly.

Hong Kong - Macao Bridge.jpg

China can count on the participation of the SARs in its new integration plans, since the economic growth of Hong Kong is stagnating and Macau is simply too small and populous to expand, so both are forced to cooperate with other cities and invest in infrastructure (Thomas Chan, 2017).

The current infrastructure is already better than that of many other developing countries, but the shape of the coastlines and rivers in the estuary makes it difficult to reach some corners of the region. An iconic example of such an infrastructure project is the brand-new Hong Kong – Zhuhai – Macao bridge, which opened in 2018. The bridge is 55 kilometers long and reduces a four-hour journey from Hong Kong to Macao to a comfortable 40-minute drive. The estimated cost of the project is $7.56 billion (CNN, 2018).

Economist Richard Baldwin in his book The Great Convergence argues that most of the time in the industrial era the firm-specific know-how and knowledge-sharing culture remained in the factories and among people of the western world (Baldwin, 2017). This knowledge gap is resulting in an emerging divergence between the human capital of the West and that of the rest of the world.

As already mentioned above, after 1980, western multinationals started to build factories in foreign countries, such as China, in order to benefit from cheap labor, but knowledge remained in the West. China could barely benefit from new knowledge. Even today, the PRD is struggling with the tenacious knowledge gap withthe western world. In order to solve this problem and narrow the knowledge gap in technology, the Chinese government and factories in the PRD are investing billions in research and development (Wong, 2016). But still the PRD is lagging far behind Western countries when it comes to knowledge about technology.

Due to the unstoppable economic growth of the PRD, the wages of the population are increasing heavily. The nominal GDP per capita in the PRD is estimated at $20,000 (CNN, 2018). This means that, if the PRD was a country, it would be one of the richest nations in the world. China as a whole is ranked much lower, which reveals the huge gap between the PRD and the rest of China.

If the Pearl River Delta was a country, it would be one of the richest nations in the world

Companies used to come to the PRD for cheap labor, but as the region has developed into a wealthy area, that has changed. As a result of increased salaries, factories are forced to find alternatives to save money. As a result of the fact that labor is getting more expensive, the mission for companies and factories in China, and especially in the PRD, is to upgrade the manufacturing process through automation in order to cut back costs. It is simple: to eliminate jobs, the factories have to look for cheaper solutions, like robots or smart manufacturing machines.

Currently, the level of automation in Chinese companies and factories remains low compared to its competitors', but companies in the PRD are investing large sums of money in automated factories and innovative methods to make the manufacturing process more efficient. The province of Guangdong, for example, spent more than 900 billion to boost the manufacturing and adoption of robotics in the province because they urgently need to increase productivity.

In the past, Chinese factory bosses never paid attention to efficiency, effectivity, or quality of processes. They had rather assigned more personnel to a certain task than invest in a solution such as simple automation, but this mindset is changing fast. Today, a large number of factory owners uncritically replace humans with robotics hardware in order to enhance productivity.

The Pearl River Delta: a region of copycats or a center of innovation?

China and especially the PRD are still struggling with their negative image of being copycats and unable to create innovate products and services, but they have proven that this perception needs thorough re-examination. In the past decade, the PRD has shown that the label of a region of copycats only is too simplistic.

In the past century, more countries have been faced with a struggle similar to China's. For a long time, Japan and the Republic of Korea were struggling with common perceptions that they were just simple imitators and unable to build up an innovative economy and develop new products. But, over the years, the countries have turned out to be very innovative.

Innovative companies like Samsung, LG, and Hyundai are established and based in the Republic of Korea, and companies like Xenoma and Dropbox are Japanese. Japan is also a leading country in the robotics industry. Those countries proved that it is possible to move from a copycat phase into an innovative phase, shifting from a semi-periphery into a center (Wallerstein, 2004).

Shenzhen now.jpg

“Shenzhen? Shenzhen is nothing but a manufacturing center, not a place to do research & development”

The PRD is outpacing the rest of China and severalother Western countries in its economic growth rates and investments in innovation (Fuller, 2017). For years, the region has been investing huge amounts of its GDP into research and development in order to stimulate this process and this is bearing fruit (The Economist, 2017), because the entire PRD region is currently transforming into an advanced manufacturing ecosystem with clusters of factories working symbiotically to turn the area into a one-stop show for many hi-tech and innovation projects (South China Morning Post, 2017).

New start-ups and entrepreneurs are increasingly interested in changing the region into an advanced and innovative manufacturing cluster with internal competition. In terms of Wallerstein’s world-system analysis, the PRD is currently shifting from a semi-periphery towards a global center., with a focus on high-tech product innovation, finishing, and marketing leading to a high surplus (Wallerstein, 2004). The economy has shifted its focus from labor-intensive and high-energy manufacturing processes to high-tech sectors, like telecommunications, fin-tech, and biomedicine (Fuller, 2017). Products have turned from being ‘made in China’ into ‘created in China’.

Products have turned from being ‘made in China’ into ‘created in China’

The best example to convince the world that the PRD is able to create innovate products and services, is the city of Shenzhen. The following quote, taken from an interview in the book The Run of the Red Queen (Breznitz, 2014), neatly captures how the world thinks of the PRD: “Shenzhen? Shenzhen is nothing but a manufacturing center, not a place to do R&D”.

But the PRD has not stood still. After years of investments in research and development, Shenzhen recently became the capital of the world for hardware entrepreneurs and transformed itself into one of the most attracting places for innovative start-ups. Nowadays, many entrepreneurs and firms active in the hardware industry, like Huawei and Tencent, which produce their own hardware and software, are founded and based in the PRD. Even Apple is currently building a research and development center in Shenzhen. This shows the ambition of the region to become a knowledge center (The Economist, 2017).

Pearl River Delta: copycats and innovators

This article clearly shows that China, and especially the PRD, with cities like Shenzhen and Guangzhou, is indeed able to innovate. But it is still quite hard to determine whether the PRD region is an innovative center or a center of copycats, because among the emerging number of innovative startups in the high-tech and automotive sector, there is still a large number of companies and factories that apply the business model of copying and imitating other products.

The answer to the question "is it fair that the PRD is still seen as the factory of the world or a center of copycats and not as an important center of innovation?" is a clear no. Currently, the PRD is shifting from a manufacturing semi-periphery towards a global center (Wallerstein, 2004). In this transitional phase, there is no clear side yet, as the innovators exist alongside the copycats.

References

Baldwin, R. (2017). The Great Convergence: Information Technology and the New Globalization. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Breznitz, D. &. (2014). Run of the Red Queen: Government, innovation, globalization, and economic growth in China. New Haven: Yale University Press.

CNN. (2018). The $20 billion 'umbilical cord': China unveils the world's longest sea-crossing bridge. Retrieved from https://edition.cnn.com/2018/05/04/asia/hong-kong-zhuhai-macau-bridge/in.

The Economist. (2017). Shenzhen is a hothouse of innovation. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/special-report/2017/04/08/shenzhen-is-a-hothou...

Enright, M. J., Scott, E. E., Petty, R., Enright, Scott & Associates, & Hong Kong (China). (2010). The Greater Pearl River Delta.

Fu, W. (2016). Towards a Dynamic Regional Innovation System: Investigation into the Electronics Industry in the Pearl River Delta, China. NY: Springer-Verlag GmbH.

Fuller, E. (2017). China's Crown Jewel: The Pearl River Delta. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/edfuller/2017/10/02/chinas-crown-jewel-the-....

Geoshen. (2018). Explore the Pearl River Delta megalopolis. Retrieved from https://geoshen.com/posts/the-pearl-river-delta-megalopolis

Griffiths, J., & Lazarus, S. (2018). World's longest sea-crossing bridge opens between Hong Kong and China. Retrieved from https://edition.cnn.com/2018/10/21/world/hong-kong-zhuhai-macau-bridge-i...

Hong Kong Trade Development Council. (2018). PRD Economic Profile | HKTDC. Retrieved from http://china-trade-research.hktdc.com/business-news/article/Facts-and-Fi...

Lin, G. C. (2014). Red Capitalism in South China: Growth and Development ofthe Pearl River Delta. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

MacaoHub. (2017). The Pearl River Delta enters a new era. Retrieved from https://macauhub.com.mo/feature/the-pearl-river-delta-enters-a-new-era/

Mack, L. (2017). Special Economic Zones in China. Retrieved from https://www.thoughtco.com/chinas-special-economic-zones-sez-687417

Monash University. (2018). Marketing dictionary - Copycat Product. Retrieved from https://www.monash.edu/business/marketing/marketing-dictionary/c/copycat...

Mozur, P. (2014). Chinese Gadgets Signal New Era of Innovation. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinese-gadgets-signal-new-era-of-innovatio...

South China Morning Post. (2017). China's 'copycat? tech companies now the ones to beat. Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/comment/insight-opinion/article/2083377/how-chinas-...

South China Morning Post. (2018). Hi-Tech in Shenzhen. Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/topics/hi-tech-shenzhen

Van Mead, N. (2015). China's Pearl River Delta overtakes Tokyo as world's largest megacity. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/jan/28/china-pearl-river-delta-o...

Van Mead, N., & Hilaire, E. (2016). The great leap upward: China's Pearl River Delta, then and now. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/may/10/china-pearl-river-delta-t...

Thomas Chan, L. d. (2017). Pearl River Delta - From Factory of the World to Global Innovator. Macao: International Institute of Macao.

Wallerstein, I. (2004). World-systems analysis: an introduction. Durham, North Carolina, United States of America: Duke University Press.

We Build Value Magazine. (2017). Pearl River Delta: China’s Megacity - Salini Impregilo Digital Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.webuildvalue.com/en/reportage/pearl-river-delta-infrastructu...

Wong, P. (2015). How China's Pearl River Delta went from the world's factory floor to a hi-tech hub. Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/comment/insight-opinion/article/1864553/how-chinas-...

Wong, J. (2016). How China is fast narrowing the technology gap with the West. Retrieved from https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/how-china-is-fast-narrowing-the-tec...