An intimacy coordinator on the film set: an unnecessary luxury?

The appearance of intimacy coordinators on film sets is one concrete effect of the #MeToo movement. After the movement appeared in 2017, many organisations have been trying to improve their workplace culture. The #MeToo movement's fight against sexual harassment and sexual assault became most visible with the case of Harvey Weinstein. The American film producer received sexual harassment allegations from over 80 women. His case was especially focused on the abuse of power relations for sexual gratification.

Cases such as Weinstein's call for changes in the workplace culture in the film and television industries. In America, HBO and Netflix for instance recently started making use of an intimacy coordinator to guide their actors through sex or intimate scenes. BBC is also employing intimacy coordinators. This concept can be seen as a good start in efforts to reduce cases of sexual harassment involving the power relation between directors and actors on film sets.

In the Netherlands, directors and actors are still sceptical about the role of such a coordinator even though movies produced in the country are well known for their explicit nudity and sex scenes. This paper therefore focuses on the question of whether the use of intimacy coordinators would be beneficial within the Dutch film industry. Examining the #MeToo movement, the film industry and Dutch films with explicit nudity and sex scenes from a feminist perspective will help bring forward the different benefits and disadvantages of using intimacy coordinators also in the Netherlands.

Relation to the #MeToo movement

HBO was the first company to employ an intimacy coordinator after actress Emily Meade, who then played a porn star in the series The Deuce, spoke up. “When there are children or animals in a scene, there is always someone on set to protect and guide them through the scenes. But when it comes to sex, one of the most vulnerable matters for actors, there is no system”, she argued (van der Velden, 2019). This strong argument was convincing enough for HBO, who started always including an intimacy coordinator on film sets.

The popular Netflix series Sex Education followed next. Since the series is all about sex and intimacy, employing an intimacy coordinator seems logical. An actress in the series, Emma Macky, is very positive about the use of such a coordinator. In her case, the intimacy coordinator designed a real choreography for the sex scenes and they timed every action (van der Velden, 2019). Not only were the actors enthusiastic, but the director, Ben Taylor, also stated that it was “this initial breaking down of taboos that was most valuable, as well as the open discussion of sex scenes” (Sebag-Montefiore, 2019). The presence of the coordinator is aimed to help both actors and actresses, but especially actresses. In relation to the #MeToo discussion, a coordinator is seen as a good provision to help actresses feel safe and prevent cases of abuse.

"When it comes to sex, one of the most vulnerable matters for actors, there is no system"

The #MeToo campaign was originally started in 2006 by Tarana Burke, who had heard multiple reports of sexual violence in her work with girls in the context of a nonprofit organization she had co-founded, Just Be, Inc. "When #MeToo came into new prominence, more and more Americans shared their own stories of being harassed or assaulted in the workplace by people — most of them men — in positions of power" (North, 2018). The movement attracted a lot of attention and followers thanks to the online social media platform of Twitter. People could easily tell their stories with the use of the hashtag, thereby rendering them an important statement and a great example of online activism. According to Rivers (2017), “[a]s online spaces become thoroughly embedded in our offline lives the distinction between the two blurs, undermining the suggestion that a swell of online activism can have no substantial effect in ‘real’-world politics.”

In the case of #MeToo, these effects are becoming clearly visible. Harassers are being acknowledged and even prosecuted. However, results can also often be disappointing. In some cases, powerful men deny their actions and the prosecutors are left helpless. Therefore, it might be better to prevent such situations from arising, and using intimacy coordinators could be one strategy to achieve that.

Power relations at the film set

Most of the stories that surfaced with #MeToo were about harassment and assaults in the workplace by people in positions of power. We can think of many examples - Harvey Weinstein, Donald Trump, Silvio Berlusconi, Kevin Spacey and R. Kelly. All of them used their power to dominate and abuse women. This is also the case in the film industry, where the director has power over the actors. “Many actors feel that they have no choice but to go along with a director’s instructions, particularly in an industry rife with power imbalance and celebrity worship” (Sebag-Montefiore, 2019).

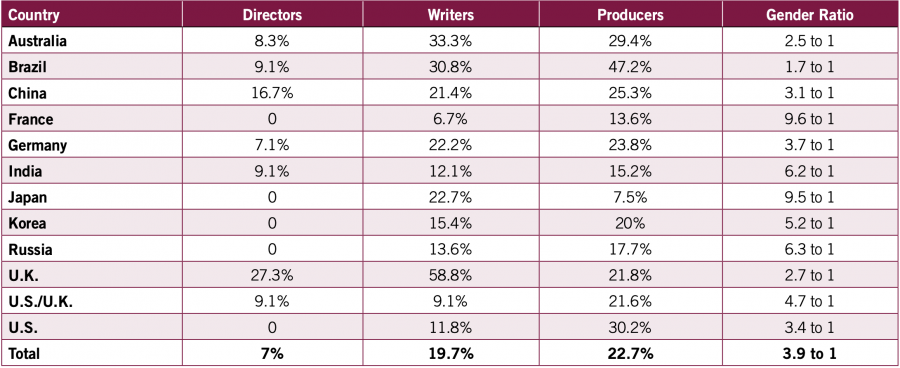

Table 1 Gender Prevalence Behind the Camera by Country

For example, "British actress Thandie Newton was promised being pictured from her shoulders up but it happened to be from her waist. And one producer demanded that she went topless and said: 'Listen sweetie, take off your shirt, audience ratings!' When she refused, another actor suddenly pulled her shirt off. She mentioned swear" (Zwol, 2018). This is a clear example of the power that directors have over actors. If an actor refuses to do what they're asked to do, they can be fired or simply replaced by someone else. An intimacy coordinator can help actors and directors reach solid agreements on what they would be willing to do and what not. Also, this coordinator can make sure these agreements are respected. Another important aspect to point out is that directors are mostly men. A relevant study found that “[o]ut of a total of 1452 filmmakers with an identifiable gender, 20.5% were female and 79.5% were male. Females comprised 7% of directors across the sample” (Smith, Choueiti, & Pieper, 2014a). The table above (Smith et al., 2014b) shows the distribution in the eleven different countries that were part of the study. While China and the UK had respectively 16.7 and 27.3 percent female directors, the other countries could not even reach 10%. The Netherlands was not examined in this study, but it can be seen as comparable to countries such as Germany and France.

"Many actors feel that they have no choice but to go along with a director’s instructions, particularly in an industry rife with power imbalance and celebrity worship"

This lack of female directors can be problematic for actresses who have to do sex scenes. Actresses might feel safer in a sex or nudity scene when female crew members are around. Actress Roberta Colindrez (known from the TV series I Love Dick) explains: “Knowing that the entire camera department, except for the DP [Director of Photography], was female, for me, meant complete freedom and safety and honesty about where all of this is coming from. It’s other women who can expose that female gaze honestly and with the most vulnerability without it being anything other than what it truly is. It’s the most honest cinema I think I’ve ever been in” (Fernandez, 2017).

At least for the time being, given the existing gender gaps it seems unrealistic to expect to have a large number of female crew members on every movie or TV set. It can therefore be very helpful to consider using an intimacy coordinator who can help establish trust and comfort for everyone on set.

Resistance from directors

Directors want to be powerful, it is part of their jobs. They do not want someone else to decide what a sex scene is going to be like. Directors have artistic responsibilities while intimacy coordinators are focused on ethical aspects of filmmaking. Sometimes, directors want to do a scene by intuition rather than rehearsing it. A long-standing criticism against over-rehearsing sex scenes has been that it leads to a loss of chemistry. Bernardo Bertolucci, who directed Last Tango in Paris (1972) once defended the film’s rape scene by arguing that he had wanted Ms. Schneider “to feel, not to act, the rage and humiliation” (Sebag-Montefiore, 2019). He only told the actress what was going to happen in the scene just before filming it.

From an ethical point of view, this is of course totally wrong. Directors work with humans who have feelings and this should be taken into consideration by those in this important, powerful profession. Human beings are not something that should be experimented with in such a way. It is still possible to direct art while taking this into account; all that is needed is good actors. When important things like the director's expectations regarding the content of a sex scene are not communicated, a trust issue arises. It is very important that actors and directors can trust each other. Directors often assume that this trust is already there and that there is no need for someone like an intimacy director.

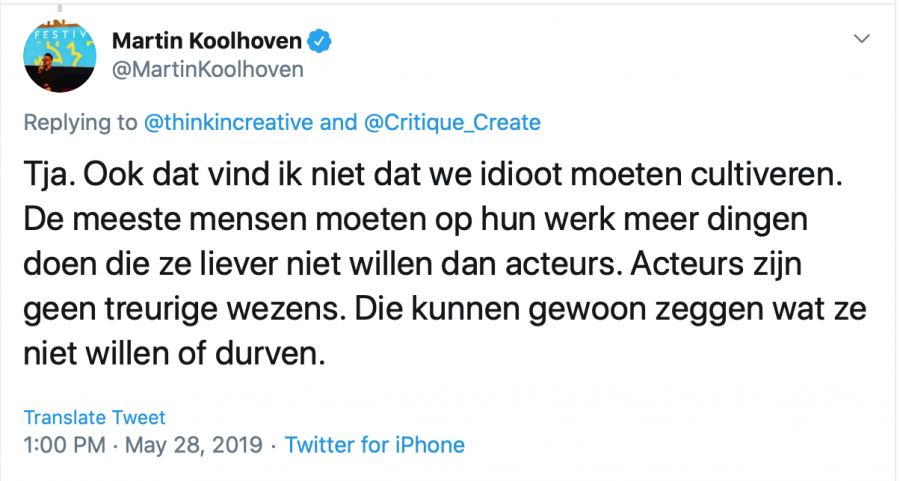

On the other hand, actors also play an important part in this. As director Martin Koolhoven put it on Twitter: “They [actors] can just tell what they do not want or dare”. When reading the script, actors can indicate what they would not be willing to do. However, it is better to make such things known before casting someone for the role. Then the director can still search for another actor who does not have problems with the planned scenes. Another thing that Koolhoven (personal communication on Twitter, May 28, 2019) mentioned to me was that it is okay for actors to feel uncomfortable. However, what counts as uncomfortable can be different for every person. He does not think this is a problem. Dutch actors are very cooperative in general and it is the director's job to guide the actors through difficult scenes, as he further explained. Even though he was sceptical about the idea of an intimacy coordinator, he admitted that someone like that could help on the set.

Similarly to a stunt coordinator coordinating fight scenes, an intimacy coordinator could bring the necessary expertise to improve things. An important point made by Koolhoven was that employing a coordinator should not cost a lot, considering the need for one also in small-budget films. According to Koolhoven, someone who is constantly on set acting like a police officer is unnecessary, not needed and expensive. (Koolhoven, personal communication on Twitter, May 28, 2019)

Explicit female nudity in Dutch films

Another aspect to mention is that nudity in films is, most of the time, female nudity. “Female characters continue to be sexualized to a greater degree than their male counterparts. Among the 100 top-grossing films in 2014, women are nearly three times as likely as men to appear partially or fully nude in movies (26% and 9%, respectively)” (St. Mary’s University, 2016). Seeing female breasts on the screen is not a surprise anymore while penises are hardly ever seen. Women are stereotypically seen as sexy, hot and prone to being objectified as a sex object. But, all things considered, sex still sells. Films containing explicit sex or nudity scenes get a lot of media attention for them. Media coverage is key in constructing audience opinions. The audience's prior knowledge that a film will contain female nudity might influence their decision to watch it or not.

Unlike female nudity in films, male nudity is not very popular with directors also because, as we have seen, most directors are (heterosexual) men. “The idea of male nudity, regardless of romantic context, is still shied away from by male directors in favor of the more palatable appearance of straight females.” (Lopez, 2018)

The Netherlands is a good example of a country that is accustomed to having a lot of female nudity on the screen. Just think of examples such as Turkish Delight (1973), Black Book (2006), Flodder (1986) and Komt Een Vrouw Bij De Dokter (2009). In the early seventies, explicit nudity became a trend in Dutch films. Dutch director Paul Verhoeven is the most well known for the explicit nudity in his films. He mentioned that the trend was related “to the sexual freedom common in Amsterdam.” (van Heezik, 2015). However, this does not explain the prevalence of female nudity in other countries' productions.

In the United States, for instance, Turkish Delight was considered pornography, and there was also a lot of resistance towards the film in France too. The film was based on the similarly titled book by Jan Wolkers (1969) which focused on a boy and a girl falling in love with sex being just a part of the story. Turkish Delight was a remarkable film because it broke a lot of taboos. People may only remember the sex scenes because they really stood out at the time. However, the sex scenes were more playful than pornographic. As Paul Verhoeven mentions: “We, in the Netherlands, do not have a culture of making things more beautiful than they are or hiding them" (van Heezik, 2015).

"Because of the rise of aids, sex lost its innocence; it was dangerous."

When we think about the history of nudity in Dutch films, we might conclude that the Netherlands is not very afraid of showing nudity. However, this was only the case in the seventies. "In the early eighties this changed. Because of the rise of aids, sex lost its innocence; it was dangerous. The feminists at that time thought that the female bodies were made into an object and therefore did not like all the nudity. Also, the rise of pornography caused a lot of resistance" (Rusman, 2018). With the #MeToo discussion, this fear is even bigger. Also other aspects, such as the idea that 'sex sells' as sole motivation for nudity, can make women refuse to go naked.

A lot of women in the Netherlands are okay with nudity on the film set, however. Think of the Dutch actresses who are known for always appearing nude in their films. Like Carice van Houten, now famous for her role in Game of Thrones. Her butt is the most seen butt in Dutch movies. Halina Reijn is also not someone to shy away from appearing naked in her films. Still, there are many actresses that are not comfortable with nudity. And Dutch culture appears to be pushing actors towards this direction of "just doing" such uncomofortable scenes. An intimacy coordinator could help change this by providing more comfort for actresses.

Intimacy coordinator: a great tool for safety

The #MeToo movement stands for a better work environment (especially) for women. Sexual abuse and harassment take place in almost every workplace and many organisations are trying to prevent such abuse. Most sexual harassment has to do with power relations, as is also the case in the film industry. Directors have power over the actors, which can lead to cases of abuse. An intimacy coordinator can contribute to the creation of a more trusting and safer film set.

Netflix already employed an intimacy coordinator and the reactions to that were very positive. Because of the presence of a coordinator, sex and nudity scenes are more choreographed, which makes the process more comfortable for the actors. However, there is still resistance from directors, who want to stay in charge. They may argue that if the actors do not want to do something, they can just tell that to the director. Trust and transparency are indeed very important in the relationship between director and actor. But actors often feel overpowered, shamed or think they might be overreacting. This may cause them to keep silent about their fears, shame and negative feelings.

Because there is mostly female nudity in films, this is also a feminist issue. The lack of female directors also makes the issue difficult for actresses. In the context of the Netherlands, although the Dutch in general might be tolerant towards sex and nudity in films, there are of course still a lot of actors that have their own personal boundaries. These actors might be pushed by the film culture to do types of acting that are uncomfortable for them. Therefore, for a country like the Netherlands, it is especially good to make use of an intimacy coordinator. A recommendation for directors is to see if there are scenes that can be potentially harmful for their actors and discuss this with their crew. Transparency and trust are the cornerstones of any good professional relationship. If there are any doubts, an intimacy coordinator can be employed to bring expertise. At the same time, this coordinator has to make sure he/she does not interfere by policing the artwork. All in all, the use of an intimacy coordinator is not an unnecessary luxury but a tool for making sure that your actors feel safe at work.

References

Amanda Blumenthal. (n.d.). Intimacy Coordinator for Film and Television.

Fernandez, M. E. (2017, May 24). What Happens to Nudity Onscreen When You Remove the Male Gaze?

Heezik, van C. (2015, September 15). Nederlands naakt.

Lopez, K. (2018, May 2). A Matter of Legitimacy: Female Nudity On-screen | Balder and Dash | Roger Ebert.

North, A. (2018, October 11). Brett Kavanaugh, Harvey Weinstein, and the evolution of #MeToo.

Rivers, N. (2017). New Media, New Feminism? Postfeminism(s) and the Arrival of the Fourth Wave, 107–131.

Rusman, F. (2018, June 8). Alleen de jaren 70 waren níet preuts.

Schiraldi, P. (2019, May 16). HBO to Staff All Sex Scenes With Intimacy Coordinator.

Sebag-Montefiore, C. (2019, January 23). How to Make Sex Scenes Natural and Nonthreatening? Cue the Intimacy Coordinator.

Smith, S. L., Choueiti, M., & Pieper, K. (2014a). Gender Bias without Borders: An Investigation of Female Characters in Popular Films Across 11 Countries.

Smith, S. L., Choueiti, M., & Pieper, K. (2014b). Table 2 Gender Prevalence Behind the Camera by Country. Table.

St. Mary’s University. (2016). The Report on the Status of Women and Girls in CaliforniaTM (5).

Velden, van der I. (2019, March 20). Choreografie voor seksscènes: de opkomst van de intimiteitscoördinator.

Woods, S. (2018, September 8). The Last Word: David Simon on Twitter Trolls, Trump and Making ‘The Deuce’ in the #MeToo Era.

Zwol, van C. (2018, October 30). Intimiteit kan je coördineren.