Knives Out (2019) and the classical detective formula

This article will examine how director Rian Johnson created a satisfying detective fiction filled with twists and turns in Knives Out (2019). The film not only draws upon conventions within the classical detective genre but subverts the viewers’ expectations when engaging with classical detective stories. A plot analysis of the feature film will be conducted by following John G. Cawelti’s third formula of classical detective stories (characters and relationships).

Knives Out (2019)

Written and directed by Rian Johnson, Knives Out (2019) is an original detective/murder mystery film that tells the story surrounding the death of Harlan Thrombey, an established crime novelist (beware of spoilers if you have not seen the movie):

The day after his 85th birthday party, Harlan is found dead in his room with his throat slit. Private detective Benoit Blanc is hired for the investigation of Harlan’s death. As Blanc interviews members of the Thrombey family, it is discovered that many have had altercations with Harlan the night before his death: the patriarch fires his youngest son Walt from his publishing company, gives an ultimatum to Richard, his son-in-law, demanding him to come clean with his daughter Linda about his extramarital affairs, cuts off Joni’s allowance as he finds out that the daughter-in-law has been stealing from him, and engages in a heated argument with his grandson Ransom.

While it seems as though several members of the family have their motives for Harlan’s murder, it is subsequently revealed to us that Harlan slit his own throat in an attempt to fabricate a false alibi for Marta, his personal nurse, who has seemingly overdosed him with morphine accidentally and was unable to find the antidote, leaving him with only minutes to live. The plot thickens further upon the reading of Harlan’s will when it is announced that Marta will be the sole inheritor of his fortune. This leads to a struggle for Harlan’s fortune between the Thrombeys and Marta, all the while detective Blanc proceeds with his investigations amidst the chaos. It is eventually revealed that Ransom is the culprit, who, upon discovering that Harlan is leaving his inheritance to Marta, develops a plot to kill his grandfather and frame the murder on Marta so she will not be able to claim the inheritance owing to the slayer rule.

The film has received overwhelmingly positive responses from critics and audiences alike (receiving a 7.9/10 IMDb user rating and a 92% audience score along with a critically rated 97% on Tomatometer on Rotten Tomatoes). Among the positive reviews the movie has received, several of them made references to the classical detective fiction writer Agatha Christie, with one review even comparing Benoit Blanc, Knives Out’s leading detective, to Christie's renowned detective character Hercule Poirot.

The Formula of the Classical Detective Story

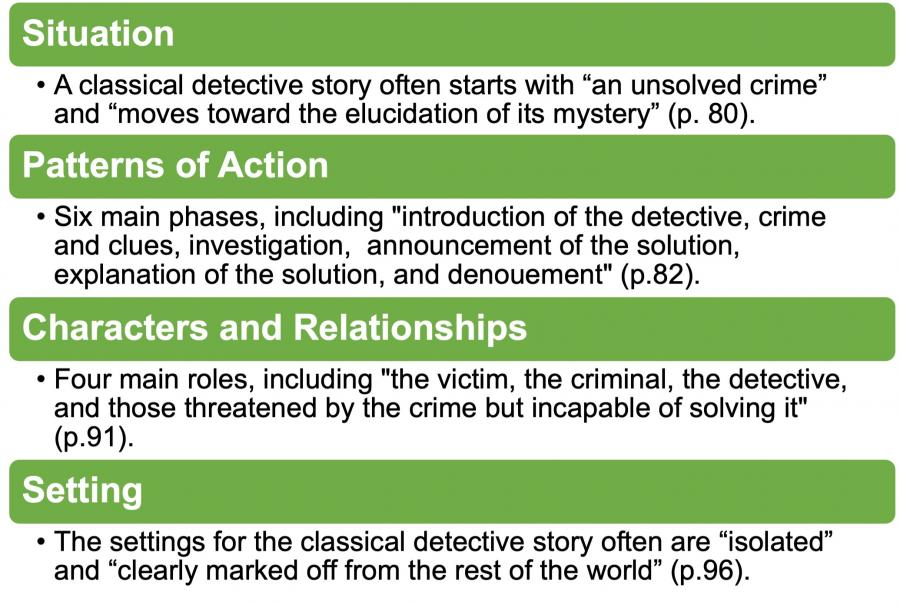

In the fourth chapter of Adventure, Mystery, and Romance (1976), John G. Cawelti charted out four formulas for the classical detective genre.

Cawelti’s four formula for classical detective stories (1976).

Most importantly in the case of Knives Out, Cawelti foregrounds the tensions the classical detective writer has to negotiate in his character design, and how the chosen authorial design may have effects on reader comprehension and identification. The scholar’s focus here synergizes well with the film, which presents an array of interesting characters with their own unique personalities and (sinister) motivations. In the following paragraphs, I will present a plot analysis of Knives Out following the four main roles (victim, criminal, detective, & those threatened by the crime but incapable of solving it) suggested in Cawelti’s third formula (characters and relationships).

The Victim

In characters and relationships, Cawelti marked the crucial balance the classical detective writers must strike when portraying the victim in their stories. As the scholar suggested, if “too much information is given about the victim or if he seems a character of great importance”, the writer runs the risk of pulling attention away from the process of investigation. Conversely, when hardly any information has been provided about the victim or he/she seems to be of little significance, “interest in the inquiry and suspense about its outcome will be minimal” (Cawelti, 1976, p.91).

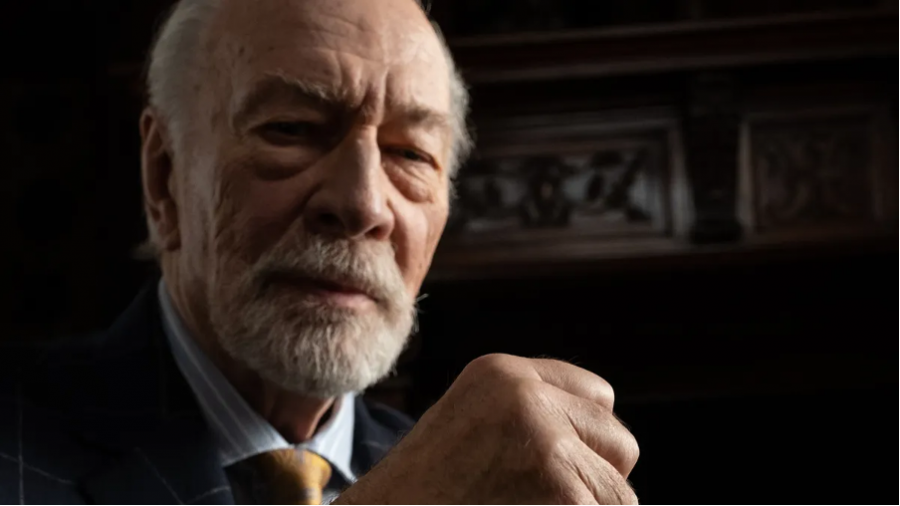

Still shot of Harlan Thrombey.

In Knives Out, such tension could be identified if we consider how scenes featuring the victim, Harlan Thrombey, are arranged in the film. During the first half of the film, director Rian Johnson does not seem to feel compelled to restrain Harlan; letting him shine completely in multiple scenes. This is made evident in several character flashback scenes in which the character, being the patriarch of the family, unapologetically informs various members of the family that he made the decision to cut them off financially. Harlan also takes the spotlight in the crucial scene where Marta, his personal nurse/close confidant, has seemingly injected him with a fatal dose of morphine. After realizing the mistake, Harlan carefully provides Marta with a detailed set of instructions before slitting his own throat so that she could potentially get away with his murder. In all of these scenes, the audience is shown a firm but caring patriarch whose death deserves our attention.

During the second half of the film, however, the patriarch Harlan Thrombey almost entirely disappears; the mysteries and the aftermath surrounding his death are instead put to the fore. One crucial sequence that marks this transition is the reading of the will scene that takes place around the middle of the film. In the scene, it is revealed that the recently deceased Harlan has left his entire inheritance to Marta, who has become one of his closest friends towards the end of his life. After this titular scene, the focus is shifted from the interaction between Harlan and other members of the Thrombey family to that between Marta and the Thrombeys. Namely, the latter would proceed to ceaselessly threaten the former to renounce the inheritance and use whatever means necessary to force the former to give up the fortune that they deem to be rightfully theirs.

As could be observed, Knives Out director Rian Johnson has to deal with the inherent tension when portraying the victim, much like other classical detective writers. On one end, the victim, crime novelist Harlan Thrombey, must be a man of significance so that the audience would be attentive to the investigation of his death. On the other end, Thrombey must not overshine and take over the investigation process itself, which is arguably the meat of the classical detective story. Johnson’s method of dealing with this tension is twofold. First, by initially building the victim character Harlan Thrombey through various flashback scenes, the audience starts to care about the investigation of his death. Second, by setting an organic fault line, i.e., the reading of Harlan’s will, the viewers’ attention is shifted towards Marta in the second half of the film, who has unexpectedly inherited Harlan’s fortune and who also happened to be at the center of Harlan’s mysterious death.

The Criminal

One important convention that Cawelti laid bare regarding the criminal is the notion of the least-likely person. As the scholar explained, the classical detective writer would often cast the true criminal in the shadows throughout the story so that little thought is given to him/her. This convention stems from the twofold necessity of preventing the reader from solving the crime prematurely and “keeping the person who is to become the embodiment of guilt on the sidelines” so that the reader would not develop misdirected feelings of sympathy for the criminal (Cawelti, 1976, p. 90, 93).

Still shot of Hugh Ransom Drysdale.

This least-likely person trope is strategically utilized in Knives Out. Towards the end of the film, detective Benoit Blanc finally reveals that the criminal in this case is Hugh Ransom Drysdale, the grandson of Harlan Thrombey. Hugh had switched Harlan’s drugs in hope that Marta would mistakenly inject a fatal dose of morphine that could kill his grandfather; this would in turn cause Marta to lose the inheritance because of the slayer rule. Noteworthily, unlike other members of the family, who have all been properly introduced to the audience during the initial police interrogation sequence, Ransom does not make a befitting entrance until the aforementioned reading of the will scene.

Director Rian Johnson masterfully plays with the convention of the least-likely person in Knives Out

Based on his absence in the first half of the film, it might be tempting for a keen detective reader aware of the least-likely person trope to draw the speculation that Ransom is the criminal mastermind in Knives Out. Nonetheless, suspicion was quickly driven away from Ransom in the second half of the film, as the character would obtain a much greater amount of screen time. Moreover, in the second half of the film, Ransom had formed an unlikely alliance with Marta. This alliance also has the potential to throw the audience off his trail of suspicion. Namely, as we have gradually associated ourselves with Marta, who has by the second half become the protagonist of the film, we cannot help but cast her ally Ransom in a positive light as well.

However, this understanding was turned on its head again in the final scene of revelation, as the audience learned that Ransom’s character development in the second half of the film turned out to be smoke and mirrors and that he was indeed the perpetrator of the heinous crime.

Director Rian Johnson masterfully plays with the convention of the least-likely person in Knives Out. Namely, he first draws the audience’s attention to Ransom, who arguably could be the criminal owing to his absence in the first half of the film. This signifies the least-likely-person-being-the-criminal tradition in classical detective stories. After the reading of the will scene, however, the audience notices a break in this initial understanding, observing that not only does Ransom become way more visible in the second half of the film but even formed an alliance with the protagonist. These function as red herrings, driving suspicion off Ransom. The final revelation shattered this secondary understanding, as it is eventually revealed that Ransom is indeed the criminal. Overall, via a carefully designed game of hide and seek where the criminal is at times being cast in the shadows and others in the spotlight, Johnson was able to constantly throw the audience off their feet and toy with their expectations.

The Detective

Cawelti also identified the detective as one of the titular characters in classical detective stories for their established role in the primary emphasis of such stories, i.e., the investigation of the crime (1976, p.93). For the scholar, the detective is “a brilliant and rather ambiguous figure who appears to have an almost magical power to expose and lay bare the deepest secrets”, and yet “he chooses to use these powers not to threaten but to amuse us and to relieve our tensions by exposing the guilt of a character with whom we have the most minimal ties of interest and sympathy” (Cawelti, 1976, p.94).

Benoit Blanc, Lieutenant Elliott, & Trooper Wagner.

Although conventional classical detective stories certainly do not shy away from asserting and celebrating the detective’s brilliant investigative powers, Johnson seems to be less willing to completely indulge in this fantasy when writing and directing Knives Out. On the one hand, Benoit Blanc is an unquestionably talented detective, as seen from his capacity to correctly deduce the various secrets the Thrombeys did not confess during the initial interrogations. For instance, Blanc is able to come to the accurate conclusion that Richard Drysdale, Ransom’s father and husband of Linda, the first daughter of Harlan Thrombey, was having an affair. The detective deduces this on the basis of the caterer overhearing Harlan exclaiming, “You tell her, or I will!” when Richard and the patriarch are having an argument in the study.

On the other hand, Blanc’s method of investigation is certainly different from those of the classical detectives who generally play an active role in the investigative process, e.g., Holmes and Dupin. As the detective himself has explained (Johnson, 2019, p.56):

Benoit Blanc: Harlan’s detectives, they dig, they rifle and root. Truffle pigs. I anticipate the terminus of Gravity’s Rainbow.

Marta Cabrera: Gravity’s Rainbow.

Benoit Blanc: It’s a novel.

Marta Cabrera: Yeah, I know. I haven’t read it though.

Benoit Blanc: Neither have I. Nobody has. But I like the title. It describes the path of a projectile determined by natural law. Et voila, my method. I observe the facts without biases of the head or heart. I determine the arc’s path, stroll leisurely to its terminus and the truth falls at my feet.

This departure from the traditional brilliance of the classical detective is at times problematic, for there were moments in the film when the audience would no doubt question the legitimacy of Benoit Blanc. Consider the sequence where Marta goes along with Blanc on an investigation in the vicinity of the Thrombey residence. Detective Blanc, distracted by Wanetta Thrombey, the eccentric great grandmother of the Thrombey family, initially blatantly misses a crucial piece of evidence, a cracked wooden frame nearby a window. The frame had been left accidentally by Marta when she was setting up her alibi as instructed by Harlan. It is not until later, when a dog fetches the frame for Blanc, that the detective discovers the piece of evidence.

Benoit Blanc is an unquestionably talented detective [in Knives Out]

Also, consider the scene when Marta asks Blanc to stay in the car, as she has to go on a detour to pick up something. This is an excuse fabricated by Marta so that she could have a secret rendezvous with her anonymous blackmailer. Yet, Blanc does not give the fabrication a second thought and stays in the vehicle as instructed. It is not until later when a siren-wailing ambulance arrives that the detective notices that something is wrong. This seeming incompetence of the detective was even playfully acknowledged towards the end of the film (Johnson, 2019, p.112):

Marta Cabrera: You’re not much of a detective, are you?

Benoit Blanc: Well, to be fair, you make a pretty lousy murderer

The purpose of such peculiar character design may be to create comedic effects and to add a tinge of eccentricity, a quality also inherent within the classical detective as observed in Holmes and Dupin. However, Cawelti’s observation of the trends in the classical detective genre might also offer some explanations regarding the seemingly inconsistent investigative capability of Benoit Blanc. According to the scholar, the overall arch of evolution in the genre has been to give “increasing importance to the intricacy of the puzzle surrounding the crime and less prominence to the detective's initiative in the investigation” (1976, p.84).

Cawelti’s observation noteworthily runs in accordance with Blanc’s explanation of his more passive investigative method (“I determine the arc’s path, stroll leisurely to its terminus and the truth falls at my feet”). Overall, as seen from the character design of Benoit Blanc, Johnson on one hand acknowledges the trope of the brilliant detective, who has the power to lay bare the deepest secrets. Yet, on the other hand, the crafted story follows the line of evolution where the emphasis has been set on the mystery of the crime itself, rather than the absolute celebration of the brilliance of the detective.

Those threatened by the crime but incapable of solving it

Cawelti conceptualised that there are three subspecies for those characters that are entangled in the crime but lack the ability to solve it. Namely, they are “the friends or assistants of the detective who frequently chronicle his exploits; the bungling and inefficient members of the official police …; and, finally, the collection of false suspects, generally sympathetic but weak people who require the detective's intervention to exonerate them” (1976, p.96).

Still shot of the Thrombey family.

The third and final variety, i.e., the collection of false suspects, is particularly interesting in the case of Knives Out. For Cawelti, these characters are in desperate need of the detective, as the latter is capable of restoring their status within the middle-class social order. Further, these false suspects are “usually decent, respectable people who suddenly find themselves in a situation where their ordinarily secure status is no protection against the danger of being charged with a crime and where the police are as likely to arrest the innocent as the guilty” (1976, p.96).

In Knives Out, although in the end it is revealed that these false suspects are not guilty of plotting the murder of their patriarch, they are in no way the decent, respectable people as described by Cawelti (1976). The aforementioned Richard Drysdale was having extramarital affairs unbeknownst to his wife Linda; Walt Thrombey, the youngest son of Harlan Thrombey, overtly threatened to unleash his army of lawyers on Marta if she did not renounce the inheritance; Joni Thrombey, the wife of Harlan’s deceased son Neil, had been committing check fraud using the cheques from Harlan that were supposed to be her daughter Meg’s college tuition fee.

It is also because of these collections of generally despicable false suspects that the ending where not only their social status remains unrestored, but their precious inheritance is still kept from their sweaty grips comes all the more satisfying. In an ironic way, these false suspects turn out to be the perilous force that “threatens the serene domestic circles of bourgeois life with anarchy and chaos” (Cawelti, 1976, p.96) in the first place. As such, the inevitable doom they should face in the end is just as gratifying to feast one’s eyes on as the final apprehension of the true criminal in conventional classical detective stories. This is because it is similarly a reaffirmation of the fated rehabilitation of the established social order.

Knives Out (2019) and the classical detective formula

This article aimed to examine how Knives Out (2019) follows and potentially deviates from the classical detective formula. Overall, the artistry of Knives Out not only lies within its acknowledgment and honouring of genre conventions but attempts at subverting our taken-for-granted understanding of classical detective stories. Unlike most modern detective films, Rian Johnson’s daring attempts at renewing the genre combined with his knowledge of the long-established classical detective formula have worked effectively to create a satisfying viewing experience filled with twists and turns.

References

Cawelti, J.G. (1976). Adventure, mystery, and romance: Formula stories as art and popular culture. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Johnson, R. (2019). Knives out.

Kuokknen, K. (2014). Plot. In P. Hühn, J.C. Meister, J. Pier, & W. Schmid (Eds.), Handbook of narratology. New York, NY: Walter de Gruyter.