Why is character amnesia in China considered problematic?

In this paper, I aim to investigate the extent to which character amnesia is regarded as a problem and why. Furthermore, I will explore measures the government of the People’s Republic of China has taken to handle this issue. My analysis of the policy regarding character amnesia will be based on a framework that combines the policy cycle as mentioned by Howlett, Ramesh and Perl (2009). Eventually, I will offer some recommendations on how to deal with this particular language policy.

Scribble Struggles

Once during my time as a China Studies student at Leiden University, my mother showed me a striking news article regarding language acquisition in China. In fact, this article was not so much about the actual acquisition of language, but rather about ‘forgetting’ certain aspects of a language due to the increased use of technology. More specifically, the article dealt with the case of ‘character amnesia’, or in Chinese 提笔忘字 (tí bǐ wàng zì), which means something like: ‘to pick up the pen but forget how to write the character’. The article argued that character amnesia had become more and more common among people with a character language as their native language, especially in China and Taiwan but also in Japan. Some people, the article claimed, were not even able to write down some of the most simple characters, and had to consult their phones using 'pinyin' (a Romanization system to transcribe Chinese characters) to look them up. At that time, learning how to write Chinese characters had been my daily occupation, so the article frustrated me. I simply could not believe that half of what I was painstakingly trying to comprehend had already been ‘forgotten’ by the Chinese people themselves. If that was a reality, then what was the point of me scribbling notebooks full with these soon-to-be-forgotten characters? I brushed the article aside, thinking it was just some superficial opinion of a person who, for some reason, was not keen on China. After all, I had no choice but to continue my struggle. I still had to graduate.

Character amnesia has become more and more common among people with a character language as their native language, especially in China and Taiwan but also in Japan.

However, when I lived in Peking for a year, my attitude towards this issue changed completely. I experienced for myself how easy it was to send characters messages by text to my friends. After installing the right keyboard settings on my phone, I could just start typing the message in pinyin and the characters would pop up automatically. No need to think about stroke orders, I just had to make sure that I made no mistakes in selecting the right characters for the pinyin I was typing.[1] Even when I did draw a character on the screen, my phone would automatically come up with character suggestions without my even having to finish writing. For typing out essays in Chinese, I simply used a similar pinyin keyboard setting on my laptop. This way of ‘writing’ was just so much more convenient that, if it was not obligatory for me to write some essays by hand, I would probably not have chosen to write characters at all. Then and there, I clearly understood why character amnesia was an emerging issue in countries like China. Even so much so that it had (and still has) the possibility to become a serious problem.

How did we get into this calligraphy conundrum?

PRC Politics

Politics steer policy. To gain insight into the relationship between politics and policy, we turn to the political landscape in China and to the role of the Ministry of Education.

Since 1921, the Communist Party of China (CPC) has been the ruling political party of the People’s Republic of China. The CPC views the world as organized into two opposing camps: socialist and capitalist. They believe that socialism will eventually triumph over capitalism. When the CPC was asked to explain the globalization that China is participating in, it referred to the writings of Karl Marx. Despite admitting that globalization has developed through the capitalist system, the party leaders and theorists argue that globalization is not intrinsically capitalist. The CPC believes that if globalization were purely capitalist, it would exclude an alternative socialist form of modernity. Globalization, as it happens with the market economy, is therefore argued not to have a specific class character. This way, the CPC is able to pursue socialist modernization by incorporating elements of capitalism (Heazle & Knight, 2007).

In 2000, the 'Three Represents' have been ratified by the CPC as a guiding socio-political theory. They refer to what the Party currently stands for. These 'represents', or political stances, entail ‘representation of advanced social productive forces’, ‘a progressive course of China’s advanced culture’, and 'fundamental interests of the majority’. According to CPC theory:

"In present-day China, developing advanced culture means developing a national, scientific, and popular culture that is geared to the needs of modernization, the world and the future. (…) At the same time, the development of advanced productive forces is inseparable form cultural issues, such as ideology, ethics, education and science, because the general ideological and cultural levels of a given society directly affect the quality of the work force." (Three Represents, 2006)

The MoE (Ministry of Education) of the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949. Since the end of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) the educational system in China has been focused on economic modernization. Modernizing education was critical to modernizing China, and the education policy was mainly aimed to narrow the gap between China and other developing countries. The responsibilities of the Ministry of Education include the following:

" To formulate guidelines and policies for the nationwide standardisation and promotion of the spoken and written Chinese language; to compile medium and long-term plans for the development of the Chinese language; to formulate standards and criteria for Chinese and languages of ethnic minority groups and to organize and coordinate the supervision and the examination of the implementation of the standards and criteria; to direct the popularization of Putonghua and the training of teachers of Putonghua." (The responsibilities of the Ministry, n.d.)

Additionally, the Law on the Standard Spoken and Written Chinese Language of the People’s Republic of China states:

"Article 1 - This Law is enacted in accordance with the Constitution for the purpose of promoting the normalization and standardization of the standard spoken and written Chinese language and its sound development, making it play a better role in public activities, and promoting economic and cultural exchange among all the Chinese ethnic groups and regions.

Article 2 - For purposes of this Law, the standard spoken and written Chinese language means Putonghua (a common speech with pronunciation based on the Beijing dialect) and the standardized Chinese characters.

Article 3 - The State popularises Putonghua and the standardized Chinese characters.

Article 4 - All citizens shall have the right to learn and use the standard spoken and written Chinese language. The State provides citizens with the conditions for learning and using the standard spoken and written Chinese language. Local people’s governments at various levels and the relevant departments under them shall take measures to popularise Putonghua and the standardized Chinese characters.

Article 5 - The standard spoken and written Chinese language shall be used in such a way as to be conducive to the upholding of state sovereignty and national dignity, to unification of the country and unity among all ethnic groups, and to socialist material progress and ethical progress." (Law on the Standard, 2009)

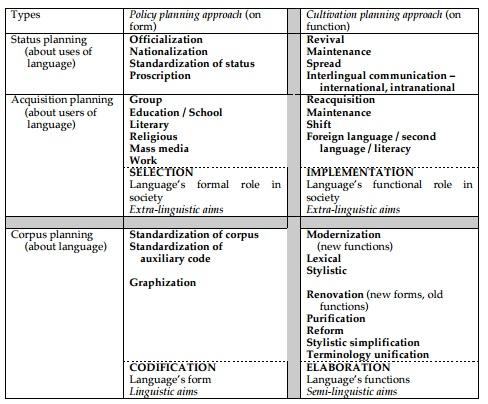

When approaching language policy and planning, scholars distinguish three different forms: status planning, corpus planning and acquisition planning (Cooper, 1989). According to Hornberger (2006), status planning refers to efforts directed toward the allocation of functions of languages/literacies in a given speech community; corpus planning focuses on the adequacy of the form of languages/literacies; and acquisition planning is directed towards creating opportunities and incentives for learners to acquire additional languages/literacies. From the first three situations listed above, we see that the Chinese government pursues goals from all three dimensions: selecting a national language, reforming its writing system (simplification, standardization and Romanization), and promoting it in the educational system (Wan, 2014). We can also conclude here that the tibiwangzi-phenomenon is inseparably linked with the urge for modernization and globalization of the PRC.

Societal context and historic development

All policies start with a problem: a discrepancy between the norm and an impression of an actual (or future) situation. To understand the ‘norm’ and the ‘impression of the actual or future situation’ in this case, we first need to dive into the societal context of the problem: the globalizing world. In a globalizing world, it is important to consider language as a complex system of mobile resources, shaped and developed both because of mobility and for mobility. This assumption is a paradigmatic shift away from a linguistic and sociolinguistic tradition in which language was analysed primarily as a local and stable system of signs, attached to an equally local and stable community of speakers (Kroon et al., 2011). In his article Super-diversity and its implications, Steven Vertovec (2007) made clear that the general view on diversity in today’s society was outdated and needed to be adapted. He wrote the article as a wakeup-call to social scientists and policy makers suggesting that they take the conjunction of ethnicity into more account when considering the nature, interaction, composition and public service needs of various ‘communities’. He pointed out that over the past two and a half decades, society has changed dramatically.

An important characteristic of superdiversity is the development of new communication technologies that affect the lives of virtually everyone. The ‘one nation, one language, one people’ notion has been gradually replaced by a more differentiating vocabulary which includes ‘communities of practice’, 'institutions’ and ‘networks’ as the mobile and flexible sites in which groups emerge and circulate (Blommaert & Rampton, 2011). Thus, this paradigm shift allows us to reconsider many of the assumptions of linguistics and sociolinguistics, emphasizing permanent instability and dynamics. The shift also promotes construction of radically different notions of order in the linguistic and sociolinguistic system. The order we now observe is no longer an order inscribed in stable structural features of language, but an order embedded in the trajectories of change and development within the system. The effects of globalization have shaped highly-complex, super-diverse sociolinguistic environments, populated by people with wildly different backgrounds and life paths. Furthermore, these people possess different forms and degrees of access to sociolinguistic and semiotic resources and have their own frames for interpretation. (Kroon et al., 2011). In the case at hand, there has undoubtedly been a digital revolution which has completely changed the way Chinese is written (Kaiman, 2016).

As for the Chinese written language, there has been a digital revolution which has completely changed the way we write Chinese.

Chinese characters (hànzì) provide a writing system for Chinese languages and languages in neighbouring countries like Japan and Korea. Chinese characters have existed for over three thousand years and have been used in eastern and south-eastern Asian areas for ages (Hsu et al, 2012). In the earliest Chinese writing, pictographic origins are quite obvious. Over the course of time, however, the script underwent many changes; by the time of the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), the script had lost most of its pictorial quality. The present day standard script took shape during the third and fourth centuries CE. After that, the form of the script remained surprisingly unchanged until modern times. In the 1920’s and 1930’s, many Chinese intellectuals viewed the script as a serious problem in China's attempt to become a part of the modern world. It was portrayed as cumbersome, difficult to learn and out of date. As a result, many advocated the outright abandonment of the traditional script in favor of an alphabetic system (Norman, n.d.).

However, within Chinese tradition, the Chinese script is about more than merely producing texts alone. It is said to represent the self of the writer, aesthetic principles, and the relationship between his or her inner world in regards to nature and society. These cherished attitudes, developed more than 2000 years ago, are still seen as some of the core values of Chinese culture. The age old pedagogy of rewriting and assimilating through repetition is sustained; it is believed that the cultural values are not passed on just by the rational process of assimilating thoughts and ideas, but also learned through bodily actions. The endured structure and the cultural and moral values implied in Chinese characters are passed on through the practice of writing itself and in understanding the related rules of scribing. In present day, such cultural meanings are still significant and influential. This explains why writing has been subject to intense debate in the context of modernization. (Hsu et al, 2012).

Another problem that the proponents of alphabetic writing were not able to overcome was that for such a writing system to be practical, it would have to be adapted to various regional dialects. Such a move was viewed as potentially divisive and harmful to the idea of a single Chinese nation. In a country with hundreds of different dialects, a common script that is independent of this dialectal diversity is a powerful symbol of national unity (Norman, n.d.). When the country was united under the Qin Dynasty (221 – 206 BC), the Chinese written language was standardized, further solidifying the largest nation-state in the world. The Chinese language landscape is immensely diverse and regional; even local dialects could be unintelligible to Chinese-speaking outsiders. Without unified written language, communication between different regions in China would be immensely difficult (Paredes, 2014; McDougall & Louie, 1997).

Ultimately, all ideas for Romanization of the Chinese script were abandoned. Attention turned to simplification of the traditional script with the idea being that the writing system would be easier to learn. It was not until the 1950’s that effective steps were taken to carry out such a plan. In 1956 and again in 1964, lists of simplified characters were officially adopted in the People’s Republic of China. The creation of the ‘common language’ (putonghua/guoyu, mandarin) was used as a means of expression for all people in all parts of the country. Like the vernacular, it could also be written down using the old ideographic script, but simplified, making it easier for people to become literate. Hong Kong and Taiwan continued to use the traditional characters, a situation that still prevails. Finally, in 1957 an alphabetic system called ‘pinyin’ was introduced in the People’s Republic of China as an auxiliary system to be used in teaching correct pronunciation in schools and for use in various sorts of reference works (Norman, n.d.).

Classic pedagogy of Chinese literacy emphasizes the ability of recognition of characters as well as the ability of writing. As stated, there is a deeply entrenched belief that the only way to learn how to write Chinese characters is through regular and repetitious writing over a lengthy period of time (Hsu, 2012). One can’t improve his or her writing skills by reading and speaking alone. Because of their complexity and multiplicity, writing Chinese characters correctly is a highly neuromuscular task. They simply must be practiced hundreds and hundreds of times to be mastered. And, as with playing a musical instrument, one must practice writing them regularly or the control over them will simply evaporate (Mair, 2010). Hence, native Chinese-speaking children are supposed to write as many characters as possible during the entire course of their school age, which is a very time consuming task (Hsu et al, 2012).

Estimates of average native-speaker character knowledge vary considerably. Some people estimate a common average to be 3000-4000 characters, and others believe educated people know about 8000 characters. For the average adult, the ability to handwrite 3000 characters on demand would be considered sufficient. Academic and professional or technical literacy can require many more characters. Part of the variability in count involves differences in level of education, and also the issue of active- versus passive-character knowledge. Active-character knowledge implies the person can readily write the character and that the vocabulary is used in correct context. Passive knowledge of characters entails being able to recognize a given character when it’s presented to the reader, but if called upon to write the character at random, the writer would have to ask for help or consult a reference (Williams, 2016).

Modern globalization as an added problem

Although the classic ideologies and learning processes that are associated with Chinese characters remain important, it has been subject to change within the context of globalization. In recent years, the pedagogy has been accommodated to the needs of the learners, especially in the case of foreign learners. With the popularity of the internet, computer-assisted language instruction has become increasingly popular. Moreover, through the process of Romanising Chinese characters, as well as the increased use of personal computers and mobile devices, handwriting is gradually replaced by typing and phonetic entry (Hsu, 2012; Kaiman, 2016). In 2009 Victor H. Mair, professor in Chinese Language in Literature at the University of Pennsylvania, surveyed nearly two hundred Chinese-literate individuals. About half of them were professional teachers of Chinese, and they hailed from around the world. In the study, he asked them what their preferred IME (Input Method Editor) was. Around 98% of the respondents used pinyin to input Chinese characters, with a remaining handful using a shape based system or a stylus to write characters on a tablet (Mair, 2010).

Another feature that has gained huge popularity in China recently is that of ‘sending voice messages’ (发语音, fā yǔyīn). Chinese Whatsapp equivalent 'WeChat' was the first in the world to introduce this feature in its app. Social media research by University College London has shown that Chinese WeChat users find voice messaging convenient because it eliminates the need to text. Informants have reported that sending written messages always takes more time, and that inputting Chinese characters was a struggle (Wang & McDonald, 2013). With voice messaging, or even with pinyin input, people do not need to memorize the exact order of each stroke of a character when typing a text. They can just rely on knowing the pronunciation and recognizing the character. The prevalence of typing and texting on cellular devices has been correlated to reduced active-character knowledge by Chinese natives, leading to the tibiwangzi-phenomenon (Williams, 2016).

With voice messaging, or even with pinyin input, people do not need to memorize the exact order of each stroke of a character when typing a text. They can just rely on knowing the pronunciation and recognizing the character.

Furthermore, over the last decade English has become a prominent language in the People’s Republic of China. Driven by China’s rise to global prominence in economic and political affairs, China has begun to develop itself as a globalized country. International events such as the Olympics (Beijing 2008) and the World Exhibition (Shanghai 2010) accentuate this ambition. Moreover, a strong drive towards a general provision of English among the middle-class population articulates a process of global awareness of the contemporary Chinese citizens (Kroon et al., 2011). The increased access to the English language also gave rise to certain changes within the Chinese language itself. When I took Mandarin language courses at Peking University, I learned that the Chinese word for ‘email’ was ‘diànzǐ yóujiàn’ (电子邮件), but I almost never had to use it. Instead of saying: “Fā gěi wǒ diànzǐ yóujiàn” (send me an email, 发给我电子邮件), I quickly learned that simply saying “Fā gěi wǒ email” (发给我email) was much more common. Like this, Chinese internet users often rewrite a standard Chinese phrase by peppering it with numbers, symbols and phonetic translations from English. Sometimes using words that sound the same but are written differently to mask what they mean, often to elude China’s internet censors. Chinese web-speak is referred to as huoxingwen (火星文, huǒxīng wén) or the ‘language from Mars’ (New calligraphy classes, 2011).

Up to now, the Chinese government did not make any official statements directly regarding the tibiwangzi-phenomenon. However, since 2011, the Chinese government (more specifically the MoE of the People’s Republic of China) has undergone several educational reforms that have been associated with this kind of language development (Mair, 2012; Zhu, 2013; Paredes, 2014; Wu & Liao, 2012). Evidently, although the Chinese government supports technological development and a more general proficiency in English among the Chinese middle-class, the declining knowledge of the Chinese script among Chinese citizens is considered problematic by Chinese officials. Not only does this phenomenon challenge the intended high-status of Chinese culture as a whole, but also it is considered dangerous to the notion of unity among the local and regional cultures in China; therefore, it is in contradiction with the national law.

Policy

Known measures taken by the MoE include: increasing calligraphy classes for elementary and high school students, training teachers in calligraphy, teaching Chinese writing to foreign students, and making changes to the scoring-system of the Chinese college entrance examination (gaokao). Besides this, some initiatives have been set up by other educational authorities and ‘worried’ parents, such as teaching elementary students how to read the Classics.

Calligraphy is one of China’s major visual arts; many painters and scholars were (are) also accomplished calligraphers. The cultivation of artistic writing is only one of many practices that show how deeply the writing system is rooted in Chinese culture. Despite recurrent suggestions to replace the traditional script with alphabetic writing because of all its obvious conveniences, the Chinese writing system remains integral to Chinese self-definition (Norman, n.d.). According to a notice issued by the MoE on its website on August 26th 2011, senior elementary school students were supposed to have one hour of calligraphy class every week, and high schools were to offer calligraphy as an optional course. According to the Education Ministry, calligraphy courses would teach students to write standard Chinese characters in a proper way, using the right gestures. It was advocated that students in higher grades learn to appreciate the work of ancient calligraphers. The ministry also urged schools to train teachers and establish specific plans for calligraphy instruction, as well as host various calligraphy-related activities after school such as inviting calligraphy experts to give lectures (Internet users vote, 2011).

After this announcement, the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission had instructed that marks for calligraphy will be listed separately from the study of Chinese in students' report cards and will account for 5 percent of their overall academic score. With no precedents to follow, 55 schools in the city began to conduct calligraphy classes in a pilot program, but soon encountered difficulties. City media reported that many schools lacked qualified or competent teachers and several principals had to ask their art teachers to run the classes even if they didn't know a lot about the subject (Wang, 2012). The 2011 guideline was not well implemented due to the lack of specialized teachers and proper teaching materials; furthermore, students took preference to other courses that were evaluated by academic scores. The MoE responded to this by stating it would cooperate with relevant mass organizations to promote and standardize calligraphy education (China to strengthen, 2013). One of these mass organizations is the China Calligraphers Association[2]. The China Calligraphers Association works to train more teachers in the art of calligraphy to improve professional standards. It has set up calligraphy centres to train and test teachers from local schools in each capital of the country's provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities (Zhu, 2013; Wang, 2012). Moreover, In 2013, the Beijing Educational Examinations Board announced major changes for the upcoming 2016 Beijing gaokao, the infamous Chinese college entrance exam. The Board decreased the point value of the English section of the 2016 Beijing gaokao from 150 to 100 points. The Chinese section, which includes a handwritten essay, increased from 150 to 180 points, shifting the emphasis from English back to written-Chinese (Paredes, 2014).

Additionally, educational authorities in central China's city of Wuhan required their elementary school students to read classical texts for 20 minutes in morning and practice writing Chinese characters for as much duration in the afternoon every day. This so-called 'Get Close to the Mother Tongue' campaign was supported by many ‘worried’ parents of the students. The campaign began in the city's Wuchang district in 2010 and caught the eye of the MoE in 2012. Hereafter, the ministry made plans to roll out similar campaigns elsewhere in the country (“Literacy drive”, 2012). A report by the ministry stated that campaigns like this will increase young students’ knowledge of traditional culture, make them more patriotic and help them recognize the dignity of their native language (Wu & Liao, 2012).

Finally, since China has opened its doors to the world, another new and rather unexpected way to preserve the tradition of writing Chinese characters appears to be emerging: teaching the language to foreigners. Just like it was for me, most of the foreigners that study Chinese in China begin by learning how to write characters, and when they return back home, it is hoped that they will take this tradition with them encouraging others to do the same (Paredes, 2014). Even at Leiden University, learning how to write a significant amount of both traditional and simplified characters was one of the most, if not the most, important skills that had to be acquired in order to complete the study successfully. After all, the university hosts one of the many Confucius Institutes: educational non-profit organizations that promote the Chinese language and culture overseas, which are affiliated with the MoE of the People’s Republic of China.

Analysis

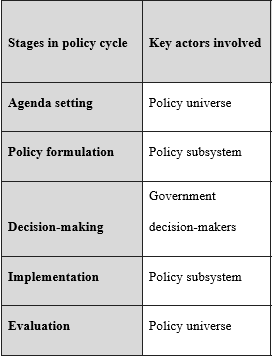

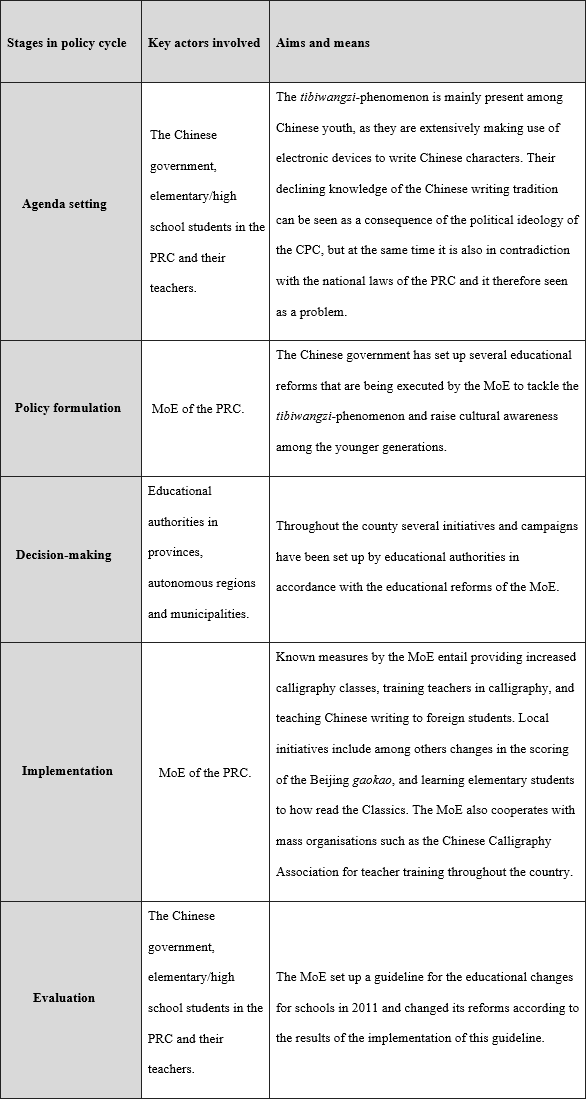

The policy cycle often is a starting point for practitioners to develop and analyse policies. It incorporates fixed features that can be found in any form of policy-making. As different versions of this cycle exist, in this paper I will use the policy cycle as explained by Howlett, Ramesh and Perl (2009). They opt for a clear-cut analytical framework that can easily be applied in a consistent way. The policy cycle, as explained by these researchers, includes five successive phases that take place within any policy making process. These phases are: agenda setting, policy formulation, decision-making, implementation, and evaluation. Besides this, Howlett, Ramesh and Perl (2009) also distinguish specific actors that are participating in each phase of this cycle, namely: the policy universe, the policy subsystem, and government decision-makers. The policy universe can be thought of as an all-encompassing composition of the possible international, state, and social actors and institutions that directly or indirectly affect a specific policy area. Each sector or issue area can be thought of as a subset of that universe, as a policy subsystem in which individual government decision-makers act (Howlett et al., 2015). For analysing the language policy for the issue of the tibiwangzi-phenomenon, I have constructed a similar table as shown in figure 1. For each phase in the policy cycle, I have provided key actors involved and the aims and means that may come into play. Here, an aim is a system of thought or situation that the actor thinks to be desirable and that can be promoted by actions performed by this actor. An action (or complex of actions) that an actor wants to carry out/use, or that an actor can carry out/use, to achieve its aim is called a means.

Figure 1: Analytical framework for establishing policy actors (based on Howlett et al., 2015: 13)

Besides this, the process of language planning that has been carried out with regard to the tibiwangzi-phenomenon can be examined in terms of corpus, status and acquisition planning using Hornberger’s (2006) integrative framework as a tool of analysis for language policy and planning goals (figure 2).

Figure 2: integrative framework as a tool of analysis for language policy and planning goals (Hornberger 2006, p. 29)

The analysis combining the frameworks given in figure 1 and figure 2 is presented in figure 3. It intends to give a simple overview of the structure of the policy case highlighted in this article.

Figure 3: policy cycle analysis of the tibiwangzi-phenomenon

We have seen that the modernization of the Chinese language was a direct consequence of earlier language policies based on corpus planning, status planning and acquisition planning. Now, considering the tibiwangzi-phenomenon, we can see that new measures are being taken that especially build on acquisition planning: the reacquisition of calligraphy skills in school, maintenance of the knowledge of writing characters among students, etc. Status planning measures are also being taken: revival of the writing tradition, standardization of the status of the Chinese language, etc..

Conclusion

Looking at the analysis of the tibiwangzi-phenomenon, it seems that the language policy regarding this problem is a balancing act. The aim for (technological) modernization in the PRC has made its citizens, especially the younger generation, very tech–savvy and globally-orientated. The overabundance of electronic devices and the extensive use of pinyin input methods and voice recording texts instead of handwriting characters, is only a logical consequence of the modern developments of the country. It is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, the Chinese government stimulates digital innovation and an open-door policy, but on the other hand, it is still reluctant to some of their implications.

The overabundance of electronic devices and the extensive use of pinyin input methods and voice recording texts instead of handwriting characters, is only a logical consequence of the modern developments of the country.

If this is the case, there is not a golden rule that will be able to solve this problem to the utmost extent. It is evident why the Chinese government started to stimulate cultural awareness among students, but I agree with Victor Mair (see Appendix 5.C) on the fact that their means might not have a long term effect. Digital innovation is a development that undoubtedly will continue to thrive, and handwriting will be less and less practiced... not just in China, but all over the world. However, the Chinese culture does have a very particular and persistent writing tradition, and this will definitely not disappear overnight. Yet, it also will continue to be a subject of change. Eventually, the Chinese government will have to evaluate which facets of this tradition are suitable to withstand the test of time and go on to encourage them. Writing-traditions that are not ‘future-proof’ will encounter resistance with the people when these are still imposed on them.

Endnotes

[1] Some characters share the same pinyin transcription, for example ‘ma’ (马, horse) and ‘ma’ (妈, mother).

[2] Established in 1981 by Chinese authorities.

References

Blommaert, J. & Rampton, B. (2011). Language and Superdiversity. Language and Superdiversities, 13(2), pp. 1-21.

China to strengthen calligraphy education (2013, August 26). Retrieved from: http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/806322.shtml.

Cooper, R. L. (1989). Language planning and social change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Heazle, M. & Knight, N. (2007). China-Japan relations in the Twenty-first century: creating a future past? Chettenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Hornberger, N. (2006). Frameworks and models in language policy and planning. In T. Ricento (Ed.), An introduction to language policy: Theory and method (pp. 24-41). Malden, MA: Wiley.

Howlett, M. & Perl, A. & Ramesh M. (2009). Studying Public Policy: Policy Cycles & Policy Subsystems. New York: Oxford University Press.

Howlett, M. & Mukherjee, I. & Koppenjan, J. (2015). Policy learning and policy networks in theory and practice: the case of Indonesian biodiesel policy network. Paper to be presented at the PL&PC panel of the ICPP conference, Milan.

Hsu, H. & Pang, C. L. & Haagdorens, W. (2012). Writing as cultural practice: case study of a Chinese heritage school in Belgium. Procedia, 47, pp. 1592-1596.

Kaiman, J. (2016). Learning Mandarin is really, really hard – even for many Chinese people.

Kroon, S. & Jie, D. & Blommaert, J. (2011). Truly moving texts. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, 3. .

Internet users vote for compulsory calligraphy classes. (2011, August 28).

Law on the Standard Spoken and Written Chinese Language of the People’s Republic of China. (2009, July 21).

Literacy drive for gadget-crazy Chinese kids. (2012, December 4).

McDougall, B. S. & Louie, K. (1997). The literature of China in the twentieth century. London: C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd.

Mair, V. (2010). Character amnesia. .

Mair, V. (2012). Character amnesia revisited.

New calligraphy classes for China’s internet generation. (2011, August 27).

Norman, J. (n.d). Chinese writing: traditions and transformations.

Paredes, M. (2014). A question of character. .

The responsibilities of the ministry of education. (n.d.).

Three Represents. (2006, June 23).

Vertovec, S. (2007). Super-diversity and its implications. Ethinc and Racial Studies, 30(6), pp. 1024-1054.

Wan, D. (2014). The history of language planning and reform in China: a critical perspective. Working papers in educational linguistics, 29(2), pp. 65-79.

Wang, X. & McDonald, T. (2013). Time to face your own voice: voice messaging on Chinese social media.

Wang, Y. (2012). Writing for the future.

Williams, C. (2016). Teaching English Reading in the Chinese-Speaking World : Building Strategies Across Scripts. Singapore: Springer Verlag.

Wu, Z. & Liao, J. (2012). Writing wrongs of ‘character amnesia’.

Zhu, J. (2013). Chinese characters under threat in digital age. R