The mockumentary film and TV show ‘What We Do In The Shadows’

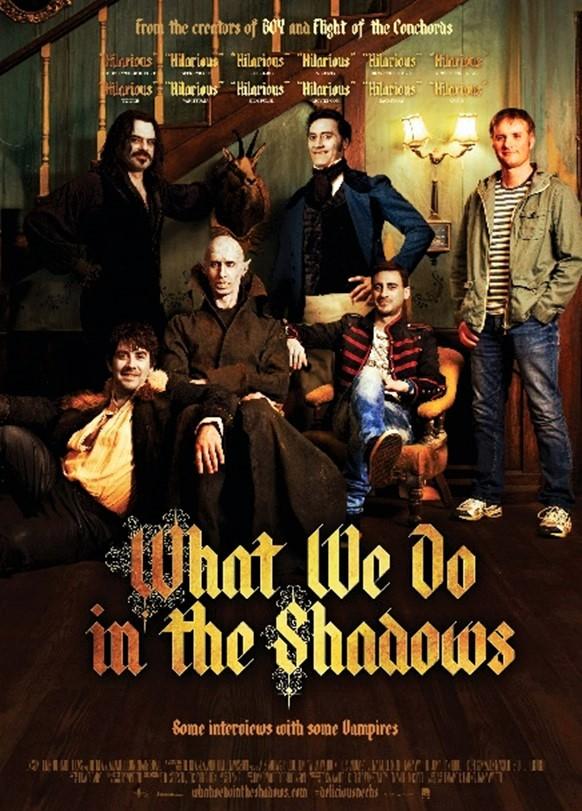

You are wrong when you thought that modern cinema and popular culture were done with vampirism. Co-written, directed, produced and starred by Oscar-winner Taika Waititi and Jemaine Clement, both from New Zealand, created What We Do In The Shadows, a mockumentary film (2014) about centuries-old vampires living together as a dysfunctional family among 21st-century humans.

It mixes comedy, fantasy and horror genres and cleverly blurs the boundaries between the fictional world and character-building and representations of everyday life. It has an audience score of 87% on Rotten Tomatoes, has been nominated and has won national film (festival) awards.

Figure 1. Official film poster

In 2019, a spinoff TV show aired, set in the same universe. Instead of Wellington, New Zealand, another set of vampires live on Long Island, New York, among ordinary Americans. The film's characters sometimes make a guest appearance on the show as members of the vampirical council. Waititi had other projects, so Clement and other writers created the show for the most part. The series counts three seasons, with a fourth on its way and two more confirmed due to high demand and positive reviews. The show also takes on the mockumentary style and contains functions of intertextuality. Even more so than the film, it has the room to explore aspects of mundane everyday life and reflect on other (famous) works about vampires and dealing with technology.

In this essay, I will answer the central question: How do the movie and TV shows play with the mockumentary genre and its hybrid fact-fictional format and content? Firstly, I will conceptualise the mockumentary and look at the genre's functions to reflect on the film and show's incorporation of the genre. After that, I will discuss the film and show's playful representation of vampires and the blurring of boundaries of reality and fiction, using and defining concepts such as postmodernism and representation. I will also discuss elements of intertextuality incorporated in both works. Finally, everything that has been discussed will be considered to argue what gives the work its charm.

Theory on mockumentaries and the incorporation of the genre in the film and spinoff series

From the early 2000s, hybrid fact-fictional forms were no longer on the margins but at the centre of media production (Lipkin et al., 2006). The mockumentary is a genre that the writers of What We Do In The Shadows reinterpreted to make a hybrid fact-fictional film. The mockumentary can be defined by its intertextual and subversive functions. Mock documentaries are entirely fictional and subversion of factuality through parody, critique and deconstruction. Simultaneously, they appropriate the aesthetics of documentaries closely to emphasise the humour and for style-related reasons (Lipkin et al., 2006). The mock-documentary questions the form and content of television documentary formats and the direct relationship between image and referent (Lipkin et al., 2006). Another typical genre characteristic is the close relationship between the producer and the audience (Lipkin et al., 2006).

The audience is made aware throughout the work that it is a parody of the documentary form.

The audience is placed in a privileged position of knowing (Campbell, 2017). Audiences must be in on the joke to be able to access and participate first in the humour, then in the cultural and political critique on offer (Lipkin et al., 2006). The mockumentary's film techniques offer a sense of unpolished authenticity, such as shaky handheld camerawork, refocussing and zooming in and out of the action, frequent camera interviews called talking heads, and montages of historical drawings, paintings, and photographs of the characters throughout their histories (Fhlainn, 2019), as well as voiceover commentary and captions. Such documentary codes are subverted in the mock-documentary: they appear factual but have been convincingly faked.

The film incorporates documentary elements, especially in the camerawork and the vampires' interactions with the camera. Vampire Viago (379 years old), played by Taika Waititi, is first introduced and takes the audience around the house to introduce his roommates. The vampires are aware of the cameras following them for a documentary and frequently break the fourth wall when something happens. There are also multiple occasions when the camera crew must run for their life or get hurt when other vampires or werewolves attack them. It almost feels like a live reportage rather than a documentary.

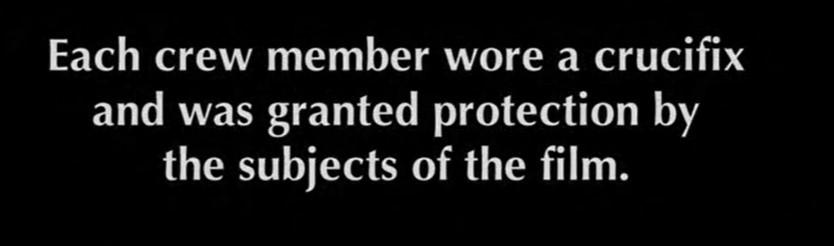

Figure 2. A caption/disclaimer shown at the start of the film

The picture above shows a caption before the film began, a documentary code functioning as a disclaimer for viewers that the vampires would not eat the crew because the crew had crucifix necklaces on at all times and the vampires promised 'protection'. Audiences are in a position of knowing and are thus in on the joke that this is not factual information about the filming conditions. The TV show is a more big-budget production. Still, it keeps the aesthetics of the documentary genre, especially the talking heads, fourth wall break and documentary codes like voiceover by the characters and the display of artefacts showing the vampire's history. Moreover, it gets acknowledged by the vampires that having cameras around and doing interviews is part of their everyday life. For example, one of the show's vampire characters, Nandor, reacts when he gets interrupted by his human 'familiar' and helper, Guillermo: "Can't you see I'm doing my talking to the camera thing?"

The video shows the intro of the show's pilot. The opening intro appears before each episode and offers an introduction to the characters. Documentary codes like oil paintings and old pictures of their past life and life together as a group are shown. Every episode has a cold open, a typical narrative style for sitcoms. For the pilot, the familiar Guillermo wakes his master vampire Nandor the Relentless, who makes a grand entrance out of his coffin as if showing off to the camera. Opening the episode like this is a narrative technique that immerses viewers in the story's action from the first shot (Masterclass staff, 2022). The film's intro also uses the catchy theme song 'dead'.

In making both of these fictional works, there was quite some room left for improvisation for the actors. Shooting the film, Waititi disclosed that they did not let the actors read the total script and had to act toward something. That's also why the editing took a long time because they had way too much footage (BAFTA Guru, 2019). The show is shot using a big-production set with attention to detail to make the vampire's house realistic and a playground for the actors to freely walk in and let the cameras follow them. Documentary codes like paintings and pictures are spontaneously shown on camera. This improvisational aspect triggers the level of belief in the events unfolding and intensifies the audience's experience of watching it as a documentary (Lipkin et al., 2006). Arguably, the improvisation and freedom on set also enriched the characters and made them funnier.

Finally, another mockumentary characteristic is the questioning of form in terms of permissibility, usefulness and risk of mixing the functions of documentary and comedy (Lipkin et al., 2006). It combines the documentary format with multiple kinds of comedy (Masterclass staff, 2022):

- Situational comedy: a typical form used in sitcoms, drawing humour from relationships and dynamics between a recurring cast of characters in a consistent setting.

- Dark comedy: dark humour to discuss morbid topics like death.

- Deadpan comedy: using dry humour through an intentional lack of emotion while talking about absurd topics.

- Self-deprecating humour: characters joking about their shortcomings and masking their insecurities.

- Wordplay. For example, when vampire Nandor calls crepe paper 'creepy paper' unironically.

- Parody, imitating existing works and characters through exaggeration. The medium does not force itself to be too spectacular in the special effects. Especially in the film, there is no big-budget CGI, which also protects its documentary form and keeps the focus more on the comedy aspects. When CGI was used, it was with a comedic intention to exaggerate.

The postmodern representation of vampires unleashed in mundane 21st century New Zealand & America

What We Do In The Shadows provides candid insights into vampirism in the contemporary domestic space. Their world relates to our world, but the characters are invented. The movie version's central themes and ideas are expanded and further developed in the TV show. The fictional works offer a visual portrayal and imagination, called Vorstellung, of a what-if context. It is an entirely invented narrative (Cohn, 2000). However, there is always some truth to fiction. The central function of the vampire in both pieces is to give an immortal perspective to reflect on reality and everyday human experiences, struggles and emotions and, ultimately, find the comedy in it. Every character has their desires, talents, emotions and realisations as humans do. It drives the characters and makes them comic in their way.

No experience is too crazy for the vampires, especially in the show: they get drunk or high, get depressed or have an existential crisis, become addicted to gambling, fall in love, you name it. Like in The Office, the film and show's characters are dysfunctional families. They are stuck in a house together but love each other in their own way. For instance, the movie starts with Viago calling a house meeting in the kitchen because no one is doing the dishes and fighting each other when no one wants to do it. The vampires are written using irony as human idiot identities. Irony can be seen as a postmodern and typical comedy style in the mockumentary. What We Do In The Shadows offers a satirical representation of vampires dealing with human things and the mundane 21st-century human. The vampires have their official rules (do not kill your own kind!) and governing body, like headquarters, events and legal system: the vampiric council. They also have werewolves as their common enemy, like cats (vampires) and dogs (werewolves). This tension is satirically represented in both the film and TV show.

The show's characters are built according to the American imagination of coming to the New World from different areas of the world to settle domestically. They try to rule the powerful land as they see it as a suitable place to advance their evolution, which goes wrong. Central themes are the unease in which they experience immortality and assimilation to the digital age, social media, and the mundane American (Fhlainn, 2019). The works satirically and sometimes critically comment on aspects of modern America from a Western perspective. Multiple times, the show's vampires collide with America's bureaucracy, like when they go to conquer America and find themselves very out of place at the New York council meeting. In another episode, vampire Nandor intends to become an American citizen. He has to endure a long process of filling in forms and being interviewed by a government worker. A line by Nandor functioning as social commentary: "Government workers are immune to hypnotism; it's like their souls are dead or something." Again, the audience must be all-knowing to be in on the joke.

The vampires are presented according to iconic signs they have been given in literature and film adaptations over the years. They are also still evolving as iconic mythical creatures related to postmodernism. As Fhlainn (2019) discussed, vampires are excellent receptors to change; they are constantly in a state of flux or evolution. The period of Postmodernity, characterised by eroding certainty and voicing scepticism, has offered spectacular potential for the future of the vampire. The vampires are written as fluid and transformative subjects with vampirical traits but human-like identities (Fhlainn, 2019).

In both works, the portrayal of vampires is played and experimented with, searching for a unique presentation of vampires. Original characteristics are given to the vampires and typical features that are modern aesthetics, recognisable and consistent (Lyotard & Bennington, 2010). Such physical features are fangs, pale faces, red eyes, and gothic clothing. Also, mannerisms like being 'allergic' to silver and Christianity, sleeping in a coffin, the ability to fly and hypnotise, no reflection, burning when exposed to sunlight and favouring virgins as their victims are recognisable. There is also the hierarchy: the older the vampire, the more respected and feared.

Figure 3. Left: Viago, Nick & Vladislav (film), Middle: Petyr (oldest vampire film), Right: Lazlo, Nadja & Nandor (show)

The characters, especially from the film (left and middle picture), are recognisable because they are based on historical or literary figures; another characteristic of the mockumentary is that it takes cultural, social and political icons as their object of parody (Lipkin et al., 2006). Fiction always has a paratext, referencing other works and thus is deeply indexical. Each character has a cinematic parallel and is thus intertextual (see pictures above). Vladislav, played by Clement, is inspired by Vlad the Impaler, the cruel Romanian ruler who himself was Bram Stoker's inspiration for Dracula. Viago, in his classically elegant clothes and personality inspired by Pride and Prejudice's Mr Darcy, conjures Louis de Pointe du Lac, played by Brad Pitt in 1994's Interview With a Vampire. With his more modern outfits, Nick hints at Twilight's Edward Cullen (Lewis, 2019).

The film and show's indexicality & originality

Besides representing other vampires, the vampires also consciously reflect on the popular culture of cinematic vampires to playfully portray their traits and allure to mock their twentieth-century dominance (Fhlainn, 2019). The show is full of references and cameos of actors who have played vampire characters in other works. Multiple references are made towards Twilight, the famous franchise, by satirically commenting on Edward Cullen being glittery in the sun. They also recreate the famous baseball scene using the same song, but they give a twist to it.

Figure 4. Members of the vampirical council including Viago and other vampire characters from cinematic adaptions

Furthermore, in the trial episode (S1xE07), everyone on the vampiric council portrays an iconic vampire character from vampire films and chronicles, coming together like a vampire reunion (see link and picture). They reference the actors who portrayed such vampire characters, for instance, that 'Rob' (Robert Patterson) could not be there.

It is worth mentioning that the works do not only build their characters using and referring to existing characters. The show makes room for originality, enabling reinterpretations and the exploration of diverse characters, traits and the vampires' histories: Lazlo is a British aristocrat, Nadja is Eastern-European with a typical accent, and Nandor The Relentless used to be a fierce ruler of a small defunct empire, now Iran. Nandor's familiar Guillermo de la Cruz finds out he has the DNA of a famous Dutch vampire hunter, Van Helsing, a fictional character adapted in TV and cinema, being the arch-enemy of Count Dracula (again: intertextuality). Yet, Guillermo still desires to become a vampire and be loyal to serve one, one of many incorporations of irony. He often breaks the fourth wall when one of the vampires says or does something dumb.

A new kind of vampire, a modern monster, is introduced: the energy vampire

Other legendary mythical creatures, like werewolves, ghosts, witches and zombies, are also included in the mockumentary as characters, more so than in the film. The characters are also up-to-date with popular culture. Viago did not want to miss RuPaul's Drag Race. Elvis Presley, who is not dead but turned into a vampire by Lazlo, turns out to live in their basement making music. As mentioned before, the show creates a bond between the producers and the audience. The characters speak to a knowing audience, who are in on the jokes.

Figure 5. The energy vampire Colin Robinson

In the show, a new kind of vampire has also been introduced: the energy vampire, Colin Robinson (see picture). The character is meant to be the modern monster. The character is an original vampire with relatable, stereotypical human characteristics. Everyone comes across an energy vampire in their life. Healthline states: 'They feed on your willingness to listen and care for them, leaving you exhausted and overwhelmed'. Colin Robinson does not feed himself with human blood but with the energy of others. He drains humans and the other vampires' energy with his monotone, long conversations and boring nerdy character. He has a tedious office job, being the relatable, annoying co-worker who won't stop talking.

The show implements office culture with the character, as done by The Office. In one episode, he decides to drain people's energy through the internet, leaving racist and ignorant comments on social media to make people mad, portraying the role as the annoying internet user, in Dutch also called the 'zolder terrorist'.

Multiple vampires from cinematic adaptations and franchises are referenced and satirised

Finally, an exciting and unique aspect of the show is the fluidity of the characters in terms of sexuality. Nandor is confirmed to be pansexual, and Guillermo's actor, Harvey Guillen, has described Guillermo as Queer in interviews (Shipping Wiki, n.d.). The vampires Lazlo and Nadja are a married couple. Yet, admittedly, they have had affairs and have been intimate with Nandor and other people. Nandor and Guillermo are shipped by the fandom, and both the fandom and the actors are excited to see what is next for them. Their ship name is Nandermo, and there have been multiple hints throughout the seasons that their relationship is becoming romantic.

Considering all that has been discussed, it should be pointed out that the meaning of What We Do In The Shadows goes beyond the work's boundaries and the present. The hybrid fact-fictional content discussed in the last segment allows the audience to recognise and resonate with intertextual elements such as popular culture references and iconic vampire characters from other films and relate to the show by recognising things from their own life experiences. Likewise, the documentary format and the hybrid fact-fictional content create a relationship between the audience and creators. For example, the characters constantly interact with the camera by breaking the fourth wall and letting us, the people watching, in on their supernatural adventures and internal human struggles. This cultivates a sense of mediated intimacy. Like on The Office, another mockumentary show, the audience gets attached to the fictional people and their relationship dynamics. The audience feels involved and starts rooting for them.

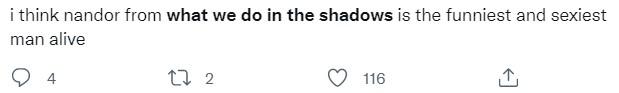

Figure 6. Tweet from a fan complimenting a character from WWDITS

Fans of the show can share online how they feel about the show and film and its characters and exchange meanings. It can sometimes become a parasocial relationship, a one-sided attachment with a mediated person. As shown in figure 6, this person tweeted about their love for a character in the show, the vampire character Nandor. The way they do it is similar to the way people tweet about celebrities.

Final thoughts

There are many more exciting elements of the film and show to mention. However, the paper's central question can be answered with the insights the above discussion has brought. The movie and the TV show spinoff cleverly play with the mockumentary genre so that all its functions are played out and explored while also questioning the form. The audience watches a sitcom in documentary form with its factual aesthetics. The filming and editing style of the film and the documentary codes in the show stand out especially and make the documentary form convincing. The documentary format makes it seem like they are real creatures living among us humans, which creates a strong audience-creator relationship.

Audiences are in on the jokes; not just comedy-wise, the characters comment on modern life, and thus the audience is also informed. The works are a hybrid fact-fictional form of cinema and TV. The narrative and the characters are invented but profoundly intertextual. Multiple vampires from cinematic adaptations and franchises are referenced and satirised. The writers also offer original takes regarding vampirical features and the characters' identity features. Likewise, despite its narrative being led by drama and comedy, the show is recognisable to people and builds a sense of mediated intimacy between the audience and creators.

Since the film and show are supposed to be in the same universe, the show could expand more on the characters and experiment with vampire traits and the vampires' histories and identities. The film and show have built a relatable universe where vampires are in the spotlight but also profoundly ridiculed and satirised. The audience follows how they struggle to adapt to the customs and values humans from the 21st century have after living for centuries. They try to make sense of modern life and technologies in which the audience is in on the many jokes and understands the commentary on reality. All the while, they deal with and fight with other creatures and make very human decisions.

The TV show is far from reaching its ending and enables the vampiric universe created in the film to be further explored. As season 4 is ready to air in 2022, What We Do In The Shadows fans can't wait to find out what else will happen and what or who is being referenced next.

References:

BAFTA Guru. (2019). Taika Waititi on Improvising "What We Do in the Shadows" & the TV Series | Screenwriters Lecture [YouTube Video]. In YouTube.

Boone, B. (2020, August 7). The Untold Truth Of What We Do In The Shadows. Looper.com.

Campbell, M. (2017). The Mocking Mockumentary and the Ethics of Irony. Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education, 11(1).

Cohn, D. (2000). The Distinction of Fiction. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Fhlainn, S. N. (2019). Postmodern vampires: film, fiction, and popular culture. Palgrave Macmillan.

Lewis, S. (2019, December 24). What We Do In The Shadows Vampire Character Inspiration Explained. ScreenRant.

Lipkin, S. N., Paget, D., & Roscoe, J. (2006). Docudrama and Mock-Documentary: Defining terms, proposing canons. In Docufictions: Essays on the Intersection of Documentary and Fictional Filmmaking (Illustrated ed., pp. 11–26). McFarland & Company.

Lyotard, J.-F., & Bennington, G. (2010). The postmodern condition: a report on knowledge (Vol. 10). University of Minnesota Press.

Nandermo. (n.d.). Shipping Wiki.

Masterclass staff. (2022, February 25). 3 Types of Comedy: Popular Types of Comedic Performance. Masterclass.