Brazil Online: The Public Sphere and Communicative Capitalism

This article will discuss whether it is possible to see a representation of the public sphere in online environments, and whether this online public sphere can lead to a more emancipated and organized society. The context of all this is a democracy where citizens use social media to mediate the public sphere, exchanging interactive information in real time.

Brazil Online: Potential for a Public Sphere?

Thus, the theoretical concept of the public sphere will be deconstructed and politicized, to make it applicable to current society. It is impossible to discuss the phenomenon of the public sphere without also talking about mass means of communication, such as social media.

This paper aims to connect the modern use of online media, as well as traditional media groups, and relate them to the same context of a communicative capitalism. This framework will be applied to the case of Brazilian internet and social media use as important tools that somehow mediate the public sphere, together with oligopolistic traditional media groups.

Among the literature discussed on communicative capitalism are Dean (2003), Why the Net is not the Public Sphere and Zizi Papacharissi (2002), The virtual sphere: the internet as a public sphere. The reality is that mass means of communication are controlled by big corporations, who own a big part of today’s internet. Moreover, Van Dijck (2013) explains that during the previous decades there has been a series of conflicts between different types of ideologies dealing with the internet as a public space. One of these ideologies tended to be more anarchist and revolutionary, while the other embraced the status quo proposed by neoliberal ideology, which later became known as the Web 2.0 ideology.

As for the Brazilian context, internet and social media have been crucial for the 2013 protests, the 2014 world cup, the presidential elections and finally the 2016 impeachment process, which ended with a massive victory for the right wing in the 2016 municipal elections. What once represented an ideal tool for political activism and exchange of information, free from media editorials, is now weak compared to traditional media groups and their recent impact on society.

What once represented an ideal tool for political activism and exchange of information free from media editorials is now weak compared to traditional media groups and their recent impact on society

In the end, social media proved to be the same as other traditional media corporations, full of algorithms, farms of fake news, clickbait, advertisements, personal opinions, egocentrism, echo chambers and dozens of other obstacles to the emancipation of the public sphere through free flows of information and opinions. The conclusion is that the only public sphere possible is the public space, which should be occupied and protected from privatisation.

Public sphere: the utopia and the ideology behind it

The ideas of ‘private’ (market and family) and ‘public’ (state) have been a constant in political theory. The idea of a public sphere, as theorized by Jürgen Habermas in the 1960s in his book The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, started a long debate on what the public sphere actually is, as well as the ideology behind this idea. Some current literature even questions if a public sphere can exist in contemporary society, especially in light of online platforms.

Habermas calls the act of agreeing and disagreeing communicative action: the multiple expressions of citizens’ ideas in real time confrontation, where one expresses his/her opinion and is responded to by others. Habermas derives his analysis from the bourgeois public sphere in 17 - 18th century Germany, where men from different social backgrounds would gather in coffee houses and have political discussions in a “fair and equalitarian environment”, similar to early Greek democracy. As Hobsbawm (1962) explains, this bourgeois public sphere was directly involved in the first mass means of communication: the newspaper.. The possible emergence of a bourgeois public sphere in these centuries is important in explaining many social revolutions that were the basis for the modern era.

The classical theory of the public sphere, by Habermas, is a nation-centred theory (Fraser, 2014). All the aspects of the Westphalian framework are embedded in this classical theory: the state-nation, the idea of one culture, one language, one nation, one economy and one mass media. According to Fraser, we should instead consider an international public sphere that goes beyond the nation-state centred one.

We should also claim subaltern public spheres, such as those of women, people of color, LGBT people, immigrants, and so on

Therefore, Fraser claims a post-Westphalian public sphere which utilizes the internet as its most advanced real-time communication tool. In the same way, as stated in in Rethinking the Public Sphere (1990), the idea of a public sphere should actually consist of multiple spheres. Whereas Habermas proposed the bourgeois public sphere, we should also claim subaltern public spheres, such as those of women, people of color, LGBT people, immigrants, and so on.

For Dean (2003) the public sphere “is the site and subject of liberal democratic practice, it is that space within which people deliberate over matters of common concern, matters that are contested and about which it seems necessary to reach a consensus” and she claims that the public sphere should also be reflected as an ideology.

Most of the utopian ideologists of the public sphere have applied this concept to new technologies of communication. This application was represented first by anarchic groups of cyberactivists, pirates and cyber-anarchists (Silveira, 2010). Creative Arts Ensemble (CAE), a collective that advocates direct action and civil disobedience online, states that many of these groups have succeeded in electronic civil disobedience (ECD).. Groups, such as CAE claimed that the public sphere would be driven by what takes place on the internet.CAE further claims that this should be done in a clandestine way, as to not expose their practices on the internet in light of online surveillance.

According to Papacharissi, the expression of a political opinion online may give one a feeling of empowerment. The power of words and their ability to effect change, however, is limited in the current political situation in Brazil. In a political system where the role of the public is limited, the effect of these online opinions on policy making is questionable.

The necessary communicative action as proposed by Habermas hardly works on Facebook

The idea of an internet-based debate is also questionable, and the necessary communicative action as proposed by Habermas hardly works on Facebook. The face-to-face is necessary when having a real debate (Miller, 2016), to ensure that the best argument wins. It appears that only when equals share a face-to-face conversation it is possible to have communicative action towards a consensus.

We can think about, student movement assemblies or workers’ unions voting whether to enter a strike or not as examples. In micro-spaces (such assemblies) we can see the public sphere working as it was conceived, but the same cannot applied to fragmented networks on the web. Papacharissi affirms that the internet allows us to shout loudly, but whether others will listen is questionable, and whether our words will make a tangible difference is even more doubtful.

For instance, Facebook's timeline, famous for creating echo chambers, shows that social media communication is fragmented in nature. Groups with mutual interests are algorithmically gathered on Facebook, in other spaces they might create private communities of members. Apart from group fragmentation, and the echo chamber effect, the massive amount of information encountered within a small amount of time on Facebook’s newsfeed is fragmented as well. We encounter algorithmically assembled opinions or factoids.

Social media users are merely passive workers for a profit driven content generation machine

Papacharissi affirms that we have “bits without organic integrity.” Also, when individuals address random topics, in a random order, without a commonly shared understanding, everything becomes even more fragmented and its impact is mitigated. The ability to discuss any political subject at random, drifting in and out of discussions and topics on a whim can be very liberating, but it does not create a common starting point for political discussion. Ultimately, there is a danger that these technologies may overemphasize our differences and downplay or even restrict our commonalities, as proved by the echo chamber caused by algorithms. In effect, social media users are merely passive workers for a profit driven content generation machine.

Communicative capitalism and the public sphere

“Internet guarantee access to the contradictory in a society where corporate media dominates the content shared. In internet, even in corporate social media, there is space for the contradictory, although this is not the ideal space and it is still embedded with the so-called communicative capitalism.” (Dean, 2003)

Mass media always evokes a fictional entity called “the public opinion.” This, helped by statistical research, would supposedly be able to express the majority opinion. So-called public opinion can be a challenge to political forces and can be used as argument by the powers that be, such as the corporate conservative media and traditional politicians. Conservatives in the Brazilian National Congress claim “The public opinion is with us” when voting for Dilma Roussef’s impeachment process or for the lowering of minimum penal age from 18 to 16 years, while displaying newspapers that corroborate their argument.

Members of the National Congress celebrating the victory of Dilma's Impeachment process, April 2016. On the signs, “Goodbye Dear!”

Communicative capitalism, as discussed by Dean(2003), supported by Manuel Castells’ arguments, is a useful theory that explains the powers in control of social media and the internet. Communicative capitalism represents an obstacle to political progress and emancipation, as communications in service of democracy are limited or barely regulated by the public power. Consequently, mass media represents the interests of corporations and profits from the commerce of information and culture.

This is central for the neoliberal ideology of consumerism. In corporate mass communication one will rarely see critical dissent challenging the establishment or status quo. Most of the time an individual is bombarded with advertisements. This can cause problems regarding the visibility of women, for example, and their representation. The same problem is doubled when it comes to racial issues.

The use of public opinion as an argument has always the hands of editors on it, which are certainly not neutral, and want to align the information broadcasted with corporations’ interests. This can include being against certain protests and policies that benefit minorities, and they can even contribute to the elections of certain candidates. Additionally, corporate mass media isdirectly connected to advertisers and they avoidpublishing news that might discourage advertisers, even if they are the gun, tobacco or alcohol industries.

The use of public opinion as an argument has always the hands of editors on it, which are certainly not neutral

Considering the current reality of easy access to new media, the internet, and social media , one could affirm that the public is self-appropriating from these new corporative means of communication, producing and sharing their own information. Thus, freeing themselves from the hands of traditional mass media, they use emancipatory means of political discussion enabled by the internet where face-to-face is not needed and ample access of information is guaranteed.

It could also be argued that, different from the traditional means of communication, social media and the internet enable citizens to be in control of what it is shared or posted. Or that it is a dialogical way of getting useful information, because it also empowers them to share and give visibility to subalterns. The internet provides users with the illusion that they are part of one dialogical public sphere which can allow them to achieve political emancipation. Expression as a citizen started to be equated with expression on social media. The example of changing profile pictures on social media in solidarity in the context of political disputes is an example of this.

Users communicate on social media controlled by the biggest corporations, which induce them to engage in behaviours such as massively clicking the “like” button to make some contents more profitable thant others. It's important to re-emphasise that those corporations use and sell our personal information for profit as much as it profits from the content we're sharing inside its network. Users of social media act as human experiments of big data.

Communicative capitalism is not disembedded from big internet portals (Yahoo, Google, etc) or social media, but users appear to be ideologically blind to it. There are, however, some cases of struggle against it, such as the Creative Arts Ensemble, WikiLeaks, Wikipedia, Creative Commons, Pirate Bay, Laws of Civic Regulation of Internet (as L.12.965 in Brazil), The Flok Society and the Open Government Partnership initiative. We can find numerous independent media groups that work together with social media and outside it. Famous cases are Media Ninja and Jornalistas Livres, from Brazil. This process of privatisation of the internet from companies and governments doesn't happen without contestation.

The Brazilian case

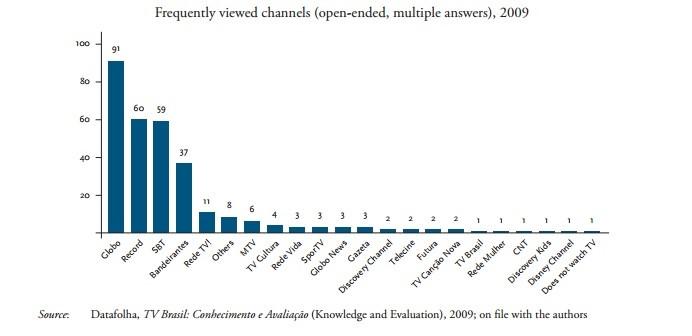

Before talking about the rise of the internet as a widespread means of communication in Brazil, it is worth talking about the the military dictatorship that took the power in 1964, and how it saw television and mass media as a political force to create national identity and spread political information. The military granted much of this power over television and radio to the businessman Roberto Marinho and his mostly monopolistic group, Rede Globo.

Rede Globo was deeply involved in many political manipulation scandals (the 1989 election, among many others), fiscal evasion, and openly supported the military dictatorship. More recently it broadcased of all the demonstrations in favour of Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment process, barely broadcasting those against it. It has until recently been one of the most influential media groups in Brazil, mainly through Jornal Nacional (National Journal).

Lately, Rede Globo has been losing audiences to the other five corporate TV Channels. Rede Record, one of the biggest, is controlled by Edir Macedo, a businessman and high priest of the Universal Church who has been widely criticized for charlatanism. In general, Brazilian television has been highly oligopolistic since the 1960s.

The rise of the internet changed the whole context of communication in Brazil.

The rise of the internet changed the whole context of communication in Brazil. Brazilians gained access to the internet on a large scale at the end of the 1990s. The first tools of communication, usually with modem connections by free providers, were the chat rooms, MSN messenger, ICQ, online forums, community websites, photologs and blogs.

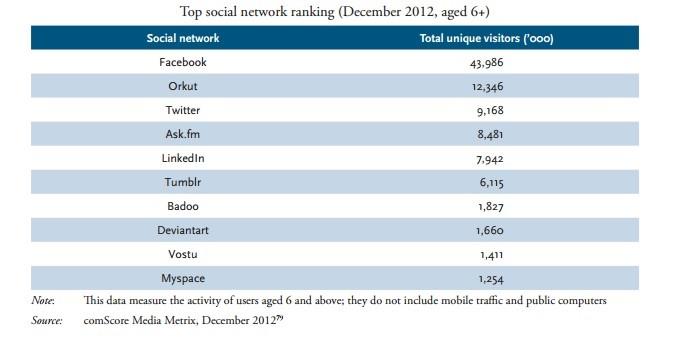

Orkut, the first wide spread social media website in Brazil, was founded in 2004 by the Turkish programmer Orkut Büyükkökten and later bought by Google. While at first it was a small US/English-speaking community of invited users, it was taken over by Portuguese-speaking Brazilians(Fragoso 2006). In this social media site, you could add friends, create your own network, leave comments on others’ pages, add pictures and participate in different “communities”. In general, Orkut was very much like a predecessor of Facebook.

Socio-economically and politically, 2002-2010 in Brazil was characterized by Lula’s governments and economic and human development growth related to Partido dos Trabalhadores (workers party) governments. The country accomplished an increase in welfare state policies, which would also increase the strength of capitalism in an economy based on construction, telecommunication and export of commodities. This would facilitate the acquirement of means of consumption for regular workers with the increase of the minimum wage, credit, and social programs of income transference such as Bolsa Familia (Singer, 2012).

A new and massive middle class emerged with access to new techonologies like computers and smart phones. Both the socio-economic context and previous online experiences, caused a massive increase in social media users in Brazil. Brazilians are one of the biggest groups on the internet, with 89 million users, which is 45% of the population. A study conducted in 2004 by IBOPE/Netrating stated that Brazilians spent more time on the internet than the average American user.

From Mapping Digital Media in Brazil (Open Society Foundation)

According to a study published by the Open Society Foundation, Mapping Digital Media in Brazil, regarding User-Generated Content (UGC):

“Brazilian web culture is heavily driven by the consumption of content published or found through web portals, and the use of a variety of social media. Four of the 10 most visited websites in Brazil in September 2013 are primarily UGC (Facebook, YouTube, Mercado Livre, and Wikipedia); another four are web portals (UOL, Globo.com, Live.com, and Yahoo!). The remaining two are Google search domains (Google.com.br and Google.com).”

The same study emphasises the role of media networks as a means for digital activism and political participation for Brazilians, showing a detailed summary of recent political manifestations using social media.

Internet users go for social media and online content as refugees from a land dominated by traditional oligopolies of communication

Brazilians use the internet for everything: entertainment, information, political activism, and commerce. In a country without public regulation of the media, a few oligarchical families control media such as newspapers, radio, television channels and big internet-based companies.Most of them share the same neoliberal and conservative ideology of a country ruled by big corporations, are deeply involved in corruption scandals and were a main force in the recent coup d’etat of 2016. Thus, users go for social media and online content as refugees from a land domainated by traditional oligopolies of communication.

From Mapping Digital Media in Brazil (Open Society Foundation)

Social media has been appropriated by the public administration, as big cities' municipalities show, such as Prefeitura de Curitiba. As have social movements like Frente Brazil Popular and Frente Povo Sem Medo. It was critical for the 2013 protests, 2014 world cup, elections, and now protests for and against the what many Brazilians consider to be an illegal coup d’etat disguised as an impeachment process.

Therefore, the internet has a central role in Brazilian political activism. Many spontaneous protests are organized via social media and it is a way to inform people when are where protests are taking place. Although participation in street protests has been massive, slackctivism in Brazil is also an alarming reality. As a result, some citizens are compelled to forget that it is even possible to organize themselves politically outside social media occupying the public space.

Yet, this appropriation of social media by citizens, politicians, and public figures is not seen with critical eyes. For instance the so-called echo chambers of algorithmic social media are hardly discussed by social media users. Social media imposes dozens of obstacles to political organization and this should be a constant debate.

Relying mainly on social media for political activism and citizenship in democratic societies in the times of post-truth democracy is an illusion

Relying on social media for political activism and citizenship in democratic societies in the times of post-truth democracy is an illusion, as argued above regarding fake news, algorithms, and echo chambers. It is necessary to politicize the debate surrounding the adoption of social media as a tool to mediate the public sphere. There should be more education about what the World Wide Web, social media groups, and the Web 2.0 actually are, and how they are impacting cultural and political behaviours regarding citizenship and democracy. After all, social media and internet groups are just new and stronger communicative capitalist corporations willing to profit from our information and data.

Conclusion

The discussion involving the public sphere and use of the internet has been latent in political theoretical debate. Still, it is important to bring it back, as it illustrates how democratic debate can take place and how it is affected by the means of communication. Whenever technology provides a new means of communication, such as the internet and social media, the theory of public sphere should be brought to our attention.

Especially when considering super-diverse globalization, the analysis of the public sphere should be of the international public sphere, as proclaimed by Nancy Fraser in the Transnationalizing the Public Sphere. The idea of a public sphere should not be that of a nation centred one, with citizens who share a single language and culture.

We should also analyse critically how communicative capitalism acts in the mediation of this potentially international public sphere. It is important to analyse the use of internet and social media networks, as supported by data from the Brazilian case.

The higher the clicks and shares, the higher the profit

Social media affect the behaviour of users by engaging them in clickbait activities. The higher the clicks and shares, the higher the profit, therefore content is created to be appealing for higher profits, resulting mostly in lower quality content, such as fake news. The nature of social media is that of the neoliberal ideology of consumption.

In a time of crises, the profits of social media companies are exponentially rising. The network of Big Data is a tool of reification of subjects and increases the power of corporate capital. Blindly ignoring social media as important players in contemporary capitalism is harmful for political participation. One cannot trust everything on social media when acting politically. Social media and the internet cannot be confused with public space.

The nature of social media is of the neoliberal ideology of consumption

Even considering the visibility of subalterns on social media, such as feeling empowered to share information that could increase emancipation and social justice, it is still not the ideal debate that allows one to engage him/herself in a political conversation among other citizens. There is no democratic legitimacy in the use of social media. They can provide certain benefits to the spread of valuable information, but their dark side also has to be critically evaluated.

Algorithms contribute to an even bigger fragmentation of information, debate, and dissent. The echo chambers and algorithms tend to create social media environments more appealing for users, as they are more likely to engage with posts and information that are calculated to be precisely linked with the user’s information. No one’s results of Google search are the same.

It is not with slackactivism that citizens engage themselves politically in the public sphere

It is not with slackactivism that citizens engage themselves politically in the public sphere, as the impact of social media is mitigated by poor dialogic conditions. The time-line logic does not allow proper political communicative action, just a flow of information that people like, dislike and share, generating more data for corporations and making them each day a more lucrative company. Not often do we see evidence of public use of reason, but instead trolling, cyberbullying and flaming. The non-face-to-face encounter is disembedded of ethics (Miller, 2016).

The revolution will certainly not be televised, nor liked, maybe shared, and social media will not be the centre of revolution. The representatives of Inside Dreams, a social movement from USA related to Black Lives Matter whoopenly left social media for a certain period, state: "one can use social platforms, but the real work is the praxis with the movement’s basis. The only ultimate place for the public sphere is the public space, just in fair situation of communicative action citizens can reach an ideal public debate. Public spaces, per se, should be occupied by citizens, preserved and prevented from being privitised."

References

Critical Art Ensemble. Electronic Civil Disobedience, Simulation, and the Public Sphere. In: http://www.critical-art.net/books/digital/

Dean, Jodi 2003. Why the Net is not a Public Sphere. Constellations 10 (1), 95-112.

van Dijck, José 2013. The Culture of Connectivity. A Critical History of Social Media. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fragoso, Suely Dadalti 2006. WTF, a crazy Brazilian invasion. In F. Sudweeks & H. Hrachovec (eds.) Proceedings of CATaC 2006. Murdoch, Australia: Murdoch University Press.

Fraser, Nancy 1990. Rethinking the Public Sphere. Duke University Press.

Fraser, Nancy et al. 2014. Transnationalizing the Public Sphere. Polity Press.

Gill, Rosalind 2007. Postfeminist media culture. Elements of a sensibility. European Journal of Cultural Studies 10 (2), 147-166.

Habermas, Jürgen 2011. Mudança Estrutural da Esfera Pública. Editora Unesp.

Miller, Vincent 2016. The Crisis of Presence in Contemporary Culture. London: Sage.

Morozov, Evgeny 2011. The Net Delusion: How not to Liberate the World. London: Allen Lane.

Papacharissi, Zizi 2002. The virtual sphere: The internet as a public sphere. New Media & Society 4 (1), 9-27.

Silveira, Sergio Amadeu 2010. Ciberativismo, cultura hacker e o individualismo colaborativo. Revista da USP, n. 86.

Singer, André 2012. Os Sentidos do Lulismo, Reforma Gradual e Pacto Conservador. Companhia das Letras.