How the VVD party’s ‘warm right’ convinces ‘the people’

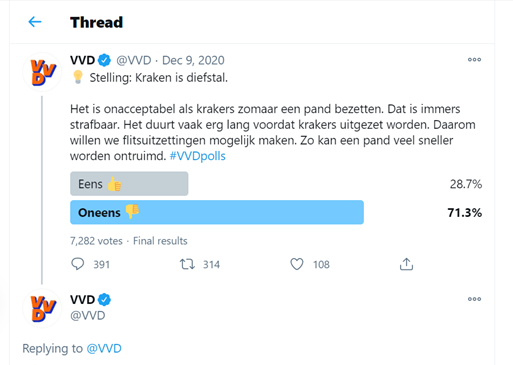

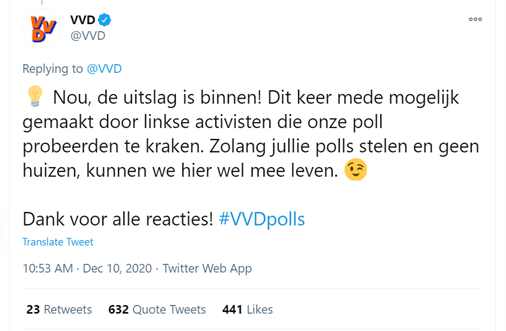

In December last year, the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) launched a poll on Twitter which had an unexpected outcome. In this poll, the party asked netizens if they agreed with them that squatting is theft. Of the more than seven thousand participants, over seventy percent disagreed with them. VVD replied they believed the poll was hacked by ‘left activists’, saying ‘as long as you steal polls instead of houses, we can live with it’. Twitter held up a mirror for the neoliberals in the comment section: ‘exactly who has been in power for the last decade, causing major housing shortage?’

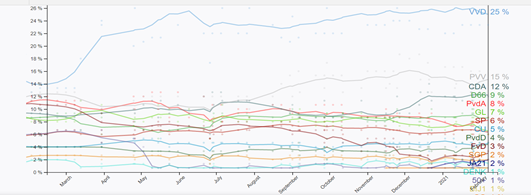

The People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy has been the biggest party in the Netherlands since 2010, and is led by prime minister Mark Rutte. Their neoliberal ideology of tax reductions, a market economy and laissez–faire causes them to be known as a party for the rich and the big corporations. Because of the Dutch childcare benefits scandal (toeslagenaffaire) in which false allegations of fraud were made against thousands of Dutch families, the current government led by the VVD has fallen.

The VVD is by far the highest in the polling, despite many scandals.

Despite being the party with the most integrity scandals for the eighth time in a row, the VVD has been the leading party in the Netherlands since 2010 and will remain so according to the polls. This paper contemplates the political message of the VVD and tries to answer the question how it has persuaded the working and middle classes to vote for them. Analysing the ‘message’ (Lempert & Silverstein, 2012) using multimodal analysis, I will try to shed some light on the political strategies of the VVD. Data were retrieved from mainstream social media and running Tweetdeck #VVD @minpres and various other hashtags and public profiles to analyse the message the VVD party presents in the hybrid media system.

Gravitating towards the default

The People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) has a very effective political strategy in which it frames itself as ‘the normal and the responsible’. Prime minister Rutte communicates a kind of ‘ruler of the country but still a normal guy’ message which is 'crafted out of issues rendered important in the public sphere (Lempert & Silverstein, 2012: 2)'. The simple fact that Rutte goes to work by bike indexes the prime minister is ‘just like everybody else’ who has to go to work and that he (and his party) value the climate. It is ‘normal’ to value the climate, because ignoring climate change is ‘irresponsible’. The prime minister also teaches civics on Thursdays at a secondary school in The Hague, which complements this message of being ‘one of the people’.

The People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) has a very effective political strategy that makes them ‘the normal and the responsible’.

The VVD chooses to ‘identify a competitor that deals with dangerous issues to be kept at a distance’ (Lempert & Silverstein, 2012:2), which is far right politician Geert Wilders (PVV), who is not deemed capable of governing, because ‘’the Party For Freedom makes horrible statements about entire groups in The Netherlands’’ (AD, 2021). ‘De–islamisation and ‘fewer, fewer fewer Moroccans’ (statements from Geert Wilders), we are not going to govern with that’, VVD member of parliament Bente Becker said in a TV show. De–islamisation and arguing for ‘fewer Moroccans’ are the dangerous issues VVD wants to keep at a distance and Wilders is the politician to be identified as the competitor.

Another politician who is ‘not normal’ in the political discourse of the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy, is Thierry Baudet (Forum for Democracy, FVD). Recently, some racist messages from FVD members were leaked in which Baudet mocked several minority groups, to which the prime minister responds: ‘’those horrible Whatsapp messages fit in the image we see of him, but it has become impossible to govern with him (Baudet)’’ (AD, 2021).

The party has the hybrid media system on its side ‘tapping and steering the information flows in ways that suit their goals’ (Chadwick & al, 2016:4). Politicians try to get portrayed in the mainstream media in the way they want people to see them. Social media (which is part of the hybrid media system) is staked on neoliberal principles, which translate into the valuing of hierarchy, competition and a winner–takes–all mindset (Van Dijck, 2013: 21).

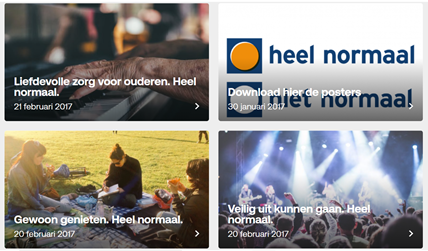

By repeatedly using the words ‘normal’, often in combination with ‘very’ and ‘abnormal’, the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy communicates that voting for them is the only rational thing to do (Allan, 2010). During the previous elections, VVD had a campaign that prominently featured the slogan ‘very normal’, which further illustrates this point.

Acting normal. Just be normal.

According to Marx and Engels, the capitalist ruling class needs to present its ‘ruling ideas’ as being consistent with the beliefs of ordinary people (which includes both the working and middle classes). For this 'they need to present their ideas as the only correct, rational opinions available to them' (Allan, 2010: 48, Marx and Engels, 1845: 65 - 6). VVD uses a communication concept in which their statements are combined with the words ‘very’ and ‘normal’, which then normalize their statements. Note the full stop after every statement and the bold font which says: this is how it is, plain and simple. The challenge for the political class (and thus for the VVD) is to keep people loyal to the neoliberal ideology. Therefore 'an issue for them is the degree to which the masses can be co-opted through various methods to support the status quo' (Kofas, 2019: 2).

Respecting the police is very normal.

The poster above argues it is ‘very normal’ to learn at home that the police has to be respected. Each mode in this poster (colour, writing and image) has a function (Kress, 2010:1). The aim is to normalize the ideas of the VVD. The image (the ‘poll’) points to the dichotomy normal versus not normal. Using this ‘poll’ below their statement complements the ‘normality’ of the statement. The font used is always the same one for the party: bold and no nonsense, which also complements the idea that the only rational option is the VVD. The colours used (blue and orange) index nationalism and (neo) liberalism. Orange is the national colour of The Netherlands and blue is the colour of the political right, in the same way the socialist colour is red. These colours are used to highlight specific aspects of the overall message (Kress, 2010:2). Voting VVD is a normal thing to do for Dutch citizens, it says. The poster also appeals to nationalist voters. Without using any words, the VVD indexes a strict migration policy with this poster. ‘We are the Dutch, and if you disagree with us, you’re not one of us’.

The neoliberal ideology speaks to 'the people'.

By offering the illusion to the marginalized that they are going to be integrated into the mainstream or elite discourse, while trying to indoctrinate them with the idea that the corporate state is good and the welfare state bad, the neoliberal ideology speaks to the people (Kofas, 2019). In this way 'they have captured the imagination of many middle class and even some working class people' (Kofas, 2019:7). This normalisation of their statements through their style of campaigning might be one aspect that explains the success of the Dutch prime minister and his VVD.

‘Warm right’ to appeal to as many voters as possible

The People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy selectively chooses some issues with which they identify themselves and their ‘warm right’ discourse. In this case, these issues are to support entrepreneurs, to keep the country as safe as possible, and a ‘war on squatters’. By focussing on these topics (safety, entrepreneurship and squatting), VVD members of parliament ‘acquire a political persona’ (Lempert & Silverstein, 2012) as they are to be seen as ’the tough protectors of property’. This protecting of property also shows in their very frequent and gaudy ‘support of the local entrepreneurs’. This sounds like the party wants to save small businesses, but it really means protecting the economy rather than the people.

Buy locally 'like me' to help the local entrepreneurs.

The ideology of consumerism is disguised as ‘supporting your locals’. This appeals to both (local) entrepreneurs and to other citizens, and plays into people's feelings with statements such as ‘your support can be the drop to make it this month’ and ‘buy locally like me’. With other words: ‘If you buy (locally) you support others’.

With their current campaign ‘our new story’, the party responds to (other) populist parties using both (extreme) right statements (to penalize illegality) and even leftist statements (higher minimum wage) to reach as broad a voting audience as possible. They move along with the growing popularity of extreme right and populist parties by encapsulating some (extreme) right ideologies in their own election campaign. Meanwhile they also fill the gap between them and the left parties which shows to the voter that they have listened to everyone. ‘Instead of decreasing the role of the government, an active and subservient government is required in these hard times to protect us and to keep our economy and society fair and healthy. Freedom, responsibility and reciprocity are important guiding values.’ (VVD, 2021: 5).

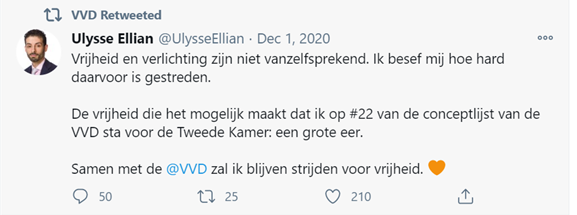

These values resemble the values from radical enlightenment, but in slightly altered form: freedom, equality and brotherhood becomes freedom, responsibility and reciprocity. By putting emphasis on individualism and freedom, the VVD’s values are hegemonic. Freedom, responsibility and reciprocity seem ‘normal’ and ‘neutral’ (Diggit, n.d.), but they actually refer to a specific ideology in which responsibility is valued over equality. A clear ideological direction has been chosen in which individualism is just a simple fact of life.

Freedom and enlightenment are not obvious chairman Ellian says.

In the Tweet above, a regional chairman of the VVD party actively refers to enlightenment and freedom in the context of enlightenment. The long historicity of these values give the party extra credibility, because they are hegemonic.

Combatting squatters while ‘doing a Trump’: populism through polling

In times when there’s a need for more housing, the VVD is ‘the protector of property for those who already own’ when they open fire on squatters. With retweets, shares and likes, the populist can make the populist claim that they speak on behalf of ‘the people’ (Diggit, n.d: 2). When VVD launches polls on Twitter (#VVDpolls) ' it is not only for the frame that actors prepare for uptake' (Maly, 2020:2) but the work done by the netizens interacting with the polls as well. The polls are not only for finding out what people think about a certain matter (like squatting) but also to show other netizens how much people agree with them. Twitter becomes the 'digital media infrastructure through which the message is distributed and knowledge about the audience is gathered' (Maly, 2020:2).

VVD poll on squatting. Most voters disagreed with them.

What becomes clear in the party's polling about squatting, is that 'some kind of legitimation and recognition of ‘the people’ is being asked', (Maly, 2020:2), and obviously this is not given in the example above. This led the VVD to respond that the ‘poll must be hacked by left activists’.

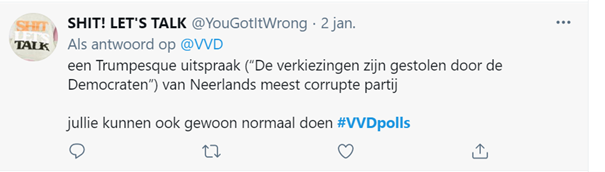

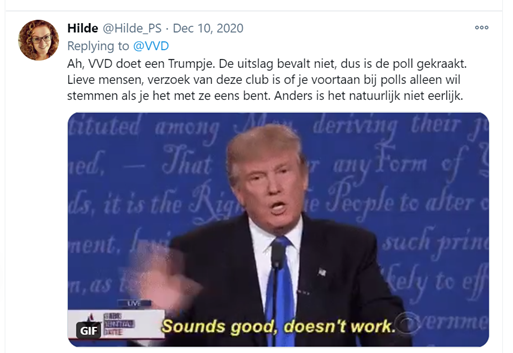

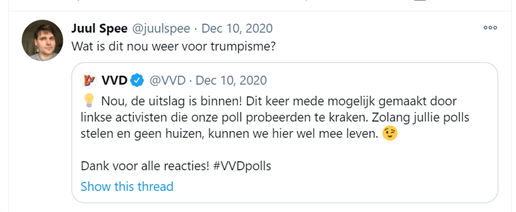

VVD Trump move

Below an example of a Twitterer contributing to VVD’s message in the hybrid media system. Referencing Trump it responds to VVD’s ‘normal’ message: ‘A statement in the style of Trump ‘the elections are stolen by the democrats’ from Netherlands’ most corrupt party’ and then: ‘you can also just act normal’. Acting normal is the main message of the party. The Twitterer uses the political discourse of the party to attack it on its own terms. 'Campaigns can use hybrid strategies to both capture citizen input and mobilize citizens for campaign, but citizens can also subvert campaign messages using digital media'. (Chadwick & al, 2016).

A 'Trumpesque statement of The Netherlands' most corrupted party'

Multiple people started making comparisons between Trump and the VVD's response to the results of its own poll. The party decided to not have these replies removed, which could ironically also be seen as being normal, because everyone makes mistakes.

VVD does a Trump move.

What kind of Trumpism is this?

Neoliberalism during pandemic times

By putting major emphasis on the dangers of the Corona virus while calmly but firmly explaining the Covid measures, prime minister Rutte ‘messages’ that he is the calm and stable leader people need during a pandemic; the decisive man of the nation who is not hasty, aggressive or impulsive. He acts ‘decently’ and responsible, like his party.

Despite the childcare benefits scandal, the People’s Party of Freedom and Democracy leads the polls by a wide margin, which might in part have to do with Rutte’s conduct during the Corona crisis. The entire organisation, look and way of presentation is part of the prime minister's message, which portrays him as the guardian of the people. Because the prime minister is coherent in his message, no votes were lost despite the childcare benefits scandal.

The strict policies against Covid contagion taken by the Dutch government seem in contrast with neoliberal thought, but derive from an old model of dealing with disease. This is why VVD can impose strict measures like the notorious evening clock and the closure of all bars and restaurants for half a year, without losing credibility as being liberal. ‘The purpose of the plague model was to prevent the spread of contagious diseases by imposing a strict control on the circulation of bodies. The management of the plague gave rise to disciplinary projects which are similar to the measures taken today’ (Kakoliris, 2020).

Despite the controlling measures, the VVD did not lose credibility.

This means that despite the controlling measures, the VVD did not lose credibility because the way they deal with Covid is conventional and established. In fact, this even contributes to the message of the prime minister, of being a responsible, thus normal leader.

Conclusion

The People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) has been in charge for the past decade in the Netherlands and it looks like they will remain in charge. Despite the childcare benefits scandal and in part thanks to their conduct in the Covid crisis, the party is doing better than ever. This is likely the case because they have successfully used the hybrid media system to deploy their message and by connecting this message with what we find ‘normal’, with ‘common’ sense. What is also to their advantage is the fact that social media is already built on neoliberal principles. Their new election campaign ‘warm right’ is designed to address as many voters as possible by adopting popular statements from the political left to the political (far) right without ‘going off message’. In this way the party remains credible, even in (or perhaps even thanks to) the current pandemic and the economic crisis that is likely to come.

References

Allan, S. (2010). News Culture. McGraw – Hill Education.

Chadwick, A. Dennis, J. & Smith, A.P. (2016) Politics in the Age of Hybrid Media: Power, Systems and Media Logics. In: Bruns, A. et al. (eds). The Routledge Companion to Social Media and Politics. Routledge.

Van Dijck, J. Poell, T. & De Waal, M. (2013) The Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World. Oxford University Press.

Diggit Magazine (n.d.). Algorithmic Populism. Diggit Magazine.com. Retrieved from: https://www.diggitmagazine.com/wiki/algorithmic-populism

Diggit Magazine (n.d.). Hegemony. Diggit Magazine.com. Retrieved from: https://www.diggitmagazine.com/wiki/hegemony

Kakoliris, G.(2020). A Foucauldian enquiry in the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic management (Critique in Times of Coronavirus). Critical Thinking.com. Retrieved from: https://criticallegalthinking.com/2020/05/11/a-foucauldian-enquiry-in-the-origins-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-management-critique-in-times-of-coronavirus/

Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. London: Routledge.

Kofas, J. (2019) Neoliberal Totalitarianism and the Social Contract. Research Gate. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331876517_Neoliberal_Totalitarianism_and_the_Social_Contract

Lempert, M. and Silverstein, M. (2012) Creatures of Politics: Media, Message and the American Presidency. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Maly, I. (2020). Algorithmic Populism and the Datafication and Gamification of the People By Flemish Interest in Belgium. Trabalhos em Linguistica Aplicada. Vol 59 (1). Doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/01031813685881620200409