The post-normal era, uncertainty, and irony politics

Imagine growing up in an era when facing crisis after crisis is normal and truth is negotiable, where capitalism is the default and crisis is a normal state of being. When everything new becomes immediately normalized, we create our own abnormal ‘normal’. The ‘incubation time’ from new to normal is getting shorter and shorter, and irony politics only greases this slippery slope.

This paper argues that the COVID-19 pandemic has increased both distrust in politics and the influence of social media platforms, especially during long lockdowns. It will be argued that the corona-crisis has accelerated change, while at the same time increasing denial of change. Additionally, crisis fatigue (Flinders, 2020) as a socio-political phenomenon has caused distrust in institutions while at the same time making (especially young) people fed up with the constant reminders of doom.

By looking at (ironic) responses to political messages and polls on platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and 4Chan, it will be demonstrated that politics have become a joke rather than a serious endeavour due to post-normalcy and pandemic fatigue.

Normalization of change

We are in a moment of profound change. Within a year, everyday public life has nearly vanished. The ways we communicate, work, play, and learn have become digitized; nearly all of our daily activities happen online. Online space itself has also changed under influence of the coronavirus pandemic: we not only profile ourselves as politically left or right on social media, but we also profile ourselves as pro – or against COVID measures. We are witnessing the normalization of crisis in both online and offline spaces. We are now going ‘post’ phenomena more and more rapidly, to the point that face masks are now a part of fashion retail. Facemasks have only been compulsory in The Netherlands since December 2020.

A Facemask Store

Stores like these show how quickly things are normalized. Postnormal times theory (Mayo, 2020) could explain how changes come to be normalized so quickly, as it ‘’proposes the current epistemological crisis is a cultural crisis in which our desire to ‘make things normal’ fundamentally expedites a sense of crisis’’ (Mayo, 2020, p. 2). It can be seen as a sort of cognitive dissonance to not have to feel the ‘crisis’ part of the corona crisis. Everything has the potential to be ‘truth,’ depending on where you stand.

Because every platform on the internet, every corporation, every government and every institution have shared their ideas on the corona crisis, the expert has died. Experts have become ‘just one out of millions of voices’ with something to say about the virus. When everyone in every authoritative societal position has an opinion about something, it becomes very difficult to decide which stance is most truthful.

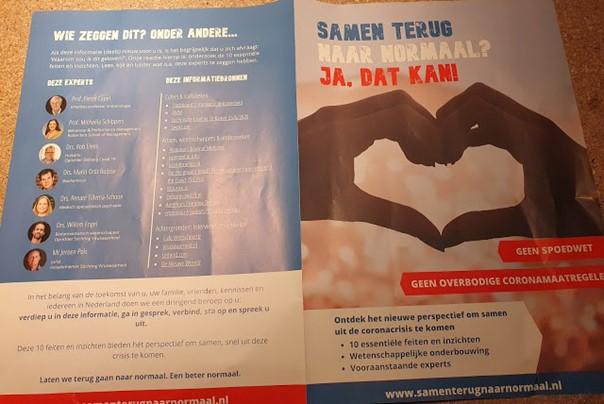

Alternative experts from Viruswaarheid (Virus truth), a movement that protests against the Covid measures in The Netherlands.

'Post-normal times' is a period in which ‘old ways of knowing are eroding and new ones are yet to emerge’ (Mayo, 2020, p. 2). We know that the current ways in which we deal with globalization and climate change are not sufficient to create a stable planet, but we have not yet developed new ways of knowing around the coronavirus - we cannot yet imagine a post-corona society.

Both crises and change are normalized.

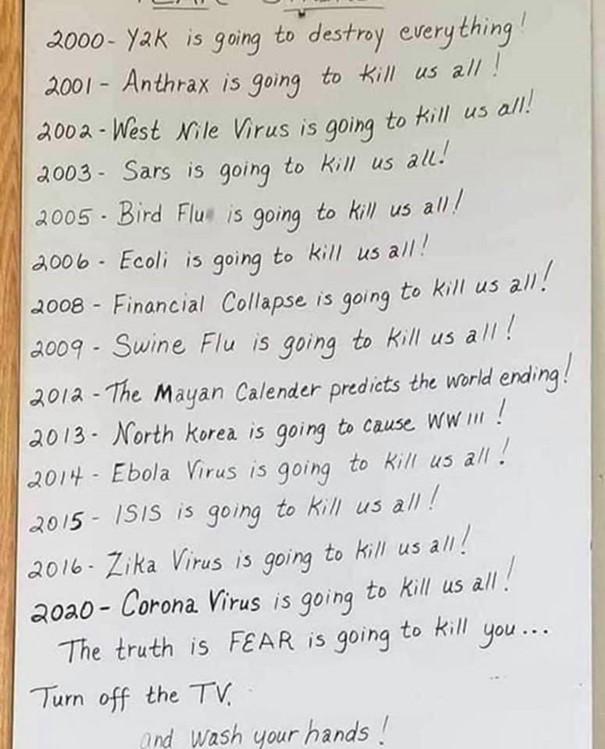

Our rapid-normalizing, post-normal times are characterized by ignorance and uncertainty (Mayo, 2020), in which ignorance causes uncertainty, and normalization camouflages the cognitive dissonance we experience because of this uncertainty. Another explanation for how we are able to adjust to these new circumstances this fast, is because ‘crisis fatigue’ in which ‘the public has simply become immune to warnings from politicians and people habitually become distrustful of their claims’ (Flinders, 2020). We have become tired of all the warnings crises and disasters of the past twenty years, and our post – normal uncertainty has made us tired and cynical. This means that both crises and change are normalized, which also shapes the way especially the younger generations look at politics.

Two decades of crises from Sars to Covid.

It is logical to distrust governments and political institutions if all you hear is crisis. Aksoy and colleagues (2020, p. 1) argue that ‘epidemic exposure in an individuals’ ‘impressionable years’ has a persistent negative effect on confidence in political institutions and leaders.’’ This ‘extra tangible’ crisis combined with the uncertainty of post-normality and constant anxiety fatigue is the ultimate recipe for irony politics.

Irony politics

When old paradigms are dying and new ones have not yet arrived, irony can be both a coping mechanism and a way of showing dissatisfaction. Every political strategy has failed, leaving us with nothing but sheer capitalism. Margaret Thatcher’s ‘there is no alternative’ seems even more accurate today than in the eighties. Citarella (2019) argues that "To insulate oneself from seemingly guaranteed failures, Millennials and Gen Z adopted irony as a cultural strategy." Having learned that there is nothing but crises and capitalism behind politics, young people do not seem to take politics seriously anymore.

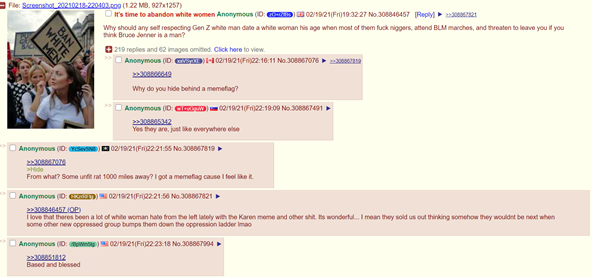

In the post below, an anonymous poster on 4Chan asks, "why should any self-respecting Gen Z white man date a white woman his age when most of them [profanity], attend BLM marches, and threaten to leave you if you think Bruce Jenner is a man?" This is asked in an ironic way or ‘rhetorically’, but displays an extremist right-wing view that includes racism and transphobia.

A 'Gen Z man' on 4 Chan.

Irony is not apolitical. Today, ‘meaning is sought by everyone, everywhere, even at the extreme fringes of the political left and right’ (Mayo, 2020, p. 5). For the youngest voters, meaning is sought at the fringes of the political spectrum. The COVID-19 pandemic has only sharpened this effect.

In January 2021, the Socialist Party (SP) in The Netherlands was headed towards a break-up with their youth division, ‘rood’ (red). The party argued that young members could not elect a chairman that was ‘too radicalized’. At least four members were expelled by the parent party for being ‘radicalized attic communists’. Meanwhile, the media reported about juvenile extremism on the other side of the political spectrum - youths from the (extreme) right-wing Forum voor Democracy (FvD) had spread antisemitic conspiracy theories on social media.

'conspiracy post' on 4 Chan: a message board where many young people are active.

Citarella (2019) argues that Gen Z’s political irony is far from meaningless or ‘just for fun’, because "ironic propaganda functions the same as real propaganda and ironic voting is just voting." He proposes an arc of online politicization in which youth go from apolitical to radicalized under the influence of the internet.

In itself, shitposting has nothing to say

At first, teenagers are apolitical until ‘things get worse’, i.e. a crisis, declining wealth, or a pandemic. Feelings of distrust start to dominate in an attempt to find explanations for their grievances. They then realize that the mainstream narrative might not have the answers, but might actually be the problem. After that, ‘shitposting’ occurs. 'Shitposting' used to be ‘a way of proposing ideas that existed potentially outside the bounds of the Overton window’ (Citarella, 2019), but has now become part of identity play. In itself, shitposting has nothing to say, even though some shitposters have been connected to terrorist attacks. The aim of shitposting is to derail a discussion or to simply provoke. As a side effect, the new narratives it creates can actually start new political discourse.

'eat shit' bread tube.

In this image the poster mocks ‘the left’ and Bread Tube, a loose group of left-wing content creators. The post remarks on Biden's opening of a new facility for migrant children; migrant facilities caused a lot of protest and controversy during the Trump administration. This is a triumphant response from the (far) right - the crying figures in the image wear a ‘Bernie beanie’ and a cap with the communist symbol.

Mocking 'the left'.

Growing up in an era of crises, many young people start looking for an enemy. When the mainstream no longer has the answer, they start looking to the political fringe. According to Citarella (2019), after shitposting, teens become "susceptible to new narratives." The irony that follows is a way of adopting new narratives. By pretending they are joking, they can create a distance between themselves and current events while adopting a new narrative.

Funny politics

The clip above shows Minister of Justice and Security Ferd Grapperhaus dancing to Haddaway’s song "What is Love." Next to the video, the account declares that they "do not want to ridicule anybody; it is just a joke." Nevertheless it is ironic and indicative of not trusting political figures because ‘catchy aesthetics can transmit ideas that make you laugh first and radicalize later" (Citarella, 2019).

According to Citarella (2019), once a new narrative is adopted, the way is open for radicalization. For young people, the ‘neoliberal middle’ is not going to solve declining wealth, pandemic uncertainty, and crisis normality. Especially in democratic countries, "epidemic exposure in one’s impressionable years leads to declining trust" (Aksoy et al., 2020, p. 38). Add to that constant messages of climate disaster, financial crisis, and pandemics, and it becomes apparent why online politization occurs.

Conclusion

In a world where certainty and truth are a matter of opinion, crises have become normal, and governing beyond the ‘neo-liberal middle’ has become unimaginable, a pandemic can lead to political scars for a whole generation. Previous generations handed the latest a world in danger, younger generation started playing with new political narratives. They do this by using irony as a mechanism for both the normalization of new narratives and to keep a distance between themselves and the negative events around them. The current corona pandemic has made young people fed up with crises, causing immunity to warnings instead of viruses.

References

Aksoy, C.G. Eichengreen, B. & Saka, O. (2020). The Political Scar of Epidemics. National Bureau of Economic Research, working paper 27401.

Citarella, J. (2019). Irony Politics & Gen Z. New Models.

Flinders, M. (2020, March 25). Coronavirus and the Politics of Crisis Fatigue. The Conversation.

Mayo, L. (2020). The Postnormal Condition. Journal of Futures Studies, 24(4), 61 – 72.