Sublimity in Everybody's Gone to the Rapture

Video games are a popular form of digital media, delivering interactive stories to generations that pursue ever greater technological immersion. Games have seen a further rise in popularity for those seeking relief from boredom during the coronavirus lockdown measures of 2020 (Sweney, 2020). However, they can offer an aesthetic experience that goes beyond simply a cure for boredom. Games provide many visual, auditory, and interactive opportunities to engage players in experiences that can shock and exalt them and invite them to consider their own limitations. This is true of the walking simulation adventure game Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture (2015). Through consideration of the narrative and game mechanics I aim to prove that the game delivers an experience that could be considered sublime.

The Sublime

The sublime is a concept that defies a straightforward definition, having been so widely debated and altered over the centuries by thinkers in the fields of philosophy and aesthetics. However, there are threads connecting most definitions that place the sublime as an experience or state of mind in which we are affected by something that is too great for us to process or comprehend. According to Shaw (2006), the sublime is an experience consisting of “painful pleasures” that make us feel “simultaneously diminished and enlarged” (p. 3).

For Edmund Burke, the painful aspects of the sublime arise from feelings of terror (Shaw, 2006). It is perhaps due to this emphasis on terror that the sublime is frequently linked to thoughts of death. Burke claimed that “to make any thing very terrible…obscurity in general seems to be necessary” (quoted in Shaw, 2006: p. 70). This suggests it is the unknown that terrifies us; objects, events, or ideas that we cannot clearly perceive or understand. In this way, death is perhaps the most terrifying concept of all because it is impossible to know. Burke suggests that the sublime is related to “the impulse to sustain oneself in the face of danger… so long as actual danger is kept at bay” (quoted in Shaw, 2006:p. 74). Lyotard’s (1993) theories further support the importance of distance from the threat, because the safety provided by such distance “provokes a kind of pleasure that is…relief” (p. 11). Therefore, experiences in which we are able to contemplate death and/or danger can be sublime because they combine the terror of the threat with aesthetic contemplation and the pleasure of overcoming it.

Eagleton (2005) builds on this to suggest that we can experience the sublime through observing others in peril. He purports that, “we revel sadistically in the calamities of others” (p. 34), and so receive a sadistic pleasure from seeing terrible things happen to other people. Eagleton highlights the sublimity of God as a “violent void”, which in a secular society is paralleled by the “otherness at the core of our being, for which another name is desire” ( p. 32). According to Eagleton, they are both, “cruelly indifferent to our wellbeing” (p.32) the realisation of which gives way to feelings of nothingness and meaningless existence that are painfully sublime.

Ideas of sublimity are often entangled with those of beauty, both being aspects of aesthetics that lift us up in some way. However, Shaw (2006) explains that, “the sublime is greater than the beautiful” (p. 12), the former embodying darkness and intensity, whereas the latter is considered lighter and in line with social tastes. Although it may be there are aspects of beauty within the terror of the sublimeand that the pleasurable aspects of a sublime object, event or experience is described as beautiful.

Everybody's Gone to the Rapture

Figure 1: Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture (2015)

Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture (2015) is a story-rich, walking simulator game in which the player explores an English village whose inhabitants have vanished. The game is split into chapters based on the lives of some of the former residents: Jeremy, Wendy, Frank, Lizzie, Stephen and Kate. A guide in the form of a ball of light is provided for each chapter, indicating to the player possible routes they can take through the village.

The player has little interaction with their surroundings, with the exception of a slightly more complex mechanic for accessing key story scenes. Over the course of the game, these story scenes are unlocked and combined with information from old radio broadcasts and telephone conversation logs to reveal what took place in the weeks leading up to “the event” that caused the entire community to disappear.

The player learns in varying amounts of detail , that a mysterious sickness originating from scientific experimentation in the observatory spread through the village. The village was quarantined, cut off from the rest of the world, and eradicated by nerve gas delivered through an airstrike to protect humanity. The player begins their exploration of the village after these events take place, the story scenes act as flashbacks.

Beauty & Threat

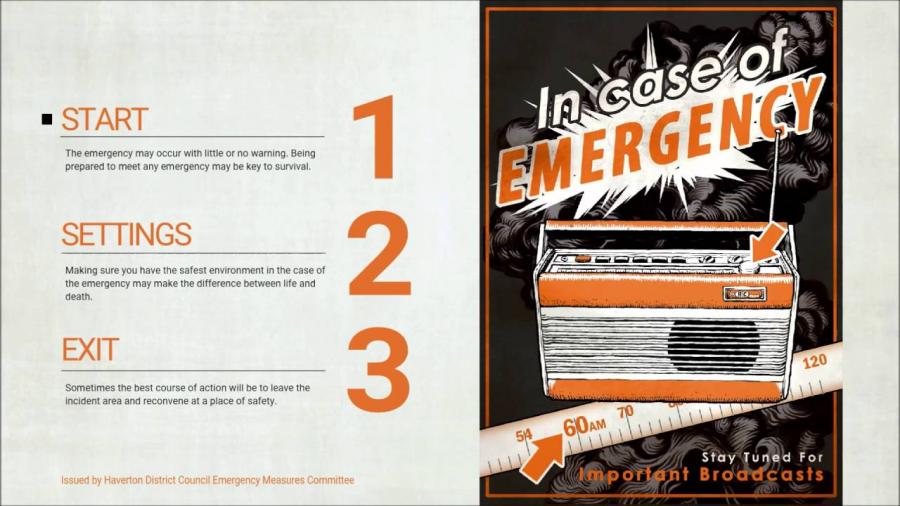

From the very beginning of the game the player is immersed in a beautiful, picturesque English village, with an ongoing sensation of imminent threat. The first menu screen displayed prior to launching the game is formatted as a flyer that urges caution.

Everybody's Gone to the Rapture Menu Screen

The flyer states that “the emergency may occur with little or no warning”. This immediately instils a feeling of threat and leaves the player unsure of their role in the game. It is unclear whether the danger is in the past or ongoing, creating a lingering feeling of unease.

In the transition from the menu to the gameplay, there is an audio clip of a distressed female voice saying, “it’s all over…I’m the only one left”. This is then immediately juxtaposed with the visual presentation of the stunning scenery. The graphics begin as a monochrome drawing of a sunrise over a field and flowerbed, with leaves falling from the trees. Colour gradually seeps into the image before it is rendered more realistically and the player gains control of the camera and is able to move. The beautiful visuals in the game are consistently interrupted with disturbing symbols, such as cobbled roads lined with flowerbeds and the presence of vibrant butterflies and dead birds underfoot that the player must walk through. The contrast of this intense beauty with the feeling of threat creates the push and pull of pain and pleasure that exists throughout the game.

Futility of Human Life

Firstly, the game evokes sublime feelings of the futility of human existence, is through the building of complex characters with rich backstories. The player comes to learn of the struggles each character endured in their very normal, human lives, only to see them eradicated and their problems reduced to nothing in the grand scheme of life and death. One of the main story arcs involves Stephen and Lizzie, childhood sweethearts whoresume their relationship illicitly when Stephen moves back to the village with his new wife Kate. The story unfolds in pieces, showing the involvement of and effect on many different characters including Stephen’s mother ,Wendy. This invests the player with a sense of the gravity of the situation. The player learns of Wendy’s sour relationship with her brother Frank, and Frank’s struggle to take care of himself after the death of his wife. Every character is living a full and complex life, which is ultimately stopped in its tracks and reduced to nothing by the event. This forces the player to contemplate the inferiority of human existence in the face of death.

Chaos and the Rhizome

The mechanics and structure of the game contribute to a sense of overwhelm feelings for the player. The open-world aspect of the game means they can wander freely across the map, encountering snippets of story as they stumble upon them. Some of the roads lead in circles, others bypass areas of the map completely. This means that it can be easy to miss some areas and therefore miss story scenes and pieces of the puzzle. The game requires some pivotal scenes to be witnessed before allowing a player to reach the closing scenes of each chapter, but many can be undiscovered leaving the player to continue the game without the whole story. Due to this freedom of exploration and the overlap of events between chapters and perspectives, the story is not told in chronological order. The structure of the narrative is rhizomatic rather than linear.

A rhizome is a structural concept identified by Deleuze, in which there is no defined beginning or end, or singular path between points. “Any point of a rhizome can be connected to anything other” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987, pg. 7), and the lack of a set path or clear meaning can be disorientating. Warren Sack (2007) notes the “convergence between Deleuze’s work and the scientific theories of complexity and chaos” (p. 204), and it is the chaotic nature of the rhizome that can leave anyone exploring it potentially lost or overwhelmed. The rhizomatic structure employed in Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture contributes to a sublime experience for the player, who struggles to piece together a linear narrative from a mass of connected story snippets.

Religious Sublime

The game utilises religious connotations to evoke sublime feelings in the player. This is evident in the use of the word 'rapture' in the title, which itself has religious and sublime connotations. The Merriam Webster dictionary defines rapture as both, “a state or experience of being carried away by overwhelming emotion” and “the final assumption of Christians into heaven during the end-time” (Merriam-Webster, n.d.). Originally the sublime was closely related to feelings of religious or spiritual transcendence, and many people think of the biblical apocalypse as the epitome of a sublime experience (Shaw, 2006, p. 2). Through use of the word ‘rapture’ to describe the disappearance of the people in the game, the player is invited to feel a sense of awe akin to that of witnessing a religious experience that might be considered sublime.

This is built upon by the very first chapter of the game. In this chapter players are introduced to alight guide called Jeremy, who learn is the pastor of the local church. Playerswitness his interactions with other villagers and his calm and loving approach to dealing with their rising panic. As this is the first chapter, it means that the first time a player experiences the event it appears to take place within the church. At the time of the event or rapture, Jeremy is crying alone in the empty church, reciting a psalm through his tears. As he speaks, an angelic voice sing his words back to him like an echo. Eventually he is interrupted by sounds of interference and a soft roaring. The light that has been indicating where Jeremy stands then forms into the shape of a body more clearly for a moment before fading away. This gives the illusion of his body being taken into the light, which is a common metaphor for ascension to heaven in religious texts. Further, this use of religion plays into the concept of Eagleton’s indifferent “other” (Eagleton, 2005). In the walk leading up to Jeremy’s final scene, he loses his composure and shouts, “Are you there? Can you hear me - are you out there, you bastard? You got them all”. The suffering and death Jeremy has witnessed up until this point is a test of faith, leading to the equally devastating possibilities that God either does not exist or is indifferent to the suffering of humans. The player too experiences the concept of God as Eagleton’s (2005) “violent void” (p. 32).

Jeremy in the church, ascending at the time of the event/rapture

The narrative of the game highlights the unjustness of life, which contributes to the idea that God is absent or indifferent. This is particularly evident in the narrative arcs for Lizzie and Rachel. Lizzie, now pregnant with Stephen’s child, is left waiting at the train station where Stephen promised he would meet her to escape the worrying sickness. When he does not arrive, she calls him from the platform, assuming he has chosen to stay with Kate and telling him she cannot wait. She laments how she, “should have left long ago” but then is distracted by the sound of the air strike, innocently proclaiming “oh, there’s the planes”, presumably on the assumption it is a rescue. Lizzie was deprived of her chance to leave. Depending on how much of the story has been unlocked, the player may now have witnessed that Lizzie had endured an abusive, alcoholic husband, permanent disability following an accident, and subsequent relegation to the other woman of her childhood sweetheart. Lizzie had endured a difficult lifeand a tragic end. This is echoed in Rachel’s narrative, who is a teenager keen to build a life away from the village. She takes on the responsibility of caring for a baby after its parents disappear, something that keeps her bound to the village past the point of escape. In what is likely the final meeting with her boyfriend he tells her, “Spain can wait.” He leaves to check on her parents, hinting at the future they planned together will never be. Rachel’s caring nature does not save her, which may cause the player to contemplate the chaotic and senseless nature of life and death.

That the player witnesses each of the main characters at the time of the event, which is the time of their death, can be considered sublime as a form of schadenfreude. The goal of the game is to understand more about the death of an entire community, which is a macabre concept in itself. Games are designed to entertain, and people who choose to play a game which makes it clear there will be presentations of suffering are choosing to engage with tragedy to be entertained by it in some way. Players are drawn in by, “that strange inward glow of satisfaction which we experience when disaster strikes our neighbour” (Eagleton, 2005, p. 34). Therefore, the feelings of “pity and pleasure” (p. 34) evoked by watching the characters die is sublime.

Music as a Vehicle for Sublimity

Finally, Music is aused artfully in the game to add to the sublime experience. The soundtrack is comprised of live orchestra recordings with choir vocals, which feed into the religious undertones of the game. The composer, Jessica Curry, explained that she intended to capture a, “sense of nostalgia for a world that is already gone” (Curry, 2017).The music casts a melancholy shadow on the player as they wander around the beautifully rendered countryside. As with Jeremy’s ending scene, the vocals in the music often echo the words of the characters, which give the impression of immortalising their words and lending them a greater gravity in death. In Rachel’s final scene she is comforting the orphaned baby with a rhyme that is sung back to her by the choir as a tragic lullaby:

“Sleeping baby, shadowed dust

Clouds and starlight, starlight, starlight

When we're called to go we must

Into starlight, sleep and love”

Here death is described in gentle terms, as a source of comfort to the innocent as tragedy befalls them. It encourages the player to think about the unjustness of death against the fragility of human life. Every main character in the game has their own musical theme that plays at the beginning of their chapter and is sometimes reprised when they appear in the chapters of others. For each the lyrics refer to death in poetic terms and related to that characters experience of death. Wendy lost her husband in the war, and her theme includes the lyrics:

“In their song, I heard your song

I heard the bomber's drone

Beneath those birds and the swaying wheat

I heard you coming home”.

In Wendy’s ending scene, she becomes excited at the sound of the planes coming in for the airstrike and exclaims that it is her husband finally coming home. That Wendy can feel the love in death – that she can hear her husband’s song in the song of the planes - is both heart-warming and tragic; once again providing the painful pleasure of the sublime.

Implications of the Sublime Video Game Experience

Through analysis of the narrative and gameplay of Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture (2015), it is clear that the game is capable of delivering an experience to the player that could be considered sublime. The player is forced to confront ideas of the futility of human life, the unknowable quality of death, and the destructive and indifferent power of the “other”. It allows the player to derive pleasure in the misfortune of the doomed residents, following the details of their disintegrating civility and eventual demise. That the player experiences these feelings in response to events taking place in a fictional world on their computer screen provides a distance from any real threat. This distance allows for aesthetic contemplation of such existential and largely incomprehensible topicsthus, video games lend themselves well to creating such a sublime experience.

Further research into sublimity in video games might consider potential uses in activism. Salmose (2018) discussed the potential for activism within climate change disaster films. Given the added interactive aspect within video game narratives, games may be an appropriate media for instilling a sense of urgency and action in the public through the use of the sublime in a narrative relating to climate change.

References

Curry, J. (2017, April 21). Jessica Curry: The Indie Video Games Music Composer (A. Morris & S. Pinot, Interviewers).

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. 1987. A thousand plateaus: capitalism and schizophrenia, London: Athlone Press.

Eagleton, T. (2005). Holy Terror. Oxford University Press.

Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture (PC Version) [Video Game]. (2015). Brighton, UK: The Chinese Room.

Lyotard, J.F., Bennington, G., & Bowlby, R. (1993). The inhuman: Reflections on time. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Rapture. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

Sack, W. (2007). Network Aesthetics. In V.Vesna (Ed.), Database Aesthetics: Art in the Age of Information Overflow (pp. 183-210). University of Minnesota Press.

Salmose, N. (2018). The Apocalyptic Sublime: Anthropocene Representation and Environmental Agency in Hollywood Action-Adventure Cli-Fi Films. The Journal of Popular Culture, 51(6).

Shaw, P. (2006). The Sublime. Psychology Press.

Sweney, M. (2020, December 21). UK video game industry thrives amid lockdowns and US bidding wars. The Guardian.