The Suspicious Comeback of FMV Games

Full Motion Video (FMV) games, which were popular in the early and mid-nineties but then became outdated, are making a surprising comeback with titles like Her Story and The Infectious Madness of Dr. Dekker. These games are populated by unreliable narrators, and their conspiratorial narratives and lack of editing invite a suspicious and paranoid player attitude. The lack of interactivity the genre is often derided for by the gaming community, is precisely its strength, through which this new generation of FMV games challenges players’ analytical and hermeneutic abilities and trains their cognitive patience.

What are FMV Games?

In the early 1990s, full motion video was a novelty in games. Its creation was enabled by the increase of memory on carriers like the CD-ROM, which, with roughly 650 megabytes, encouraged the use of better graphics, better sound, and even integrated video clips. Advances in computer animation meant more photorealistic graphics, and full-motion video began appearing in games. The 7th Guest (Trilobyte, 1992), over a gigabyte in size, was the first CD-ROM game to require two discs. The Sega Saturn and the Sony PlayStation, launched in 1995 in the US, brought the technical abilities to integrate quality FMV with better visuals in CD games (Wolf 2008).

Night Trap (1992)

FMV games had their moment of niche popularity during the early and mid-nineties with titles like Mad Dog McCree (1990) and Night Trap (1992). The primacy of CD-ROM technology in these years benefited slow-paced genres with relatively simple gameplay mechanics. Often, this involved voyeurism, especially spying on scantily clad women (Night Trap; Voyeur (1993); Tender Loving Care (1998)). However, due to their lack of interactivity, such games were unable to withstand the competition with established franchises and gameplay innovations of that time. The decline of Sega further led to the genre‘s obsolescence.

Since a couple of years, we are seeing a surprising revival of this style of game making. To mention a few: Baggy Cat’s Contradiction: Spot the Liar! (2015), Sam Barlow’s Her Story (2015) and Telling Lies (2019), Splendy Games’ The Bunker (2016), and D’Avekki Studios’ The Infectious Madness of Dr Dekker (2017), The Shapeshifting Detective (2018), and Dark Nights with Poe and Munroe (2020).

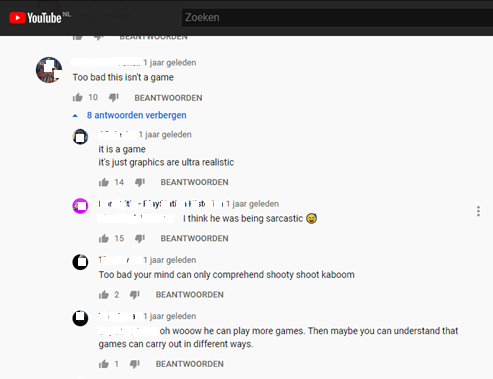

“It’s not a game”

Just as their nineties predecessors, these titles are low on interactive affordances. Most of the playing ‘action’ consist of passive acts of listening, watching, waiting, and paying attention while actors speak in front of a camera. Like environmental story-games such as Gone Home and Dear Esther (pejoratively called ‘walking sims’), they reject the traditional mechanics of first-person experience by denying the player some of her agency (Bogost 2016). The ‘player agency’ (Koenitz 2018), or impact of the player on the narrative, in these games is closer to a novel or film. It has become somewhat of a running gag on YouTube and Twitch to leave the comment ‘It’s not a game’ under videos devoted to the genre (see Juul 2019).

Youtube Comments to trailer for The Infectious Madness of Dr. Dekker

What is it about these quirky, nostalgic, and slightly awkward games, with their overacting performances and retro materiality, that speaks to us in a time in which gaming technologies are so much more developed than they were in the mid-nineties, when the genre was already passé? I think their lack of interactivity might actually work in their favor. In 1987, Peter Rabinowitz compiled what he called the ‘rules of notice’ by which the details in a narrative are hierarchically organized in such a way that a reader knows on what elements to focus. Certain elements are ‘foregrounded’, causing heightened attention, and others are ‘backgrounded’, nudging the reader to read them in a more superficial manner. Unlike more traditional narratives (like short stories or detective novels), FMV games withhold their rules of notice, as part of their procedural rhetoric: this concept denotes the arguments a game makes ‘through the authorship of rules of behaviour, the construction of dynamic models’ (Bogost 2010, 29). Here, the procedural rhetoric lies in an unwillingness to instruct the player as to what is important.

Her Story

Her Story (2015) by Sam Barlow, an interactive movie game for Windows, Mac, iOS and Android, is not interactive in the narrow cause-and-effect sense of a branching narrative where a player’s choices determine the events. Rather than a ‘choose your own adventure’ story, the player is here presented with just one story, and only agency in how to build it up. Technically, all that happens in the game itself can be summed up by ‘clips are played’: the rest happens in the player’s imagination.

As a player, you sit down at an antiquated computer desktop, featuring a 3.1-style Minesweeper-like game. A ReadMe file explains the computer’s mechanics. There is a so called "L.O.G.I.C. Database" with 271 video clips. The interface displays an aesthetic of hypermediacy, a layering of different windows and applications that compete for our attention. It makes the viewer accutely aware of the mediated nature of what she sees. An example of the ‘independent style’ (Juul 2019) in videogames, through its archival footage and outdated interface, the work evokes an older, analogue materiality. Its full motion video has been filtered with the effects of analogue VHS. This nostalgia for older forms of entertainment is part of the reason for the genre's popularity. This adds to its reality effects, as the story is set in 1994.

Her Story (2015), interface

You browse this database of clips from fictional police interviews to solve the case of a missing man whose murdered body is later discovered. The interviews are all with his girlfriend Hannah Smith, played by the British musician Viva Seifert. The game has no explicit mechanical objectives and there is no index of player progress. In the search bar, a single word is loaded up: ‘MURDER’. Hannah’s answers have been transcribed, and you find fragments by entering words in the search bar. Sorting can be done by inventing user tags, which are then available as searchable items. You can use the search bar in different ways. The police context and ‘MURDER’ prompt indicates the direction the narrative will take. At the same time, you can choose to search for seemingly random words and get a feel of the characters first before inevitably being pulled into the plot.

Why does Hannah have a tattoo in some clips that seems to be missing in others, a bruise that seems to disappear and reappear? Why does she request black coffee instead of tea?

In any case, searching for specific words does not mean you’ll find what you expect to find. In teasing out the plot, you have to pay attention to both verbal and visual clues to get to know the character better. Why does Hannah have a tattoo in some clips that seems to be missing in others, a bruise that seems to disappear and reappear? Why does she request black coffee instead of tea at some point? Are all clips of the same woman, are we looking at twins, does she suffer from split personality?

And while we're at it, who are you as a player, and why are you investigating this cold case? Every now and then, during moments of tension in the clips, lights flicker, providing a glimpse of ‘your’ face looking into the old CRT monitor. You are also confronted with your own assumptions and frames through mysearch record, another reflection. When I all too readily hypothesized someone might’ve had an affair, Hannah reproached me: ‘You’re reaching here. Why are you so obsessed with sex and affairs?’

The procedural game lacks closure. It does not tell you if and when you are finished: at one point, which seems randomly assigned to different playthroughs, a chat window pops up and you are asked whether you think you understood. If so, you can leave the station. Her Story is dialogic (even if one half of the dialogue takes place in the player's mind) and asks you to practice empathic engagement as you imagine this woman’s motivations. It is, in other words, an exercise of the imagination. You are a player rather than a gamer, if '[g]ames have results: they define a winner and a loser; play does not' (Frasca 1999). You don't play to get a high score; there are no cheats; it is not a puzzle. It is about inference, listening, and understanding. It's a game of construction and editing that as a player you supply yourself. Consequently, there is no palpable or quantifiable result, just the possibility of understanding.

Telling Lies

Telling Lies is based on the same mechanics, only it offers more of everything: more characters, more sources of information, more storylines, and more affordances for navigation. You’re sitting behind a laptop in what is probably a private study. No explicit instructions or mechanics are given, other than the word “LOVE” typed into the search box (like MURDER, a nice prompt for narrativity). Again, you don't know what you’re looking for or why, and who you even are. When you enter key words, five clips are randomly selected for your viewing. You can replay them, slow them down or speed them up, and select keywords in the transcripts to base your next search on.

Like in Her Story, there is no editing within the clips. Editing normally functions as a tool for guiding the viewer’s attention towards important plot elements. Here, the player is on their own. We see the images through a webcam in a simulation of a video call, or sometimes a stationary hidden surveillance cam, so there is no camera direction or conventional framing. This means that every little gesture or detail could be a clue.

Telling Lies (2019), still from a clip with Ava

The majority of videos you retrieve are of one side of a dialogue captured by a webcam; somewhere, there's a separate video file containing the other half. With these decontextualized snippets of interactions, you are primed to be maximally vigilant with respect to possible intentions of the speaker. You don’t know who’s talking on the other side; you only see the minimal facial responses of the listening party and get the chance to really scrutinize them. One person's silence when the other speaks can take a while. That counterpart you often find much later so you’ll have to observe, remember, and suture them together in your mind. Tellingly, you can play a game of Patience on the desktop interface. The deck is one king short, which might foreshadow something about the game as a whole: better have infinite patience, for the puzzle will never be complete, and you cannot win.

Soon, you’ll figure out that all videos have one interlocutor in common: one David Smith (Logan Marshall-Green), undercover FBI agent. His mission is to investigate Green Storm, a radical (terrorist?) environmental organization that plans to blow up a bridge to stall construction of a pipeline which would feed oil into the local Native American environments and poison their water sources. He has left his wife Emma and kid Alba at home, falls in love with activist Ava, and somehow still finds the time to naively share all his secrets with a cam girl named Max. An alleged terrorist activist group, an affair, infiltration, blackmail, code names… the game has it all.

I tried to go straight for the action, but you have to go through the flirtations with the cam girl, the domestic fights, the lovey dovey stuff

Sometimes, David is watching his girlfriend Ava for minutes on end, or looking at his daughter falling asleep. This helps humanize him, although his behavior becomes increasingly erratic. The acting is realistic (this is a difference between Barlow's and D'Avekki Studios' productions). The game is voyeuristic, reminiscent of the old FMV games. There is suggested webcam sex, with wife and girlfriend but not the cam girl, with whom David just wants to talk: ‘Now I want you to tell me a story you’ve never told anyone before’. As said, you can accelerate the often long and testing clips, but there’s the chance of missing something. You have to endure ten minutes of baby talk, but then the mom comes into the room and a potentially significant discussion ensues. When I played it, I tried to go straight for the action, entering search terms that seemed to be central to the conspiracy like Prosperen, Green Storm, A-squared, code names like Sleepy and Dopey. But the game will not let you off the hook: in order to fully understand the story and exit the database, you have to go through the flirtations with the cam girl, the domestic fights with his wife and the lovey dovey stuff with Ava. You lack the agency to decide for yourself when you’ve seen enough.

Telling Lies (2019), interface

On a couple of occasions, you’re abruptly taken out of the (intra)diegesis (the storyworld), and the interface reveals another diegetic level: off-screen, 'your' partner comes in and asks if you’ll come to bed, it’s 4AM. At that point, I had indeed been playing clips for some hours and my room had gotten dark. Engaged in the hermeneutic activities of searching, watching, and trying to make sense of it all, you converge with your character, of whom you only see a vague (blond, female) reflection on the screen: as a player, you are literally doing what she’s doing, which creates an interesting mode of immersion. Another time, 'your' cat jumps on your keyboard, which is startling: you tend to jump up, just as your character does.

David’s daughter Alba asks, after he reads to her the fairytale of Rumpelstiltskin (another story about secrets and lies): ‘At school we had to write the author’s message for every story. Was Rumpelstiltskin the bad guy?’ This applies to her father, who might be well underway of becoming ‘the bad guy’ in his own story. That David (code name: 'Prince Charming') is a master manipulator is not to say that the other characters are honest. Cam girl is not who she says she is: the name 'Max' on her tattoo is not her criminal ex-boyfriend like she says, it's her; she slips in and out of accents, wigs, and attitudes. She hides her identity to survive, to protect herself from men like David. Your own identity as a player isn’t revealed until the end, after having seen David fulfill his mission, although it’s no way near as impactful as the resolution of Her Story (I won't spoil either for you here).

The Infectious Madness of Doctor Dekker

D’Avekki Studios’ The Infectious Madness of Dr Dekker (2017) is marketed as ‘A Lovecraftian murder mystery FMV game with a dash of Cthulhu’. At the beginning, you learn psychiatrist Dr. Dekker has died, and you are hired as his replacement. What looks like suicide, soon is called into question: it is suggested he’s been murdered by one of his patients or his secretary Jaya. You investigate his death by talking to his patients: ‘He was a good listener. I hope you are’. This comes down to picking certain key words out of their responses and repeating these in the form of a question (among the Hints: ‘A new study in Psychology Yesterday suggests using the same words as your patients increases trust’). Players input text to ask the patients questions (or if you are lazy, you can choose between pre-formed options). This parotting gets monotonous and I didn't find all stories terribly interesting (the siren and 'angel of death' threads were quite captivating; the gravedigger was feeling way too sorry for himself).

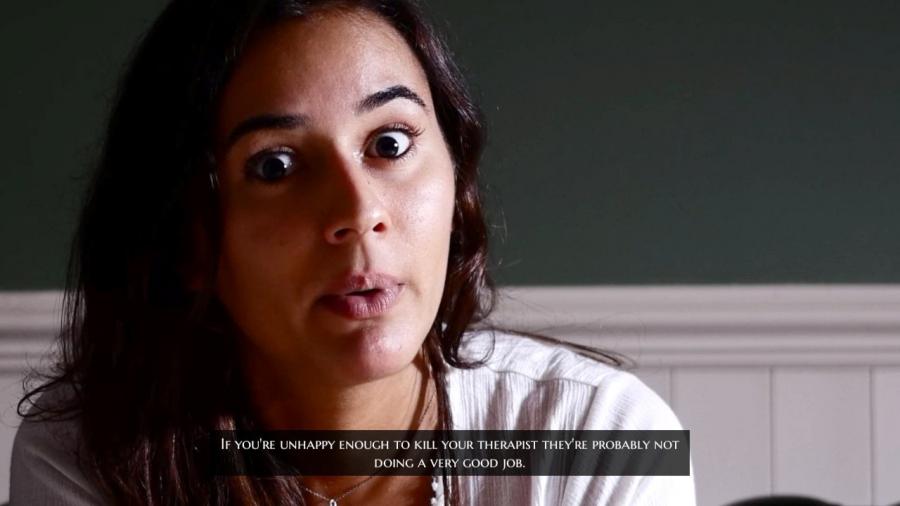

The Infectious Madness of Dr. Dekker (2017), Jaya

All conversations, hence the gameplay, take place in a single room (In FMV games, there is often little or no environment to explore): a typical psychiatrist’s office with a green wall and a leather couch; Rorschach tests are displayed on the wall behind the patient. The lighting is low-key, giving off a sinister vibe with high contrast. The performers are relatively unknown and don’t look like typical Hollywood actors, more like normal people with every little flaw brought sharply into view. This would contribute to authenticity, were it not for the overall nightmarish aesthetic and slight overacting. The atmosphere is pleasantly ‘off’, exaggerated, and quirky.

Elin is an ‘angel of death’, a nurse who shapeshifts into patients’ loved ones before they die so they can say their goodbyes (and she gets their belongings). Maryanna is a siren, people watch her dance and get hypnotized, they follow her to the beach and to the bottom of the ocean where they are devoured by something evil (‘I follow the glow like they follow me’). Bryce is a gravedigger who has an extra hour in his day in which he does all sorts of cheeky things. Nathan is stuck in time after losing his girlfriend in an accident, he has ‘leap days’ like in Groundhog Day. Claire managed to kill and then (poorly) resurrect her husband.

Unsurprisingly, they prove an untrustworthy bunch. You catch them out on fibs and inconsistencies (‘My favorite nightclub sells cheap vodka shots'; 'I don’t drink'). The camera work is interspersed with jarring zooms on restless hands in laps and other details of neurotic, guilty behavior. The game offers a paranoid experience; attention can go over into insanity. Everyone is lying: one character because they are trying to be declared temporarily insane; the others because they are deluded... or not?

Each new chapter starts with a montage of fragmentary flashbacks from past conversations, with patients’ faces weirdly distorted and the images unsteady, like you are slowly losing your grip on ‘reality’. When you are not asking questions, the patients flicker eerily in and out of view, waiting, fidgeting, pacing back and forth. It is as if they are there and not there, figments of your imagination. You clearly cannot trust anyone, including your own perceptions. You see a patient holding a flame in his hands, a glass disappearing, a creepy little girl emerging on the couch out of nowhere for just a few second. Patients start expressing concern: you look pale, are you okay? You are apparently living in Dekker’s house. Are you becoming him?

The Infectious Madness of Dr. Dekker (2017), Claire

I chose to play along with whatever my patients told me, telling Elin for instance it is not wrong to keep her patients’ gifts after they die while believing she is their close relative, or flirting with Maryanna: ‘Do you think my hair is pretty, Doctor?’; ‘Don’t you think I’m sweet Doctor’? (Definite Laura Palmer / Dr Jacoby vibes here). When Bryce asks ‘What would you do [if you had an extra hour]?’, I answer ‘spy on people’, ignoring the morally correct alternative ‘help people' in the hopes of eliciting a confession. It works: predictably, Bryce used his powers to break into women’s houses, take off their clothes and take pictures to look at later. When I took the playing along strategy too far, my patients got suspicious.

Bryce claims that ‘Dr Dekker made me this way’; the psychiatrist stimulated his patients to ‘use their imagination’. Jaya the secretary helpfully suggests you should find patterns in patients, a common experience. Later she all but gives it away by mentioning the book The Cult of the Kinetic Mind, which describes how cult leaders turn followers into disciples by making them see anything and then believe it. Dekker actively recruited patients with psychokinetic powers, the ability to change the physical world, using ones mind. He tried to make them ‘think things’ and then make these things ‘real’. He demonstrated several patients how he could jam a spike through his hand with no pain, and be healed the next second. He called this magic. There are roughly three player strategies: play a benevolent psychiatrist and cure your patients by showing them their powers are delusions, follow Dekker in convincing them they have kinetic powers, or go so far in convincing them that you start to believe them as well.

You can unlock multiple endings and there are several side quests to complete. The outcome varies, as the murderer is chosen randomly at the beginning of each game. Different ‘insanity’ outcomes range from giving the killer the insanity plea they are after (so the killer wins), to becoming the new Dr. Dekker and getting killed yourself, to losing your sanity altogether, infecting others with your 'madness' and being locked up in a psychiatric ward. These outcomes are based on how outrageous your suggestions to the patients are. Because of the randomization of the killer and the relative randomness of the outcome, the plot of the game is rather unimportant. There is a certain pleasure in experiencing narrative worlds in such a mode of ‘paranoid reality’ that this game exploits very well. What starts out with a conscious choice to see reality a certain way might end with actually believing what you see.

It’s not a movie either

Considered in light of the current state of the art of video game technology, the FMV genre is extremely limited. The reason why film is traditionally thought to sit uneasy with games, and a bit of an embarrassment, is simple: when you’re playing, you’re not watching and vice versa. Bogost went as far to say that video games are 'better without stories’. Games tell their stories in a different manner, by approaching everyday objects in novel ways.

And yet, whatever you call them, games or no games, these new FMV games would not ‘work’ as a movie. Even when you’re excluded from the diegesis, as a player you are vital in supplying media literacy and using your imagination to ‘edit’ the images, to decode them, suture them together in an attempt to understand people we’d with right call problematic. Because you are (suggestively) embodied or instantiated in a narrative layer, you feel more responsibility for the story (a movie will also end if you fall asleep halfway through). Yet, because there is not much you can actually do or control, you just watch, listen, be patient.

Because there are no 'rules of notice', that authors of narrative fiction use to guide the reader's attention, and no editing as used by filmmakers to do the same things, anything can be important. An active, vigilant attitude is expected of the player, but not in the sense of interactivity expected of the gamer: everything happens in the player's imagination. There is always the chance that something vital is missed, that we have not fully understood a situation, which makes such works typical for our experiences in an information age. The FMV game with its media specific characteristics of maximum extension and minimal interactivity, actually found its new niche in a time when we often use media for exposure and self-expression, when we block and unfollow anyone we might disagree with.... but rarely just attend.

References

Bogost, Ian. Persuasive games: The expressive power of videogames. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010.

Bogost, Ian. Play Anything. The Pleasure of Limits, the Uses of Boredom, and the Secret of Games. New York: Basic Books, 2016.

Frasca, Gonzalo . “Ludology Meets Narratology: Similitudes and Differences between (Video) Games and Narrative” (1999). Web.

Juul, Jesper. Handmade Pixels. Independent Video Games and the Quest for Authenticity. Boston, MIT Press, 2019.

Koenitz, Hartmut. “What Game Narrative Are We Talking About? An Ontological Mapping of the Foundational Canon of Interactive Narrative Forms.” Arts 7.51, 2018. 1-11.

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA, and London: The MIT Press, 2001.

Rabinowitz, Peter. Before Reading. Narrative Conventions and the Politics of Interpretation. Ohio State UP, 1987.

Wolf, Mark J.P. ‘Chapter 15: Genre Profile: Adventure Games.’ The Video Game Explosion. A History from Pong to Playstation and Beyond. Ed. Mark J.P. Wolf. Wesport & London: Greenwood Pres, 2008. 81-88.